Medical improvisation is a subject with which I have had a lot of experience throughout my career. Not only have I written articles about improvised techniques and used them both in my emergency medicine practice and as a long-time member of a wilderness search and rescue team, I also continue to use them in my “retirement,” during which I am actively engaged in disaster and international medicine.

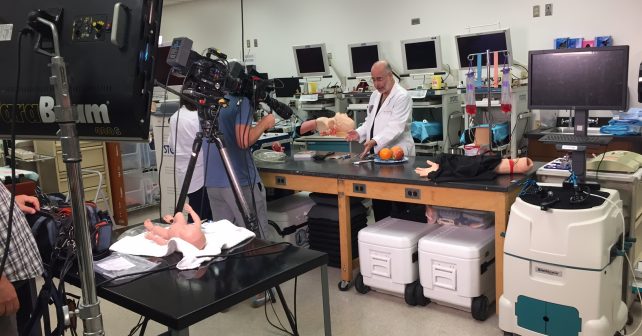

As part of a recent interview, I was asked to demonstrate or discuss several improvised techniques that I have used. These included making an endotracheal tube from an available (often a suction) tube and a baby bottle nipple (less than a minute); fashioning a scalpel using a razor, Super Glue, and a spoon (about five minutes to let the glue set); using hypnosis for multiple procedures, most often joint relocations or fracture reductions (usually about three minutes); making a nasal speculum from a coat hanger (one to two minutes); and doing intraosseous infusions above the medial malleolus (less than a minute). I also gave them pictures and videos of my doing pediatric intraperitoneal infusions (for dehydration) and digital and blind nasotracheal intubations, as well as making a Foley catheter–condom device to stop postpartum bleeding and a “swagged” suture (suture attached to the needle).

Does Medical Improvisation on TV Send the Wrong Message?

However, upon reflection, I’ve grown concerned about how watching medical improvisation on television shows shapes the public’s perception of real-life medical practice.

Sometimes, TV doctors use unusual methods drawn from medical literature, which TV writers or medical consultants discover while planning an episode. I’m guilty of contributing to that literature with a number of articles and my book Improvised Medicine: Providing Care in Extreme Environments. However, imaginative writers on nearly every medical show occasionally “jump the shark;” they’ve run out of plausible ideas and have resorted to using an extreme and unlikely plot.

I don’t mean to say that using improvisation is implausible, just that it’s never as easy, rarely as successful as traditional approaches, and absolutely not as frequent as these shows suggest. When TV or movie doctors reach for a pen to do a cricothyrotomy or for the too-handy tube and jug for thoracostomy, they inevitably and dramatically save a life. Unfortunately, reality differs from TV melodramas; there is not always a joyous outcome.

I have directed my publications at health care professionals, such as physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and paramedics, who sporadically must deal with resource scarcity. They may be practicing in less-developed countries or wilderness areas, aboard isolated vehicles (eg, ships or planes), disaster settings, or even their own emergency department when a local catastrophe or bad management leaves them without the tools, supplies, power, or water they would ordinarily use to help their patients.

Real-Life Improv Successes

Of course, no knowledgeable health care professional uses novel improvisations every day, even when in the most resource-poor areas. When they find something that works, they and their colleagues adopt it, and the improvisation transforms into good clinical practice. Such was the case when, as a medical neophyte, I watched my resident and the attending construct a ventilator for infants out of a Rube Goldberg–like assortment of parts when no such ventilator had yet been made. (Rube Goldberg was a cartoonist known for drawing amazingly complicated devices.) Eventually, devices such as the one they devised morphed into the Baby Bird ventilator, and today, infant ventilators are standard equipment.

Similarly, when I first used hypnosis for patients with emergencies in the emergency department or in wilderness settings, most of my colleagues considered it to be improvisation, or at least at the limits of acceptable nonpsychiatric medical practice, until professional journal publications highlighted its usefulness.1,2 One lifesaving technique I originally designed as an improvisation involved inserting a handheld injection needle as an intraosseous line above the medial malleolus; it is now an accepted part of advanced life support curricula.3,4

I have found that successful improvisations happen after one has read, thought about, and, often, discussed and practiced how to handle specific situations. For example, the rapid evacuation of multiple hospital patients during a disaster is usually accomplished using improvised equipment. Most hospital disaster plans, however, suggest that the local fire department will evacuate multiple patients down long stairways, an idea that is impracticable in a real-life emergency and frankly ludicrous. Rather, hospitals need to train their staff in proven improvised methods, such as using a bedsheet to drag patients to and then down stairways lined with bed mattresses.5

Lifesaving medical improvisation is not common. When it occurs in public view, it receives international notice. That was the case in 1995 when a surgeon used a knife, fork, and coat hanger sterilized in cognac to insert a urinary catheter with a coat hanger stent for a pneumothorax aboard a British Airlines flight from Hong Kong to London.6 Similarly, dramatic improvisations have appeared sporadically in medical journals over the last few decades.7,8

Gap Between Reality TV and Real Life

Real medical improvisation involves the materials that are available and personnel who have studied and discussed the presenting problem to attempt to provide benefit, not always successfully, for the patient. Improvisation as portrayed in the media relies on having the appropriate materials readily on hand and a physician just eccentric enough to use them whenever a patient is in a desperate situation—every week in some cases.

Overblown fantasy has always been a part of the TV landscape, and medical storytelling is no exception. As health care professionals, we don’t need to rely on “fake news,” an out-of-the-box genius, or extraordinary measures. We can use our expertise augmented with research, discussion, and creativity to respond to every emergency situation in the best way possible.

References

- Iserson KV. Reducing dislocations in a wilderness setting: use of hypnosis and intraarticular anesthesia. J Wilderness Med. 1991;2:22-26.

- Iserson KV. An hypnotic suggestion: review of hypnosis for clinical emergency care. J Emerg Med. 2014;46(4):588-596.

- Iserson KV, Criss E. Intraosseous infusions—a usable technique. Am J Emerg Med. 1986;4(6):540-542.

- Iserson KV. Intraosseous infusions in adults. J Emerg Med. 1989;7(6):587-592.

- Iserson KV. Vertical hospital evacuations: a new method. South Med J. 2013;106(1):37-42.

- Surgery at 33,000 feet. Newsweek. June 4, 1995.

- Iserson KV, Luke-Blyden Z, Clemans S. Orbital compartment syndrome: alternative tools to perform a lateral canthotomy and cantholysis. Wilderness Environ Med. 2016;27(1):85-91.

- Lin G, Lavon H, Gelfond R, et al. Hard times call for creative solutions: medical improvisations at the Israel Defense Forces Field Hospital in Haiti. Am J Disaster Med. 2010;5(3):188-192.

Dr. Iserson is professor emeritus in the department of emergency medicine at the University of Arizona in Tucson.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Medical Improvisation and the Media”