Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 39 – No 02 – February 2020(click for larger image) Table 1: Features Suggesting CES

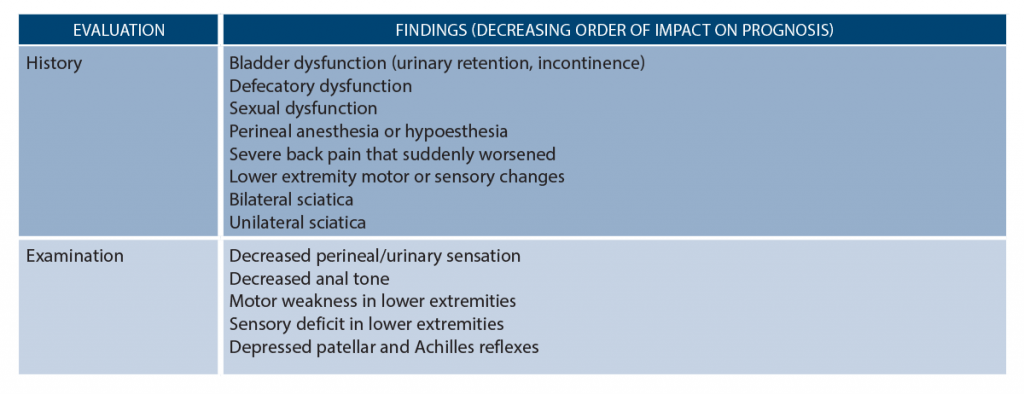

Table 1 lists red flag features for CES. Looking for urinary incontinence alone will miss CES.9–12 Along with your standard questions concerning pain severity and location, urinary changes and retention, focal neurological deficits, and perineal sensory changes, you should also ask about sexual dysfunction (erectile dysfunction), changes in sensation during urination or passing urine, and bowel function.1–4,9,18–20 When inquiring about perineal sensory changes, ask about differences in sensation with sitting, when defecating, and during hygiene activities such as wiping with toilet paper. These symptoms are frequently not offered by the patient unless directly questioned.

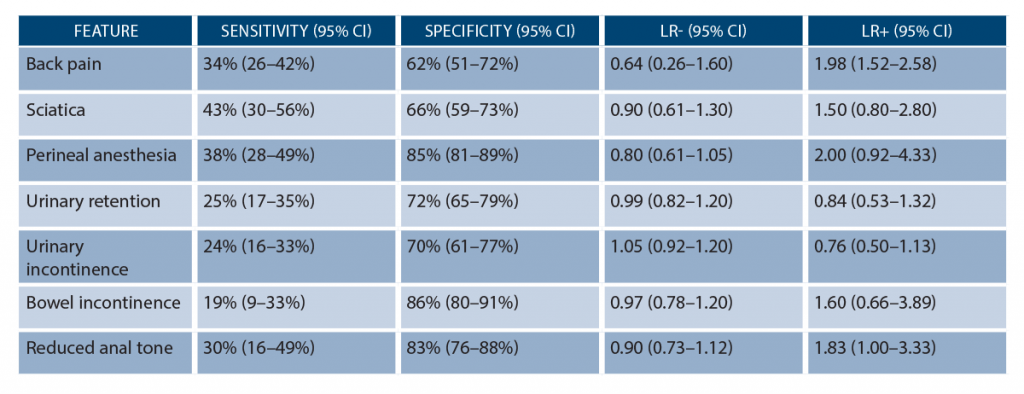

When looking at the data behind history and exam, it’s humbling how poorly these findings perform in our evaluation of CES (though we teach them with confidence). While the findings from Table 1 can suggest CES, no single finding or combination of findings can reliably diagnose or exclude CES (see Table 2). None have sensitivities over 50 percent, but perineal anesthesia and bowel incontinence possess a specificity of 85 percent and 86 percent, respectively.14–17 Urinary retention and incontinence have a specificity of 72 percent and 70 percent, respectively. What about the rectal exam? Unfortunately, rectal tone does not correlate with the severity of CES (based on studies with confirmed CES on imaging), and its reliability varies significantly among providers.21–23 While a consulting surgeon may ask you about rectal tone, don’t rely on it to rule in or rule out CES. An absent anal wink reflex, assessed by gently stroking the skin around the anus with a cotton swab or applicator and looking for contraction of the external anal sphincter, suggests sacral nerve root dysfunction.3,4,8

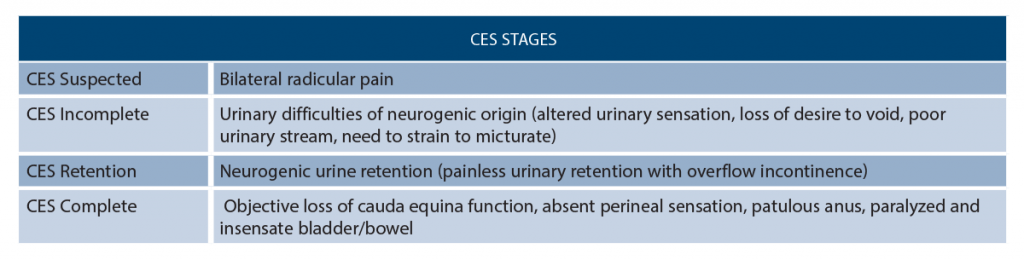

Another confusing aspect about CES is its classifications—more than 15 total!1,7,24 Rather than using all of these systems, we advocate for thinking about CES as occurring in stages (see Table 3).21 The prognosis worsens with more advanced stages (stage 4, or complete, is far worse than stage 1, or suspected).1–4,8,21,25,26 Complete CES, or stage 4, is usually associated with irreversible deficits.

Tests and Treatment

If you suspect the disease based on your history and exam, what next? Labs are not helpful. X-rays are unreliable.1,2,8,9 Bladder ultrasound for postvoid residual (PVR) can evaluate for urinary retention. In CES, urinary changes typically begin with decreased sensation of urinary flow, increased difficulty in passing urine, and sensation of incomplete emptying, followed by retention and finally overflow incontinence. There are a variety of cutoffs for PVR used to exclude CES evaluated in the literature. A PVR less than 50–100 mL strongly suggests against CES. However, values over this in combination with other signs or symptoms concerning for CES warrant further evaluation. One study suggests a PVR over 500 mL has an odds ratio of 4 for diagnosis of CES.16 The odds ratio reaches 48 for diagnosis when this is combined with two of the following: bilateral sciatica, patient subjectively experiencing urinary dysfunction, and rectal incontinence.16

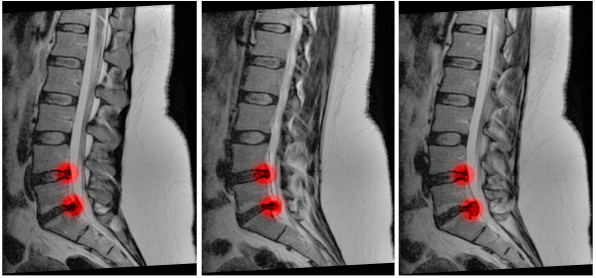

The gold standard test for suspected CES is MRI.6,17,27 However, there are several caveats. Unfortunately, there are not great data directly evaluating the ability of MRI to rule in or out the disease. A recent systematic review found MRI had a sensitivity and specificity of 81 percent for diagnosing disc herniation, though this likely underestimates the sensitivity and specificity for MRI when evaluating for CES.27 Unfortunately, MRI may not be feasible in all centers. The next best option is a CT myelogram, but this is also difficult as it requires placement of a spinal needle into the spinal canal for injection of contrast dye.28 What about lumbar and sacral CT with IV contrast? One study of 151 patients suggests that CT findings showing more than 50 percent thecal sac effacement has a specificity of 86 percent for diagnosis of CES, while less than 50 percent effacement is able to rule out CES with a sensitivity of 98 percent.29 These data have not been validated (ie, they are not ready for prime time just yet), but keep a lookout for more literature evaluating CT with contrast in the future.

If you suspect the condition based on your history, exam, and PVR, you should discuss the case with a spinal surgeon. They will assist in determining further workup and management. Treatment includes operative management in patients with CES.4,9,30–34 Data suggest patients with rapid onset of symptoms (typically defined as 24 hours) and worsening bladder function benefit the most from surgery, preferably within 24 hours of presentation.4,9,30–34 Operative delays beyond 48 hours can result in permanent dysfunction.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Single Page

3 Responses to “Learn to Spot and Treat Cauda Equina Syndrome”

March 1, 2020

Jerry W. Jones, MD FACEP FAAEMExcellent review! Thank you!

March 1, 2020

Steven ShroyerNice analysis of diagnosing CES Brit and Alex. I was surprised at how poor each of the likelihood ratios are for this. Urinary retention appears to be nearly worthless. I see a fair number of patients with what I am calling “partial CES” and I frame it that way when speaking to the neurosurgeon because once it’s complete I assume it is permanent. This is usually in the pt who has back pain, bilateral paresthesias (or pain), has fallen but is not paralyzed and has had difficulty emptying their bladder. When combined this way maybe it has a higher +LR? In every case when I describe it as a “partial CES” to the surgeon they have performed decompressive laminectomy. Nice table of statistical characteristics. Thanks for the valuable information.

Steve Shroyer

March 1, 2020

CA Kennedy MFExcellent summary. Thanks!