Blunt laryngeal injuries may occur from blunt trauma during fights or sports. Airway obstruction may be immediate or delayed. Unstable patients should have an airway established, generally by tracheostomy or cricothyrotomy. Devascularization and scarring of tissue might result in long-term obstruction. Any intralaryngeal mucosal injury is likely to produce some degree of granulation tissue, which may lead to scarring or obstruction. Prompt repair of the mucosa and avoidance of exposed cartilage is critical. Even with optimal care, patients may become dependent on a tracheostomy and/or gastrostomy in the long term.4

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 42 – No 10 – October 2023Laryngeal injuries may also be classified based on the anatomical site and the structures involved:

- Type 1: Supraglottic: epiglottic hematoma or avulsion; hyoid bone fracture; thyroid cartilage fracture; arytenoid dislocation or degloving; endolaryngeal edema; airway obstruction

- Type 2: Glottic injuries: hoarseness (generally associated with thyroid-cartilage fracture); vocal-cord edema; endolaryngeal lacerations; or avulsion of vocal cords from the anterior commissure

- Type 3: Subglottic injuries: involvement of the cricoid cartilage and trachea with airway compromise; complete cricotracheal disruption with airway obstruction that may be rapidly fatal.7

For completeness, four varieties of laryngeal fracture have been described:

- Supraglottic laryngeal fracture with posterior displacement of the epiglottis and laryngeal inlet

- Cricotracheal separation

- Vertical midline fracture, damaging the anterior commissure and separating the thyroid alae

- Comminuted fracture: more commonly encountered in the older, rigid, and calcified larynx.8

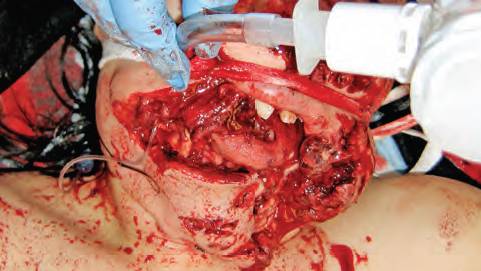

Initial evaluation starts with the history: blunt or penetrating, polytrauma or other injuries, and whether the patient is coherent and cooperative or has an altered voice. Does the patient have difficulty breathing or swallowing? The primary management of laryngeal injuries is to evaluate and establish an airway.

The physical examination, as always, follows airway, breathing, circulation, evaluation of cervical spine. Is the patient stridorous or hoarse? The thyroid cartilage should be checked for prominence or loss thereof. The neck should be palpated for subcutaneous air. Is there respiratory distress or a neck hematoma? Is there an open neck wound or palpable cartilage fracture? The patient should be evaluated for hemoptysis, cough, sternal retractions, thrill, or bruit.

Flexible laryngoscopy, CT scan, direct laryngoscopy under general anesthesia, esophagoscopy, ultrasound, or chest X-ray may all be requested by the surgical consultant. If the airway is deemed to be stable, flexible fiber-optic laryngoscopy and computed tomography of the neck may be appropriate initial studies. Flexible laryngoscopy is used to evaluate mucosal tissues of the larynx and upper digestive tract after the primary and secondary trauma surveys are completed. Edema, laryngeal lacerations, mucosal tears, hematomas, exposed muscle, and vocal-cord paralysis or paresis may be diagnosed in such fashion.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Single Page

No Responses to “Laryngeal Injuries: An Introduction”