The Case

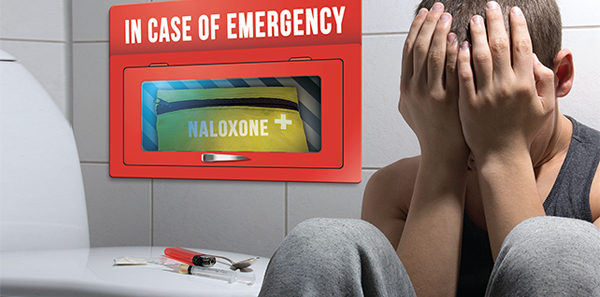

A 57-year-old man is brought in by family in a private vehicle after a “heroin overdose.” The patient had just gotten out of rehab and was doing well until that day, when the family found him blue and unresponsive. The patient regains spontaneous respirations and normal oxygenation after two doses of naloxone in the ED. He is clinically stable after several hours of observation in the ED, and you think he is ready for discharge. What do you have available in your ED to prevent a recurrent overdose or overdose death?

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 35 – No 03 – March 2016Given the high prevalence of opioid dependency and abuse among emergency department patients and the increasing frequency of overdose-related ED visits, emergency physicians have an opportunity to prevent opioid overdose deaths.1–3 ED naloxone distribution is a simple, cost-effective way to provide a lifesaving intervention.4–7 In August 2015, the ACEP Trauma & Injury Prevention Section organized a webinar on practical considerations when starting a program. Key considerations every ED naloxone program must consider include program implementation and utilization, policies and regulations, means of distribution, cost, and patient education.

Program Implementation and Utilization

Primary factors influencing program utilization include knowledge of literature-based evidence; policies and laws; ED/hospital support, policies, and procedures; professional organizations’ policies and guidelines; and cost/payment mechanisms. Program incorporation into normal work routines can diminish utilization barriers and facilitate support. Policies, procedures, and expectations should be easy to understand and readily accessible.

Patient barriers to naloxone—including stigma, mistrust of medical providers, fear of legal consequences for possession or use, and fear of withdrawal after receiving naloxone—should be addressed. Building patient trust and soliciting feedback will improve program acceptability and quality.

Prominent provider barriers include negative attitudes toward addiction, lack of knowledge about naloxone, and lack of clarity about who should receive naloxone. We recommend naloxone for patients who use heroin, exceed 100 mg morphine equivalents daily, have opioid abuse/dependency, or have had an opioid overdose. Staff training, program monitoring, and staff feedback should be data driven and provided on a regular basis.

Policies and Regulations

There is significant regulatory variability among states.8 Thirty-seven states have successfully amended legal regulations to eliminate legal barriers to naloxone distribution.9,10 Access to naloxone is the main barrier faced by patients and programs, as there are few providers willing to prescribe or distribute naloxone. State emergency medical services (EMS) laws also can restrict which first responders can carry naloxone.11 Liability, real or perceived, is also an important barrier for prescribers, pharmacists, and bystanders. Regulatory solutions include third-party prescribing, standing naloxone orders, collaborative practice agreements, pharmacist-as-prescriber policies, Good Samaritan laws, and increasing EMS/first responder access. Information about these types of legislation and what is present in your state can be found at lawatlas.org/query?dataset=laws-regulating-administration-of-naloxone. (See Figure 1, for a map of states that have legislation preventing prescribers from being criminally liable for prescribing, dispensing, or distributing naloxone to laypeople.)

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Single Page

One Response to “Naloxone Distribution Strategies Needed in Emergency Departments”

April 3, 2016

Larry A. Bedard, MD FACEPACEP has come a long way since 2010 when a wacko doctor from California-me- introduced resolutions to have naloxone over the counter and recommend EPs prescribe naloxone in the ER.

However, ACEP still has a long way to go. Tp deny our role in the opiod epidemic, while frequently blaming other specialities for the epidemic is the wrong approach.