Explore This Issue

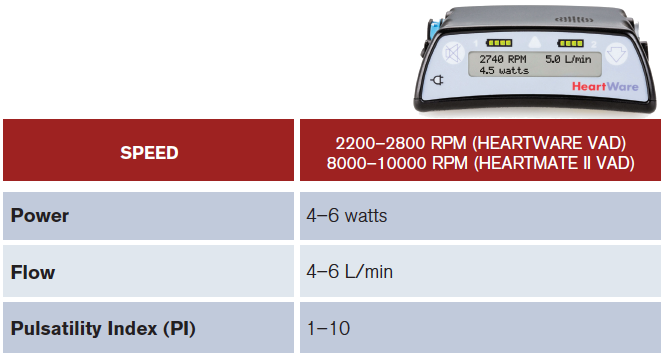

ACEP Now: Vol 36 – No 08 – August 2017(click for larger image) Table 1: Control Device: Normal Values.

PI varies from patient to patient. It changes with volume status and it also reflects how much cardiac output is provided by the pump versus the patient. The higher the PI, the less the amount of unloading done by the pump and increased native heart function. A decrease preload will also lead to a decrease in PI.2

PHOTO: Medtronic

Battery Dead or Low

If the battery power is low, the batteries need to be replaced immediately. Whatever you do, don’t disconnect both batteries at once. If the controller is disconnected from both batteries at the same time, the LVAD will lose power and stop working, so the batteries must be replaced one at a time.3

Hypotension (ie, MAP <60)

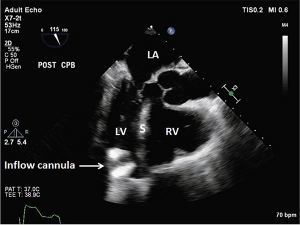

The LVAD is highly preload dependent, which makes it sensitive to alterations in volume status (eg, dehydration, bleeding, thrombosis, diarrhea, and vomiting). Volume resuscitation is a mainstay in therapy.2 Another cause of hypotension is a suction event in which the LV is not filling but the pump continues to attempt to pull blood from it (see Figure 3).4 During the event, the LVAD sucks down the walls of the LV to an abnormally small size, leading to a right to left ventricular septal shift.1 This phenomenon is a result of any condition that produces LV underfilling, including hypovolemia, right ventricle (RV) failure, cardiac tamponade, or pulmonary hypertension, all of which can be observed on bedside cardiac ultrasound. These events can also be associated with ventricular dysrhythmias resulting in syncope and death.

Figure 3: Suction Event, LV < RV.

The inflow cannula turned and faced the interventricular septum. LA = left atrium; LV = left ventricle; S = interventricular septum; RV = right ventricle.

Source: J Thorac Dis. 2015;7(12):2139-2150.

Bleeding

LVAD patients are typically anticoagulated and are predisposed to the development of arteriovenous malformations along the gastrointestinal (GI) mucosa, making GI bleeds the second most common complication.2 Patients can also develop acquired von Willebrand syndrome from the breakdown of von Willebrand multimers from the shearing forces created by the LVAD itself.2 Holding anticoagulation is appropriate in the setting of acute GI hemorrhage. Consider using tranexamic acid, prothrombin complex concentrate, or fresh frozen plasma in LVAD patients with unstable bleeding, in coordination with the LVAD team.

Pump Thrombosis

Pump thrombosis occurs in 1 to 2 percent of all patients at two years’ post implantation.1 Suspect the diagnosis if there is significant increase in pump power (>10–13 watts) with decreased flow and the patient is complaining of fatigue and dark urine.2 Quickly obtain a bedside cardiac ultrasound. On ultrasound, the LV will seem to be unloading improperly with no other explanation and both the LV and RV will be dilated. Hemolysis is also suggested by worsening renal function, scleral icterus, and elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase >2.5 times the upper limit.2 Treat them with anticoagulation using unfractionated heparin, and in life threatening cases (eg, coding) consider using thrombolytic therapy (eg, tissue plasminogen activator).

Increased Afterload

Increased afterload can occur from outflow obstruction or systemic hypertension. Elevated MAP >90 mmHg may reduce cardiac output and perfusion resulting in cerebral vascular ischemia or hemorrhage. Promptly manage blood pressure with afterload-reducing medications to maintain a goal MAP of 70 mmHg.2 ACE inhibitors and beta blockers are the preferred agents, but hydralazine and nitrates may also be used on an individual basis.5

Infection

Infection is the most common complication of long-term LVAD use.2 Multiple sites can be affected, but driveline infections (DLI) remain the most common. Approximately 80 percent of DLIs occur between 30 days and six months after implantation. Clinical presentations vary from mild pain to fever, warmth, and purulent discharge at the driveline exit site. In a 2013 retrospective review of 247 LVAD patients, only half of patients presented with fever, leukocytosis, or systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria.6 DLIs can also extend into the pump pocket and lead to bloodstream infection and endocarditis. Treat with early IV fluids and broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy (ie, cefazolin, vancomycin, and linezolid) covering for Staphylococcus aureus, coagulase-negative Staph and gram-negative bacilli (Klebsiella, Pseudomonas).2 These patients will also need to be transferred to the nearest LVAD facility for more definite treatment (ie, LVAD replacement).2

Dysrhythmias

Postsurgical scarring can alter the conduction system within the myocardium, predisposing to ventricular dysrhythmias. The incidence of sustained ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation is 56 percent with the highest prevalence in the first postoperative month.2,7 Fortunately, the treatment is no different than in patients without LVADs, and cardioversion is indicated if the patient becomes hemodynamically unstable.2 Management of a stable patient includes an IV fluid bolus and emergent echocardiogram. Intravenous amiodarone is the first line agent for dysrhythmias, but lidocaine and procainamide can also be used.5 It is recommended that the LVAD system controller be disconnected from the device briefly during the time of cardioversion.

Cardiac Arrest

If an LVAD patient suddenly becomes unresponsive with signs of poor perfusion it may be appropriate to initiate CPR until the LVAD team can be consulted for further management.2 LVAD patients in cardiac arrest may also be defibrillated if needed, and this is best performed with an anterior-posterior placement of the pads. LVAD manufacturers currently do not recommend chest compressions for fear of dislodging the device. Despite the dearth of data to support this, a recent retrospective case series by Shinar and colleagues of eight patients with LVADs who received CPR during cardiac arrest demonstrated no dislodgement of LVAD devices.8

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

5 Responses to “How to Manage Emergency Department Patients with Left Ventricular Assist Devices”

August 23, 2017

Z BasThis is a great review. Thank you so much. I feel like I now have an approach to LVAD patients, should they ever come into my ED.

August 27, 2017

RobErrata: Under Bleeding, should read “arteriovenous malformations” in the GI tract.

Great article!

August 28, 2017

Dawn Antoline-WangThank you, we’ve made the correction.

August 31, 2017

CRThanks for a great concise review!

October 14, 2017

Kevin WebbThank you for the great review. I will forward this to our Paramedics.