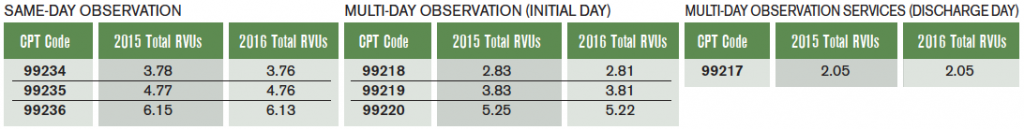

Last November, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) published its 2016 final rule for the Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS). Because observation care is considered an outpatient service, the new rule included important changes to observation billing. Most notably, it retired facility payment observation code APC 8009 and introduced C-APC 8011—the first “C” stands for “comprehensive.”1 Payment increased from $1,234 to $2,174, which is reflective of the new bundled payment for most facility charges previously paid separately (ie, diagnostic imaging, stress testing, and medication infusions). Updates to the professional evaluation and management codes (CPT) for observation care were minor, as illustrated in Table 1.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 35 – No 03 – March 2016

(click for larger image)

Table 1. 2015 and 2016 Observation Professional Total Relative Value Unit (RVU) Values

This major change to bundled facility payments will provide incentives to hospitals to minimize diagnostics and lengths of stay, which favors protocol-driven care and early discharge, features of most emergency medicine–run observation units. For example, in 2007, Ross and colleagues showed that for ED patients with transient ischemic attack randomized to an ED-run observation unit or an inpatient neurology team, the observation unit followed its protocol 97 percent of the time versus 91 percent for the neurology team, with the former having less than half the hospital length of stay and a greater rate of reaching a defined clinical endpoint.2 A 2013 study by Pena and colleagues also found shorter lengths of stay with an ED-run unit versus an open unit run by various services.3 Of note, the new rule does not address long-standing observation-related issues, including lack of coverage for self-administered medications and the vexing requirement for three inpatient nights in the hospital to qualify for a skilled nursing facility benefit.

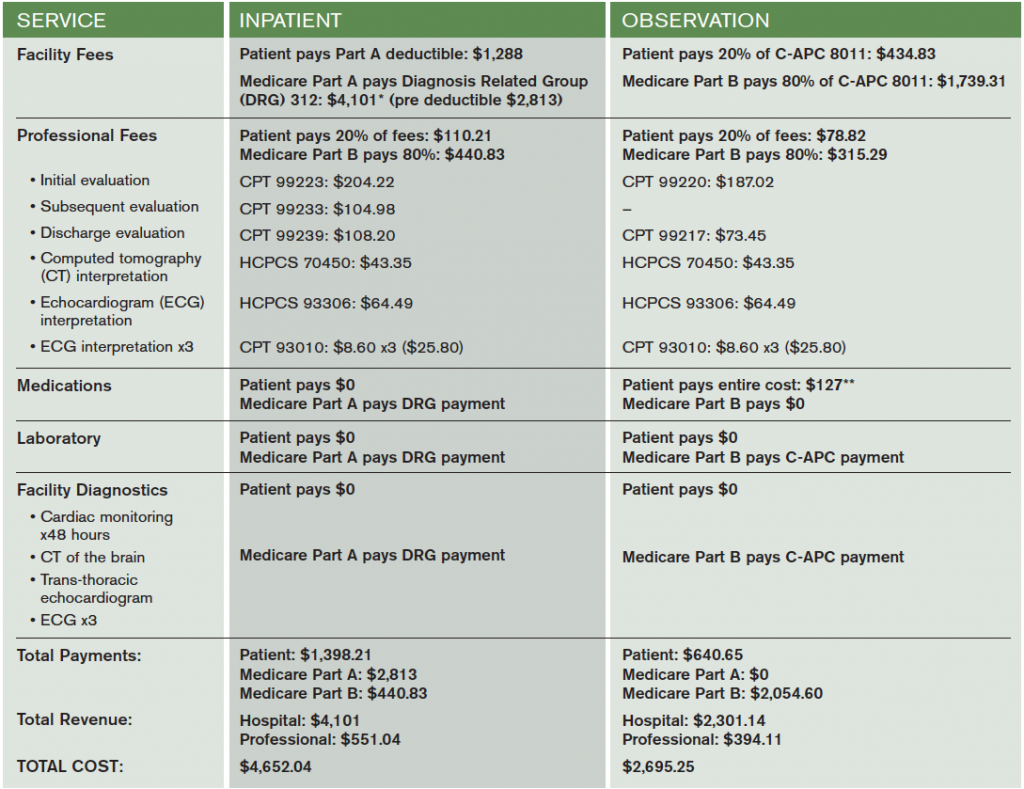

Table 2 compares payments for an observation stay with a short inpatient admission for a patient with traditional Medicare and no second payer, which is the most straightforward example. In this scenario, an elderly patient presents to the ED with syncope and is deemed at intermediate risk. Assuming the patient’s actual hospital visit spanned exactly two midnights, out-of-pocket costs for the observation stay would be around half of the inpatient costs ($640.65 versus $1,398.21), driven largely by the Medicare Part A deductible, a patient expense for inpatient care that should be strongly considered when comparing the expense of observation care to alternatives. Additionally, even in the scenario where a patient begins hospitalization as an observation patient and transitions to inpatient care (an expected outcome in about 20 percent of cases), the facility charges roll into Part A and the observation facility coinsurance liability disappears.4 The only additional costs to the patient would be the self-administered medication costs and professional fee coinsurance during the brief observation stay, which is typically a small fraction of the facility payment.

(click for larger image)

Table 2. Sample Medicare Fees and Payments for a Typical Hospitalization for Syncope

These calculations are for traditional fee-for-service Medicare without a secondary payer. Part B payments assume the $166 annual deductible has already been paid. Part A payments assume the patient has not paid for any qualifying Part A services in the prior 60 days.

*DRG payment calculated as mean unadjusted 2013 Medicare payment amount.

**Average out-of-pocket medication costs based on 2013 Office of the Inspector General Report.5

The best data available on Medicare beneficiary out-of-pocket expenses arise from a 2013 report from the Office of the Inspector General, which shows that the patient expense for an observation stay was less than the expense for a short inpatient stay 94 percent of the time.5 Additionally, the percentage of patients caught in the scenario where they were hospitalized for three or more nights but didn’t have three inpatient overnights (ie, start in observation, then transition to inpatient for a couple more days) and needed subsequent skilled nursing facility care that Medicare did not pay for was 0.6 percent of all observation visits.5 In the lay press, stories from this small fraction of visits make for very compelling news, and as a result, the headlines featuring these visits highlight a real but exceedingly rare consequence of observation care.6

In conclusion, Medicare’s shift to a bundled facility payment this year creates an incentive to use evidence-based protocols for observation care while also effectively capping the patient out-of-pocket costs for observation facility charges. The new rule still does not address previous patient financial issues, such as shifting the burden of self-administered medications onto patients (or providers) or the lack of time counting toward a skilled nursing facility benefit for nights spent in the hospital while in observation status. However, this new rule helps to clarify and cap the patient expense for an observation visit, a seemingly positive development in observation care.

Dr. Baugh is the medical director of emergency department operations at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston and chairs the ACEP Observation Medicine Section.

Dr. Granovsky is president of LogixHealth, a national ED coding and billing company, as well as chair of the ACEP Reimbursement Committee.

References

- Hospital outpatient prospective payment—final rule with comment period and final CY2016 payment rates. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. Accessed Dec. 29, 2015.

- Ross MA, Compton S, Medado P, et al. An emergency department diagnostic protocol for patients with transient ischemic attack: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50(2):109-119.

- Pena M, Fox J, Southall A. Effect on efficiency and cost-effectiveness when an observation unit is managed as a closed unit vs an open unit. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:1042-1046.

- Baugh CW, Venkatesh AK, Bohan JS. Emergency department observation units: a clinical and financial benefit for hospitals. Health Care Manage Rev. 2011;36(1):28-37.

- Hospitals‘ use of observation stays and short inpatient stays for Medicare beneficiaries, OEI-02-12-00040[PDF]. Office of the Inspector General Web site. Accessed Feb. 12, 2016.

- Span P. In the hospital, but not really a patient. The New York Times. Accessed Oct. 21, 2015.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “New CMS Rules Introduce Bundled Payments for Observation Care”