The Case

A 58-year-old male presents with worsening lower back pain. He has a history of L4/L5 disc disease and has been seen in this emergency department for this pain previously. Today, he says his back pain is different: It’s more severe and radiates down to both feet, and he notes some difficulty urinating. Could this be cauda equina syndrome (CES)? What should you look for on history and exam? Is there anything you can use to rule out the disease before heading to the MRI machine?

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 39 – No 02 – February 2020Characteristics of CES

We regularly see patients with severe back pain, and we are experts at screening for potentially dangerous conditions. When it comes to back pain, we are on the lookout for pyelonephritis, fracture, spinal epidural abscess/discitis, spinal epidural hematoma, mass, abdominal aortic aneurysm, retroperitoneal hematoma, and CES, as well as a variety of potential abdominal conditions.

If you think that asking back pain patients about urinary incontinence is enough, you’re going to run into trouble eventually.

The cauda equina (Latin for “horse’s tail”) is made up of the ascending and descending nerve roots from L2 to the coccygeal segments. It is responsible for lower limb movement and sensation, bladder control/urination, external anal sphincter control and defecation, sexual function, and sensation of the genitalia and perineal region.1–6 As you may have noticed, these play a huge role in our activities of daily living.

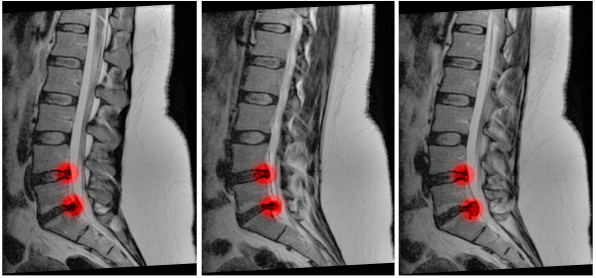

Any impingement or damage to these nerve roots may result in CES. While CES is most commonly due to central disc herniation or prolapse (usually in the setting of prior spinal disease), many conditions are associated with CES including chemotherapy, infection, radiation, vascular lesions, ischemia, trauma, epidural analgesia, and others.1–4,7,8 The list is long.

The challenge is that CES is more complex than that patient with worsening back pain and urinary changes. When we miss CES, it is often because we failed to consider the condition as a possibility. That cognitive error can lead to completing an inadequate history and exam and failing to perform the right diagnostic tests.2,9–12

It takes, on average, 11 days from onset of symptoms until the correct diagnosis is made. Many cases are missed on the first ED evaluation.13 Back pain is the most common presenting symptom, followed by saddle sensory changes and bladder dysfunction.14–17 Back pain is chronic in almost 70 percent of patients with acute CES, though up to 89 percent of patients experience a sudden worsening of symptoms within 24 hours.1–4,9,18

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Single Page

3 Responses to “Learn to Spot and Treat Cauda Equina Syndrome”

March 1, 2020

Jerry W. Jones, MD FACEP FAAEMExcellent review! Thank you!

March 1, 2020

Steven ShroyerNice analysis of diagnosing CES Brit and Alex. I was surprised at how poor each of the likelihood ratios are for this. Urinary retention appears to be nearly worthless. I see a fair number of patients with what I am calling “partial CES” and I frame it that way when speaking to the neurosurgeon because once it’s complete I assume it is permanent. This is usually in the pt who has back pain, bilateral paresthesias (or pain), has fallen but is not paralyzed and has had difficulty emptying their bladder. When combined this way maybe it has a higher +LR? In every case when I describe it as a “partial CES” to the surgeon they have performed decompressive laminectomy. Nice table of statistical characteristics. Thanks for the valuable information.

Steve Shroyer

March 1, 2020

CA Kennedy MFExcellent summary. Thanks!