Pain

Opioids are also the principal treatment for pain in terminally ill patients. Intravenous administration of opioids is generally best for controlling severe nociceptive pain that is new or escalating, whereas oral medication can be better for chronic mild or moderate pain if the patient tolerates oral administration.2–4 Given the rapid peak plasma concentration (six minutes) and short half-life of IV opioids, patients should be reassessed every 15 minutes for repeated doses. The half-life of morphine and hydromorphone is approximately two hours. The duration of action of fentanyl is only 30 minutes to an hour.6

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 40 – No 07 – July 2021When assessing a patient who presents to the emergency department with an acute pain exacerbation despite the use of their home medications, emergency physicians should calculate the 24-hour dose of their prescribed opioids and use an equianalgesic dosage conversion calculator so the patient is appropriately medicated. When converting from an oral morphine equivalent to another opioid in a patient with a high opioid requirement, emergency physicians should reduce the total dosage of the new opioid medication by 25 to 50 percent. Be cautious in terminally ill patients who may have renal impairment and avoid morphine, as this can lead to opioid-induced neurotoxicity. Use hydromorphone or fentanyl as the opioid of choice if there is known renal impairment.

Infusions Versus Push Dose IV

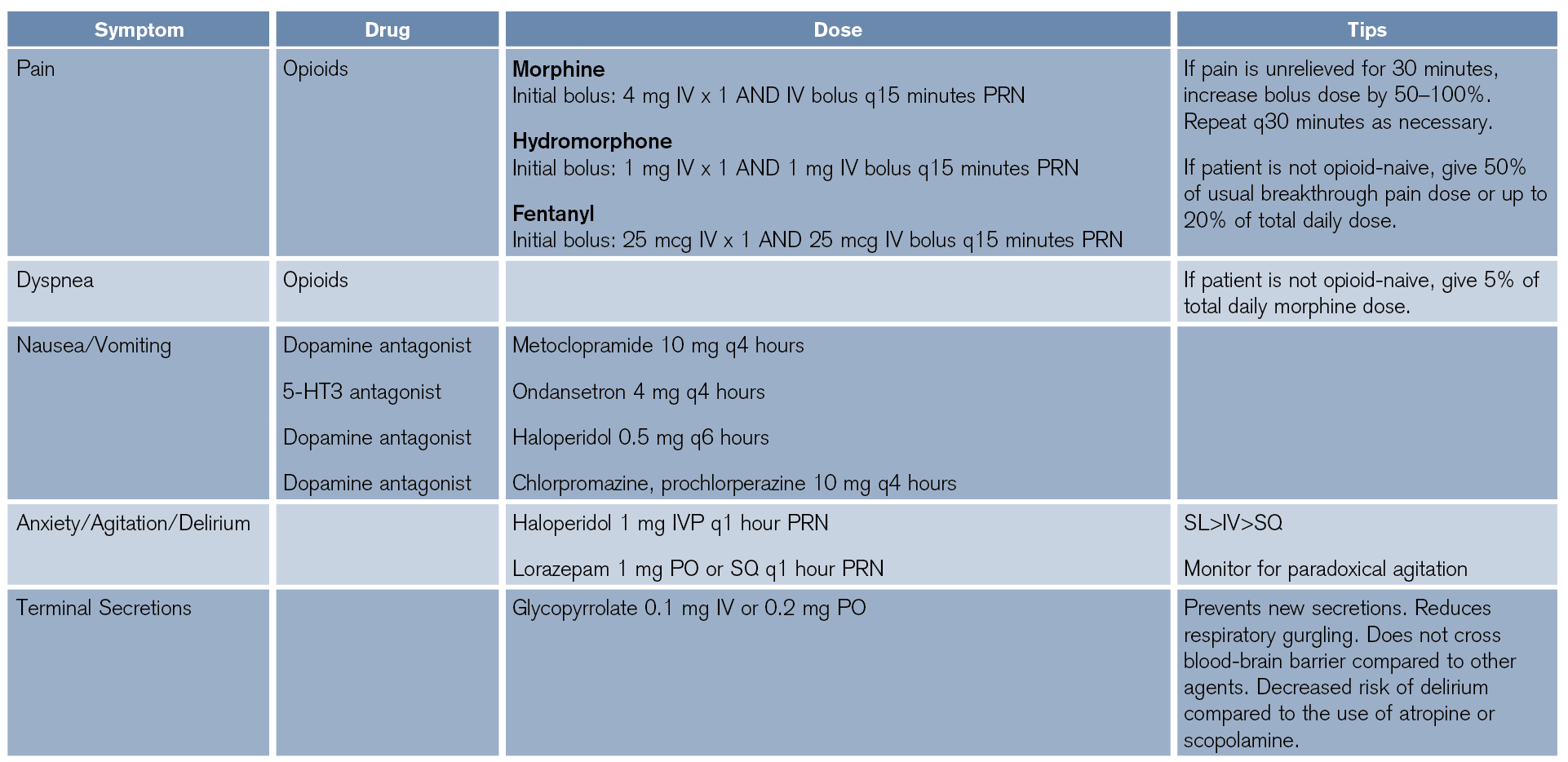

The dose of opioids for pain management in the dying patient should be increased by 50 to 100 percent regardless of the starting dose until pain is adequately controlled. Infusions are less effective in the short-term emergency setting, as they require four to five half-lives to reach steady plasma concentration, which can take up to 10 hours.6 Bolus doses outlined in Table 1 are recommended, and infusions can be considered as a supplement if long-term pain management is necessary.

(click for larger image) Table 1: Palliative Medical Management of Symptoms in the Acutely Dying Patient

The Principle of Double Effect

The “principle of double effect” is an ethical doctrine that indicates that an action with both intended and unintended outcomes is justified if the intended benefit significantly outweighs the unintended harm.7 This has historically been applicable to the concern that opioids may depress respiratory drive and therefore accelerate the dying process. While the use of opioids is widely considered justified by the principle of double effect, there is evidence that opioids do not actually hasten death when used appropriately for pain in the actively dying patient, particularly at low doses.8–10 One study found that opioid use titrated to comfort in a palliative setting does not significantly alter PaCO2, PaO2, or overall survival. It does, however, manage pain and reduce dyspnea, thereby significantly increasing comfort at the end of life.1,9,10

One notable exception of the double effect is in conscious patients with imminent airway loss. These patients require rapid and large boluses of opioids or benzodiazepines, propofol, ketamine, barbiturate, etc. The ultimate result would be palliative sedation, which is necessary in this instance to mitigate suffering from significant dyspnea.8

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Single Page

No Responses to “Managing Pain Relief in Palliative Care”