You are 40,000 feet in the air, flying across the Atlantic Ocean when the intercom crackles to life and you hear the words you’ve dreaded ever since graduating medical school: “Is there a doctor on board?”

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 41 – No 12 – December 2022After showing the flight attendant your credentials, you meet the passenger: a 53-year-old man with difficulty breathing and a rash. The patient is audibly wheezing. The flight attendant hands you a medical bag, but you can’t hear anything with the disposable stethoscope over the turbulence. The rash on his arms and chest appears to be urticaria, and his tongue and lips are mildly swollen. Anaphylaxis, you decide, but what can you do? You peer skeptically at the emergency medical kit, which suddenly seems much smaller than you want. What medicines are even in there?

The Situation

In-flight emergencies occur in about one in 604 flights, with complaints most commonly ranging from syncope (37 percent of in-flight emergencies) to respiratory issues (12 percent), vomiting (six percent), and cardiac complaints (eight percent).1,2 When an emergency physician or nurse isn’t available, flight staff are trained in basic life support and can often avail themselves of an on-the-ground medical communications center with real-time advice.1,2,3 Whether or not on-board medical help is available, one in 14 flights with medical emergencies is diverted from their original destination to the nearest airport in the vicinity of appropriate medical facilities.1,2

The Emergency Medical Kit

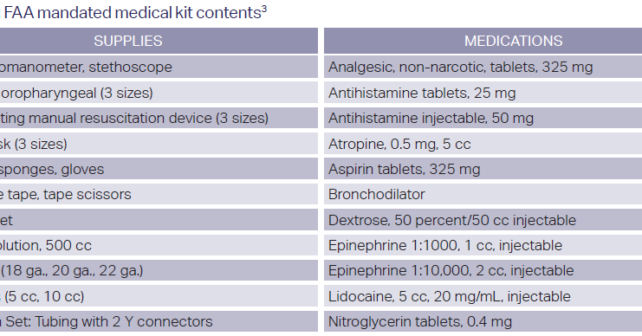

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) requires every major commercial airplane to carry an Automated External Defibrillator (AED) and a standard medical kit (see Table 1).3 The guidelines for this medical kit have not been updated since 2006, though in 2019 the Aerospace Medical Association was tasked by the FAA with producing a list of recommended (though not required) updates (see Table 2).3,4 Many airlines have chosen to supplement the kit with additional supplies or medicines. While this does provide some much-needed fortification to the core FAA kit, it does result in variation between airlines, so a medical volunteer during an in-flight emergency may not be familiar with the available supplies. Of note, FAA exemption number 10690, which has been in effect since 2013 and was recently extended, allows airlines to not immediately update their kits with atropine, dextrose, epinephrine, and/or lidocaine under special shortage considerations.5 This means that medical kits may not always include these lifesaving and previously mandated medications. Similarly, these medications may be expired as there is no strict enforcement on checking expiration dates of medications. When assisting in an in-flight medical emergency and finding yourself short of epinephrine or other medication, it’s worth having the flight attendant ask passengers, as combined they often carry a cornucopia of personal pharmaceuticals or personal medical equipment.

Pages: 1 2 | Single Page

One Response to “How To Prepare for In-Flight Emergencies”

December 18, 2022

Doron Spierer, MDIf the airline gives the Physician a gift (credit, miles, or even a bag of salted cashews) after rendering medical aid to a fellow passenger, could this be construed as compensation, thus jeopardizing Good Samaritan status?