Necrotizing fasciitis is a rapidly progressive inflammatory infection of the fascia, with secondary necrosis of the subcutaneous tissues. The spectrum of presentation is wide, ranging from a benign-appearing rash in a well person to obvious skin necrosis with hemodynamic instability, multi-organ failure, and death. Patients who present early in this spectrum of disease are difficult to diagnose, with an initial misdiagnosis rate of 71.4 percent.1 However, initiation of treatment in these early stages gives patients the greatest chance of survival in this otherwise deadly disease. In this early phase, necrotizing fasciitis can be mistaken for simple cellulitis, and while the skin may appear benign, it is often the tip of the iceberg to what lies beneath.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 37 – No 07 – July 2018The diagnostic difficulty also lies in the fact that there are no lab test results or even imaging that can definitively rule out necrotizing fasciitis. In fact, the diagnosis is a clinical one that can only be confirmed with surgical exploration. Therefore, it is imperative that if you have anything more than the slightest suspicion based on your clinical exam, you consider early consultation with a surgeon for definitive diagnosis and surgical debridement as well as start empiric antibiotics. Lab findings that are suggestive but not diagnostic of necrotizing fasciitis include coagulopathy, hypoalbuminemia, thrombocytopenia, lactic acidosis, creatine phosphokinase elevation, and C-reactive protein (CRP) elevation, which all tend to occur in later stages of disease.1

While clinical decision tools, such as the Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis (LRINEC) score that includes CRP, white blood cell count, hemoglobin, sodium, creatinine, and glucose, might help raise your suspicion for necrotizing fasciitis, validation studies showed that a LRINEC cutoff of six points only had a negative predictive value of 92.5 percent.2,3 While these lab findings and imaging findings of subcutaneous air and fascial thickening on X-ray, CT, and MRI can help support the diagnosis, they should not delay definitive treatment in the operating room in clinically obvious cases and should never override clinical judgment.

Findings on point-of-care ultrasound, which has the advantage of speed over other imaging modalities, may help support the diagnosis but again cannot rule it out.4 The reason that the absence of subcutaneous air on imaging cannot rule out the diagnosis is that one of the two types of necrotizing fasciitis is caused by non–gas-producing bacteria. In fact, imaging findings are often similar to those of cellulitis, with increased soft-tissue thickness and opacity.5 Gas in the soft tissues is seen in only a minority of cases, but if you do see it, your suspicion for necrotizing fasciitis should be significantly raised.

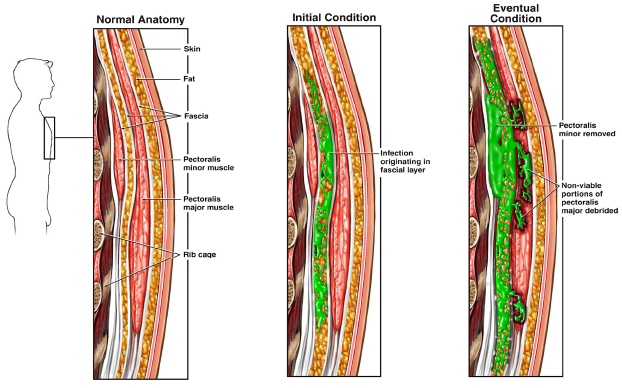

Three cut-sections of the anterior chest wall skin, fat, fascia, pectoralis muscles, and rib bones.

1)Normal chest wall.

2)Origination of infection within the fascial layers.

3)Progression of the infection through those layers and into adjacent tissues.

ILLUSTRATION: Nucleus Medical Media Inc/Alamy Stock PhotO

Clues to Early Detection of Necrotizing Fasciitis

Even though a history of diabetes, immunocompromised state, and recent surgery are often cited as risk factors, necrotizing fasciitis can occur in otherwise healthy patients after a minor traumatic injury.1,6,7

The Infectious Diseases Society of America recommends clinicians look for findings such as persistent severe pain, bullae, skin necrosis or ecchymosis, crepitus from gas in the soft tissues, edema that extends beyond the margin of erythema, cutaneous anesthesia, signs of systemic toxicity, and rapid spread over hours especially during antibiotic therapy.8

Vital signs are vital. Scrutinize them; most patients will have tachycardia and/or tachypnea out of proportion to fever. If you see what appears to be cellulitis on the lower abdomen, examine the perineum for signs of Fournier gangrene.9

Note that while severe pain out of proportion to physical exam findings is suggestive of necrotizing fasciitis, a minority of patients will report little pain and may have a laissez-faire attitude toward their illness, likely due to analgesic effects of local nerve destruction. This same mechanism may account for localized skin hypesthesia that some patients with necrotizing fasciitis may have. The edema of necrotizing fasciitis not only tends to spread beyond the margin of erythema but often has a tense quality, making the skin feel hard or “wooden.”

Palpable crepitance is only present in the gas-producing type of necrotizing fasciitis, and its absence does not rule out the disease for the same reason that imaging cannot rule it out. While rapid progression has been considered a hallmark of this disease, necessitating careful patient monitoring for the development of skin changes and systemic inflammatory response syndrome, subacute necrotizing fasciitis has been described.10

Necrotizing Fasciitis Pitfalls in Diagnosis

Because of the wide spectrum of disease, one of the most common pitfalls is assuming the absence of necrotizing fasciitis in the patient who looks well, rates their pain as mild or absent, is afebrile, or has no palpable crepitus. The other major pitfall in the management of necrotizing fasciitis is doing an extensive workup leading to a delay in surgical debridement in cases where clinical suspicion is high.

The Finger Test for Diagnosis of Necrotizing Fasciitis

In the event that you cannot make a slam-dunk diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis after a careful clinical assessment and you can’t get rapid access to surgical exploration in the operating room or confirmatory imaging, or that the imaging is negative but you still have suspicion for the diagnosis, consider diagnostic confirmation with the finger test.11 After local anesthesia, make a 2- to 3-cm incision in the skin large enough to insert your index finger down to the deep fascia. Lack of bleeding and/or “dishwater pus” (gray-colored fluid) in the wound are very suggestive of necrotizing fasciitis. Gently probe the tissues with your finger down to the deep fascia. If the deep tissues dissect easily with minimal resistance, the finger test is positive for necrotizing fasciitis.

Time-Sensitive Therapy for Suspected Necrotizing Fasciitis

Initial treatment should involve aggressive resuscitation for any signs of hemodynamic instability and early administration of broad-spectrum empiric antibiotics (eg, piperacillin-tazobactam or carbapenem plus vancomycin or linezolid for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus coverage).12 The sooner the necrotic tissue is debrided in the operating room, the better. Time is tissue.

References

- Goh T, Goh LG, Ang CH, et al. Early diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis. Br J Surg. 2014;101(1):e119-125.

- Wong CH, Khin LW, Heng KS, et al. The LRINEC (Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis) score: a tool for distinguishing necrotizing fasciitis from other soft tissue infections. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(7):1535-1541.

- Liao CI, Lee YK, Su YC, et al. Validation of the laboratory risk indicator for necrotizing fasciitis (LRINEC) score for early diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis. Tzu Chi Med J. 2012;24(2):73-76.

- Castleberg E, Jenson N, Dinh VA. Diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis with bedside ultrasound: the STAFF Exam. West J Emerg Med. 2014;15(1):111-113.

- Fugitt JB, Puckett ML, Quigley MM, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis. Radiographics. 2004;24(5):1472-1476.

- Jain S, Nagpure PS, Singh R, et al. Minor trauma triggering cervicofacial necrotizing fasciitis from odontogenic abscess. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2008;1(2):114-118.

- Günel C, Eryılmaz A, Başal Y, et al. Periorbital necrotising fasciitis after minor skin trauma. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2014;2014:723408.

- Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):e10-52. Erratum in: Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(9):1448.

- Faria S, Helman A. Deep tissue infection of the perineum: case report and literature review of Fournier gangrene. Can Fam Physician. 2016;62(5):405-407.

- Childers BJ, Potyondy LD, Nachreiner R, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis: a fourteen-year retrospective study of 163 consecutive patients. Am Surg. 2002;68(2):109-116.

- Andreasen TJ, Green SD, Childers BJ. Massive infectious soft-tissue injury: diagnosis and management of necrotizing fasciitis and purpura fulminans. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107(4):1025-1035.

- Kwak YG, Choi SH, Kim T, et al. Clinical guidelines for the antibiotic treatment for community-acquired skin and soft tissue infection. Infect Chemother. 2017;49(4):301-325.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

3 Responses to “Necrotizing Fasciitis Diagnoses and Therapy”

July 22, 2018

Hirsch KennethI was surprised to see no mention of Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy in the treatment of Necrotizing Fasciitis. I realize that many facilities do not have access to HBO, but if it is readily available HBO can be of great benefit in treating Nec Fasc as an adjunct to surgery and antibiotics.

July 22, 2018

Dan SayersGood overview. I’m in favor of early Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy in addition to all of the above. There is good scientific support for early HBO2 therapy and it is supported by 3rd party payors.

July 30, 2018

Zakiuddin G.Oonwalavery informative article. The ‘finger test’ seems to be a simple confirmatory test. How ever this test may require some exposure to minor surgery, if not performed by a surgeon.