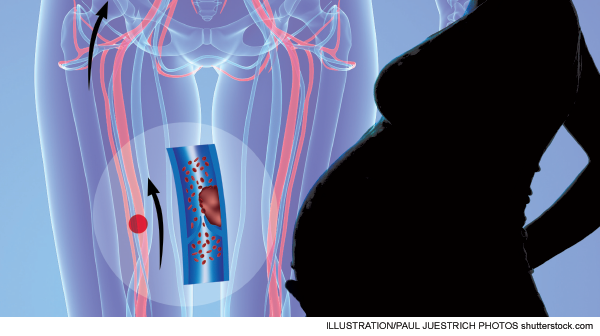

In a more recent cross-sectional study, the incidence of VTE was quoted as 2.5 per 1,000 natural pregnancies and 4.2 per 1,000 pregnancies from in vitro fertilization.3

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 33 – No 02 – February 2014CDRs will lead clinicians to one place in pregnant patients: the wrong answer. Wells is the most validated CDR for deep venous thrombosis but has not been validated in pregnancy.4 Furthermore, neither has the Wells PE rule.4 Physiologic changes that occur in pregnancy alter the physiologic parameters that are often incorporated into VTE CDRs. Edema and leg pain are common in pregnancy. In addition, dyspnea is a common complaint in pregnancy.4 Respiratory rates are also known to increase during pregnancy.

If CDRs can’t put patients in a low-risk category (low pre-test probability), then discussion about D-dimer use in pregnancy should be moot. However, in a desire to reduce radiation exposure in pregnant patients, D-dimer tests are often ordered in this population. D-dimer levels increase throughout pregnancy, beginning in the first trimester, and by 35 weeks, all will be above the cut-off level of 500mcg/L.4 This normal physiologic phenomenon has prompted some investigators to increase the cut-off level for D-dimer in pregnancy. Although false positives clearly occur in pregnancy, it seems to be a flawed strategy to increase the cut-off to avoid false positives at the risk of increasing false negatives. Such changes are under investigation and should be adopted with caution.

If D-dimer is problematic in pregnancy, why not use the PERC rule? PERC is most likely the preferred CDR in current use. However, in the derivation study, six clinical variables were deemed “nonsignificant”: pleuritic chest pain, substernal chest pain, syncope, smoking status, malignancy, and pregnancy or immediate postpartum status.5 Kline and Slattery later reported three factors that were associated with PERC-negative PE. Interestingly, they were pleuritic chest pain, pregnancy, and postpartum status.6 Perhaps removal of these three should be called into question. If nothing else, this certainly limits the PERC rule’s application in pregnancy.

In order to reduce potential radiation exposure, many are recommending that compression ultrasonography be used first in pregnant patients as opposed to computed tomography pulmonary angiogram.4 This approach certainly has merit, particularly in pregnant patients with leg complaints. However, it also has some drawbacks. Venous flow velocity reduces approximately 50 percent in the legs by weeks 25–29 of pregnancy, possibly impacting image interpretation, and isolated iliac vein thrombosis is more common in pregnancy and is difficult to diagnose.1

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

No Responses to “Lack of Data for Evaluating Venothromboembolic Disease In Pregnant Patients Leaves Physicians Looking for Best Approach”