These results were reviewed, and the emergency physician admitted the patient to the hospital. To ensure a telemetry bed for the patient, he entered the hospitalization order under “chest pain.” The hospitalist was contacted, interviewed and examined the patient in person, and admitted him. A cardiology consult was requested, and the cardiologist saw the patient several hours later on the floor. The cardiologist did not feel that this case was cardiac in nature but nonetheless recommended an ECG and a stress test for the following day.

When the hospitalist finished her shift, she signed out to the nurse practitioner (NP) covering the floor overnight. It was the NP’s first day at this job. During the sign-out, the hospitalist and NP received a call from the patient’s nurse that he had become hypotensive and looked unwell. They both immediately went to his bedside. A repeat ECG was ordered and was notable for borderline but suspicious ST-segment changes. Therefore, the hospitalist called the interventional cardiologist (a different cardiologist than who had initially completed the consult), and the patient was taken emergently to the cardiac catheter lab for what was presumed to be an acute coronary syndrome. In the cath lab, a large thoracic aortic aneurysm was discovered. Large hemopericardium was also found. The cardiologist believed that there was an area of fistulization from the aneurysm into the pericardium. An immediate consult with a cardiovascular surgeon was obtained, but the patient went into cardiac arrest shortly thereafter. Resuscitative measures were attempted, but unfortunately, the patient did not survive. The family did not request an autopsy.

The patient’s family subsequently contacted a law firm. After initial review, the family signed a contingency agreement agreeing to pay the law firm 40 percent of any settlement or verdict as well as all litigation expenses. The defendants included the emergency physician, hospitalist, first cardiologist, and hospital. The lawsuit was filed in federal court, as opposed to state courts (which handle most medical malpractice cases). This was done because the patient was from a separate state than the physicians and because the plaintiff’s allegations included an EMTALA violation.

Analysis

One of the primary issues that the plaintiff’s attorney used to support the negligence claim was the discrepancy in documentation about the patient’s chest pain. The triage nurse entered chest pain as the chief complaint, but the physician and nurse both wrote that the patient denied chest pain. The doctor hospitalized the patient on telemetry status due to chest pain, despite writing that he did not have chest pain. These contradictions provide easy fodder for the plaintiff’s attorneys to support their claims of negligence, regardless of whether intermittent chest pain changed initial management (the patient ostensibly received the initial workup that he would have had whether or not he had active chest pain at the time of evaluation).

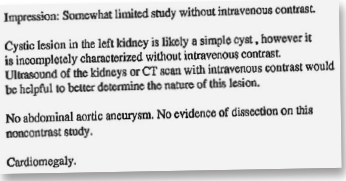

This patient did not receive a chest X-ray despite the conflicting reports of chest pain. To worsen the matter for the defense, the hospital had a written policy for chest pain patients that allowed the ED nurses to order certain tests, including a chest X-ray. The plaintiff suggested that the emergency physician was negligent in his work-up, given that even a simple triage protocol called for an X-ray to be ordered. Additionally, the CT that was ordered in the emergency department was indeed an abdominal CT only and did not include the chest. Therefore, no thoracic imaging was obtained prior to admission.

Both sides eventually agreed to enter into binding arbitration with a neutral party, with a cap on any settlement of $500,000. After reviewing the case, the arbitrator found that the emergency physician and hospitalist were not negligent and that there had been no EMTALA violation. The cardiologist who initially consulted on the patient was found to be negligent (see Figure 3).

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

No Responses to “Inconsistent Records & Insufficient Imaging Complicate Malpractice Case”