The Case

A 33-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath. She checked into the emergency department at 3:41 a.m. with respiratory symptoms. She had a complex history including type 1 diabetes, end-stage renal disease on dialysis, tetralogy of Fallot, and a partial pancreatectomy. Her triage vitals showed a blood pressure of 177/97, a pulse of 86 beats per minute, a pulse oximetry of 94 percent on room air, and a temperature of 98.7° F.

She was seen by an emergency physician. The history noted that her shortness of breath started at 7 p.m., about 8.5 hours earlier. It was worsened by lying flat and improved when she was sitting upright. She had been dialyzed one day earlier. The examination revealed normal breath sounds and no cardiac abnormality. No significant abnormalities were noted on her examination. Laboratory orders included a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, troponin, pro-brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), chest X-ray, and an ECG. The results were noteworthy for a hemoglobin of 7.7 g/dL, glucose of 418 mg/dL, creatinine of 3.9 mg/dL, BNP >5,000 pg/mL, and negative troponin.

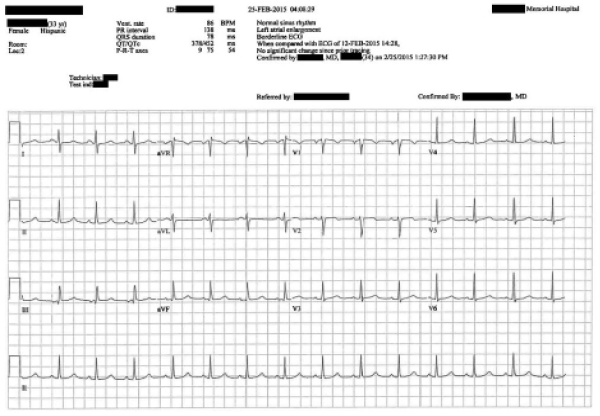

The ECG is shown in Figure 1.

Her chest X-ray was read as “Stable cardiomegaly. There is pulmonary vascular congestion and interstitial infiltrates. Findings suggest fluid overload with congestive failure.”

After reviewing these results, the physician ordered 15 units of insulin SQ (Humulin R). The patient was feeling nauseated and in pain, and so she was given ondansetron 4 mg oral disintegrating tablet and an intramuscular dose of hydromorphone 1 mg. After IV access was obtained, she was given a repeat dose of hydromorphone 1 mg.

Her blood glucose improved to 313 mg/dL. The doctor reassessed the patient, and she was doing well (see Figure 2). Given her reassuring vitals and improving blood glucose, she was discharged from the emergency department.

Figure 2: Progress note before discharge.

The discharge instructions advised her to follow up at her next scheduled dialysis appointment the next day and to return if her symptoms worsened. After she was discharged, she was taken back to the lobby of the emergency department, where she was going to wait several hours for a ride home.

Around 7:25 a.m., another patient in the waiting room suddenly came to the front desk to report that the patient had collapsed.

She was rushed back into the emergency department, where it was discovered that she was pulseless. After a few minutes of chest compressions, return of spontaneous circulation occurred. She was given calcium chloride and sodium bicarbonate due to suspicion for hyperkalemia, but her potassium was only 4.3 mmol/L on repeat blood work. She was intubated and admitted to the ICU.

Later that day, the emergency physician who intubated her went back to the chart and made an addendum (see Figure 3)

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

One Response to “Lesson Learned: Delayed Documentation Can Lead to Suspicion”

October 24, 2021

Anthony PohlgeersThere will always be suspicion in anything we document. Not documenting this finding would also be suspicious; especially if it came out in RN or RT testimony later. This addendum was timed appropriately and certainly while the patient was fresh to the ICU and when ‘final outcome’ could not have been known by this physician. My vote would be document this ‘remembrance’ even if suspicion is generated in retrospect.