Similarly, when I first used hypnosis for patients with emergencies in the emergency department or in wilderness settings, most of my colleagues considered it to be improvisation, or at least at the limits of acceptable nonpsychiatric medical practice, until professional journal publications highlighted its usefulness.1,2 One lifesaving technique I originally designed as an improvisation involved inserting a handheld injection needle as an intraosseous line above the medial malleolus; it is now an accepted part of advanced life support curricula.3,4

I have found that successful improvisations happen after one has read, thought about, and, often, discussed and practiced how to handle specific situations. For example, the rapid evacuation of multiple hospital patients during a disaster is usually accomplished using improvised equipment. Most hospital disaster plans, however, suggest that the local fire department will evacuate multiple patients down long stairways, an idea that is impracticable in a real-life emergency and frankly ludicrous. Rather, hospitals need to train their staff in proven improvised methods, such as using a bedsheet to drag patients to and then down stairways lined with bed mattresses.5

Lifesaving medical improvisation is not common. When it occurs in public view, it receives international notice. That was the case in 1995 when a surgeon used a knife, fork, and coat hanger sterilized in cognac to insert a urinary catheter with a coat hanger stent for a pneumothorax aboard a British Airlines flight from Hong Kong to London.6 Similarly, dramatic improvisations have appeared sporadically in medical journals over the last few decades.7,8

Gap Between Reality TV and Real Life

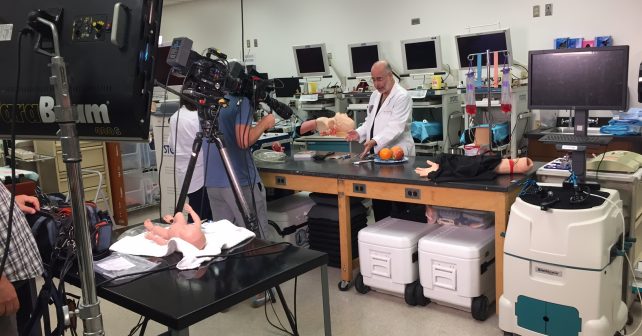

Real medical improvisation involves the materials that are available and personnel who have studied and discussed the presenting problem to attempt to provide benefit, not always successfully, for the patient. Improvisation as portrayed in the media relies on having the appropriate materials readily on hand and a physician just eccentric enough to use them whenever a patient is in a desperate situation—every week in some cases.

Overblown fantasy has always been a part of the TV landscape, and medical storytelling is no exception. As health care professionals, we don’t need to rely on “fake news,” an out-of-the-box genius, or extraordinary measures. We can use our expertise augmented with research, discussion, and creativity to respond to every emergency situation in the best way possible.

References

- Iserson KV. Reducing dislocations in a wilderness setting: use of hypnosis and intraarticular anesthesia. J Wilderness Med. 1991;2:22-26.

- Iserson KV. An hypnotic suggestion: review of hypnosis for clinical emergency care. J Emerg Med. 2014;46(4):588-596.

- Iserson KV, Criss E. Intraosseous infusions—a usable technique. Am J Emerg Med. 1986;4(6):540-542.

- Iserson KV. Intraosseous infusions in adults. J Emerg Med. 1989;7(6):587-592.

- Iserson KV. Vertical hospital evacuations: a new method. South Med J. 2013;106(1):37-42.

- Surgery at 33,000 feet. Newsweek. June 4, 1995.

- Iserson KV, Luke-Blyden Z, Clemans S. Orbital compartment syndrome: alternative tools to perform a lateral canthotomy and cantholysis. Wilderness Environ Med. 2016;27(1):85-91.

- Lin G, Lavon H, Gelfond R, et al. Hard times call for creative solutions: medical improvisations at the Israel Defense Forces Field Hospital in Haiti. Am J Disaster Med. 2010;5(3):188-192.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

No Responses to “Medical Improvisation and the Media”