The Case

A 58-year-old male presents with worsening lower back pain. He has a history of L4/L5 disc disease and has been seen in this emergency department for this pain previously. Today, he says his back pain is different: It’s more severe and radiates down to both feet, and he notes some difficulty urinating. Could this be cauda equina syndrome (CES)? What should you look for on history and exam? Is there anything you can use to rule out the disease before heading to the MRI machine?

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 39 – No 02 – February 2020Characteristics of CES

We regularly see patients with severe back pain, and we are experts at screening for potentially dangerous conditions. When it comes to back pain, we are on the lookout for pyelonephritis, fracture, spinal epidural abscess/discitis, spinal epidural hematoma, mass, abdominal aortic aneurysm, retroperitoneal hematoma, and CES, as well as a variety of potential abdominal conditions.

If you think that asking back pain patients about urinary incontinence is enough, you’re going to run into trouble eventually.

The cauda equina (Latin for “horse’s tail”) is made up of the ascending and descending nerve roots from L2 to the coccygeal segments. It is responsible for lower limb movement and sensation, bladder control/urination, external anal sphincter control and defecation, sexual function, and sensation of the genitalia and perineal region.1–6 As you may have noticed, these play a huge role in our activities of daily living.

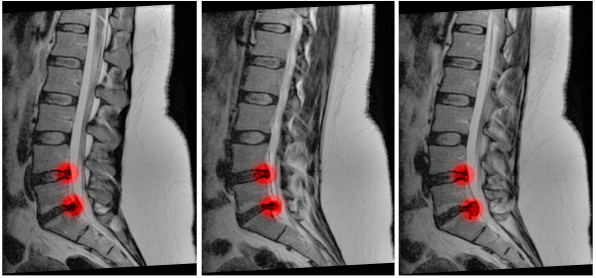

Any impingement or damage to these nerve roots may result in CES. While CES is most commonly due to central disc herniation or prolapse (usually in the setting of prior spinal disease), many conditions are associated with CES including chemotherapy, infection, radiation, vascular lesions, ischemia, trauma, epidural analgesia, and others.1–4,7,8 The list is long.

The challenge is that CES is more complex than that patient with worsening back pain and urinary changes. When we miss CES, it is often because we failed to consider the condition as a possibility. That cognitive error can lead to completing an inadequate history and exam and failing to perform the right diagnostic tests.2,9–12

It takes, on average, 11 days from onset of symptoms until the correct diagnosis is made. Many cases are missed on the first ED evaluation.13 Back pain is the most common presenting symptom, followed by saddle sensory changes and bladder dysfunction.14–17 Back pain is chronic in almost 70 percent of patients with acute CES, though up to 89 percent of patients experience a sudden worsening of symptoms within 24 hours.1–4,9,18

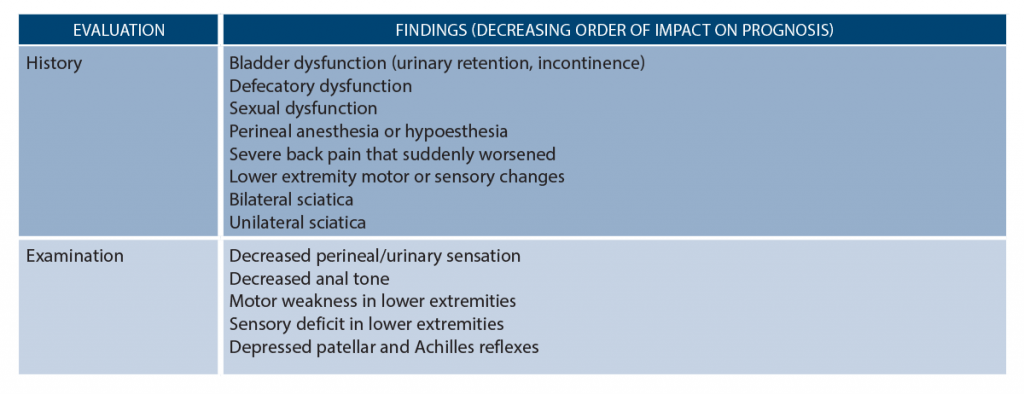

Table 1 lists red flag features for CES. Looking for urinary incontinence alone will miss CES.9–12 Along with your standard questions concerning pain severity and location, urinary changes and retention, focal neurological deficits, and perineal sensory changes, you should also ask about sexual dysfunction (erectile dysfunction), changes in sensation during urination or passing urine, and bowel function.1–4,9,18–20 When inquiring about perineal sensory changes, ask about differences in sensation with sitting, when defecating, and during hygiene activities such as wiping with toilet paper. These symptoms are frequently not offered by the patient unless directly questioned.

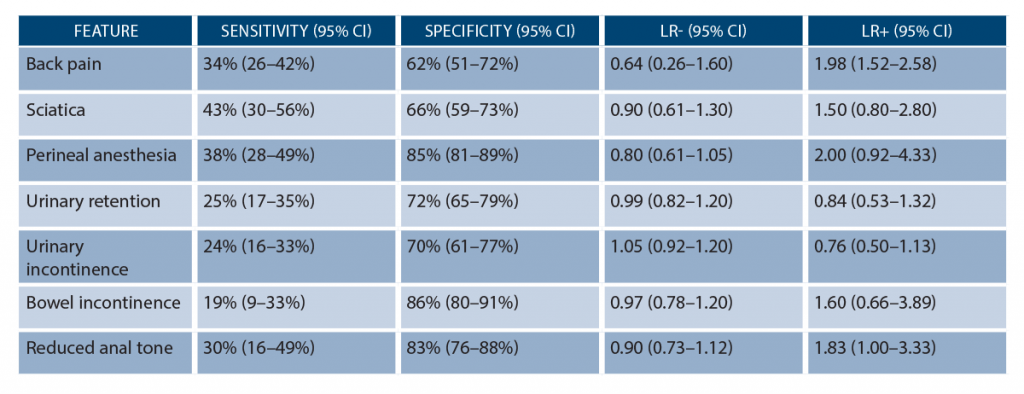

When looking at the data behind history and exam, it’s humbling how poorly these findings perform in our evaluation of CES (though we teach them with confidence). While the findings from Table 1 can suggest CES, no single finding or combination of findings can reliably diagnose or exclude CES (see Table 2). None have sensitivities over 50 percent, but perineal anesthesia and bowel incontinence possess a specificity of 85 percent and 86 percent, respectively.14–17 Urinary retention and incontinence have a specificity of 72 percent and 70 percent, respectively. What about the rectal exam? Unfortunately, rectal tone does not correlate with the severity of CES (based on studies with confirmed CES on imaging), and its reliability varies significantly among providers.21–23 While a consulting surgeon may ask you about rectal tone, don’t rely on it to rule in or rule out CES. An absent anal wink reflex, assessed by gently stroking the skin around the anus with a cotton swab or applicator and looking for contraction of the external anal sphincter, suggests sacral nerve root dysfunction.3,4,8

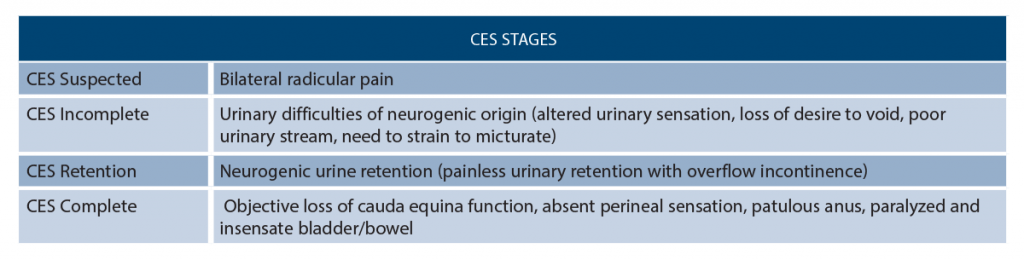

Another confusing aspect about CES is its classifications—more than 15 total!1,7,24 Rather than using all of these systems, we advocate for thinking about CES as occurring in stages (see Table 3).21 The prognosis worsens with more advanced stages (stage 4, or complete, is far worse than stage 1, or suspected).1–4,8,21,25,26 Complete CES, or stage 4, is usually associated with irreversible deficits.

Tests and Treatment

If you suspect the disease based on your history and exam, what next? Labs are not helpful. X-rays are unreliable.1,2,8,9 Bladder ultrasound for postvoid residual (PVR) can evaluate for urinary retention. In CES, urinary changes typically begin with decreased sensation of urinary flow, increased difficulty in passing urine, and sensation of incomplete emptying, followed by retention and finally overflow incontinence. There are a variety of cutoffs for PVR used to exclude CES evaluated in the literature. A PVR less than 50–100 mL strongly suggests against CES. However, values over this in combination with other signs or symptoms concerning for CES warrant further evaluation. One study suggests a PVR over 500 mL has an odds ratio of 4 for diagnosis of CES.16 The odds ratio reaches 48 for diagnosis when this is combined with two of the following: bilateral sciatica, patient subjectively experiencing urinary dysfunction, and rectal incontinence.16

The gold standard test for suspected CES is MRI.6,17,27 However, there are several caveats. Unfortunately, there are not great data directly evaluating the ability of MRI to rule in or out the disease. A recent systematic review found MRI had a sensitivity and specificity of 81 percent for diagnosing disc herniation, though this likely underestimates the sensitivity and specificity for MRI when evaluating for CES.27 Unfortunately, MRI may not be feasible in all centers. The next best option is a CT myelogram, but this is also difficult as it requires placement of a spinal needle into the spinal canal for injection of contrast dye.28 What about lumbar and sacral CT with IV contrast? One study of 151 patients suggests that CT findings showing more than 50 percent thecal sac effacement has a specificity of 86 percent for diagnosis of CES, while less than 50 percent effacement is able to rule out CES with a sensitivity of 98 percent.29 These data have not been validated (ie, they are not ready for prime time just yet), but keep a lookout for more literature evaluating CT with contrast in the future.

If you suspect the condition based on your history, exam, and PVR, you should discuss the case with a spinal surgeon. They will assist in determining further workup and management. Treatment includes operative management in patients with CES.4,9,30–34 Data suggest patients with rapid onset of symptoms (typically defined as 24 hours) and worsening bladder function benefit the most from surgery, preferably within 24 hours of presentation.4,9,30–34 Operative delays beyond 48 hours can result in permanent dysfunction.

Case Resolution

Your exam demonstrates decreased perineal sensation and weakness in L5 bilaterally. When questioned, the patient also highlights changes in bowel function. The patient’s PVR is 400 mL, and you call the surgeon, who asks for an MRI. The MRI demonstrates central disc protrusion at L5/S1. The patient is admitted and taken to the operating room.

Dr. Long is an emergency physician in the San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium at Fort Sam Houston, Texas.

Dr. Koyfman (@EMHighAK) is assistant professor of emergency medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center and an attending physician at Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas.

References

- Tarulli AW. Disorders of the cauda equina. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2015;21(1 Spinal Cord Disorders):146-158.

- Gardner A, Gardner E, Morley T. Cauda equina syndrome: a review of the current clinical and medico-legal position. Eur Spine J. 2011;20(5):690-697.

- Mauffrey C, Randhawa K, Lewis C, et al. Cauda equina syndrome: an anatomically driven review. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2008;69(6):344-347.

- Greenhalgh S, Finucane L, Mercer C, et al. Assessment and management of cauda equina syndrome. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2018;37:69-74.

- Moore KL. Clinically oriented anatomy. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1992.

- McNamee J, Flynn P, O’Leary S, et al. Imaging in cauda equina syndrome—a pictorial review. Ulster Med J. 2013;82(2):100-108.

- Fraser S, Roberts L, Murphy E. Cauda equina syndrome: a literature review of its definition and clinical presentation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(11):1964-1968.

- Kapetanakis S, Chaniotakis C, Kazakos C, et al. Cauda equina syndrome due to lumbar disc herniation: a review of literature. Folia Med (Plovdiv). 2017;59(4):377-386.

- Kavanagh M, Walker J. Assessing and managing patients with cauda equina syndrome. Br J Nurs. 2013;22(3):134-137.

- Small SA, Perron AD, Brady WJ. Orthopedic pitfalls: cauda equina syndrome. Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23(2):159-163.

- Kostuik JP. Medicolegal consequences of cauda equina syndrome: an overview. Neurosurg Focus. 2004;16(6):e8.

- Markham DE. Cauda equina syndrome: diagnosis, delay and litigation risk. Curr Orthop. 2004;18(1):58-62.

- Fuso FA, Dias AL, Letaif OB, et al. Epidemiological study of cauda equina syndrome. Acta Ortop Bras. 2013;21(3):159-162.

- Korse NS, Pijpers JA, van Zwet E, et al. Cauda equina syndrome: presentation, outcome, and predictors with focus on micturition, defecation, and sexual dysfunction. Eur Spine J. 2017;26(3):894-904.

- Fairbank J, Hashimoto R, Dailey A, et al. Does patient history and physical examination predict MRI proven cauda equina syndrome? Evid Based SpineCare J. 2011;2(4):27-33.

- Domen PM, Hofman PA, van Santbrink H, et al. Predictive value of clinical characteristics in patients with suspected cauda equina syndrome. Eur J Neurol. 2009;16(3):416-419.

- Dionne N, Adefolarin A, Kunzelman D, et al. What is the diagnostic accuracy of red flags related to cauda equina syndrome (CES), when compared to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)? A systematic review. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2019;42:125-133.

- Gleave JR, Macfarlane R. Cauda equina syndrome: what is the relationship between timing of surgery and outcome? Br J Neurosurg. 2002;16(4):325-328.

- Greenhalgh S, Truman C, Webster V, et al. Development of a toolkit for early identification of cauda equina syndrome. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2016;17:559-567.

- Pronin S, Hoeritzauer I, Statham PF, et al. Are we neglecting sexual function assessment in suspected cauda equina syndrome? Surgeon. 2019. pii: S1479-666X(19)30037-X.

- Todd NV, Dickson RA. Standards of care in cauda equina syndrome. Br J Neurosurg. 2016;30(5):518-522.

- Gooding BW, Higgins MA, Calthorpe DA. Does rectal examination have any value in the diagnosis of cauda equina syndrome? Br J Neurosurg. 2013;27(2):156-159.

- Sherlock KE, Turner W, Elsayed S, et al. The evaluation of digital rectal examination for assessment of anal tone in suspected cauda equina syndrome. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2015;40(15):1213-1218.

- Todd NV. Guidelines for cauda equina syndrome. Red flags and white flags. Systematic review and implications for triage. Br J Neurosurg. 2017;31(3):336-339.

- Mukherjee S, Thakur B, Crocker M. Cauda equina syndrome: a clinical review for the frontline clinician. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2013;74(8):460-464.

- Goodman BP. Disorders of the cauda equina. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2018;24(2, Spinal Cord Disorders):584-602.

- Kim JH, van Rijn RM, van Tulder MW, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of diagnostic imaging for lumbar disc herniation in adults with low back pain or sciatica is unknown; a systematic review. Chiropr Man Therap. 2018;26:37.

- Ozdoba C, Gralla J, Rieke A, et al. Myelography in the age of MRI: why we do it, and how we do it. Radiol Res Pract. 2011;2011:329017.

- Peacock JG, Timpone VM. Doing more with less: diagnostic accuracy of CT in suspected cauda equina syndrome. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2017;38(2):391-397.

- Chau AM, Xu LL, Pelzer NR, et al. Timing of surgical intervention in cauda equina syndrome: a systematic critical review. World Neurosurg. 2014;81(3-4):640-650.

- Shapiro S. Medical realities of cauda equina syndrome secondary to lumbar disc herniation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(3):348-351; discussion 352.

- Ahn UM, Ahn NU, Buchowski JM, et al. Cauda equina syndrome secondary to lumbar disc herniation: a meta-analysis of surgical outcomes. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(12):1515-1522.

- Aly TA, Aboramadan MO. Efficacy of delayed decompression of lumbar disk herniation causing cauda equina syndrome. Orthopedics. 2014;37(2):e153-156.

- Thakur JD, Storey C, Kalakoti P, et al. Early intervention in cauda equina syndrome associated with better outcomes: a myth or reality? Insights from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database (2005–2011). Spine J. 2017;17(10):1435-1448.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

3 Responses to “Learn to Spot and Treat Cauda Equina Syndrome”

March 1, 2020

Jerry W. Jones, MD FACEP FAAEMExcellent review! Thank you!

March 1, 2020

Steven ShroyerNice analysis of diagnosing CES Brit and Alex. I was surprised at how poor each of the likelihood ratios are for this. Urinary retention appears to be nearly worthless. I see a fair number of patients with what I am calling “partial CES” and I frame it that way when speaking to the neurosurgeon because once it’s complete I assume it is permanent. This is usually in the pt who has back pain, bilateral paresthesias (or pain), has fallen but is not paralyzed and has had difficulty emptying their bladder. When combined this way maybe it has a higher +LR? In every case when I describe it as a “partial CES” to the surgeon they have performed decompressive laminectomy. Nice table of statistical characteristics. Thanks for the valuable information.

Steve Shroyer

March 1, 2020

CA Kennedy MFExcellent summary. Thanks!