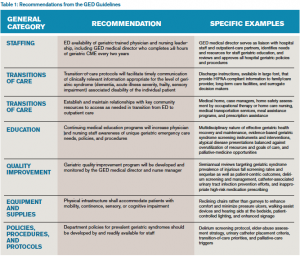

The GED Guidelines consist of 40 specific recommendations in six general categories: staffing, transitions of care, education, quality improvement, equipment/supplies, and policies/procedures/protocols. Staffing includes recommendations for the medical director and nurse manager and accessibility to specialist ancillary services. Transitions of care include discharge processes and large-font instructions, as well as appropriate collaboration with home health services and home safety assessments. Nurse and clinical provider education focuses on contemporary, research-based geriatric-specific material. The quality improvement recommendations provide an exemplar spreadsheet of pertinent and prevalent geriatric emergency care indicators to monitor, including the prevalence of injurious falls and documentation of fall risk assessment. The equipment and supplies section describes potential physical structure enhancements like the use of reclining chairs and pressure redistributing foam mattresses to improve comfort and reduce the incidence of pressure ulcers. Finally, a variety of policies, procedures, and protocols are provided to facilitate screening older adults to identify the subset who are at increased risk for post-ED adverse outcomes, as well as validated, ED feasible screening instruments for geriatric syndromes such as delirium, polypharmacy, falls, and dementia. See Table 1 for more details about specific GED recommendations that should provide further clarity about the content of the GED Guidelines.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 33 – No 03 – March 2014The Present and Future Plans for the GED Guidelines

These guidelines represent a two-year effort from multiple organizations and individuals committed to optimizing the emergency care delivery model for geriatrics. We believe that the geriatric ED patient represents the “canary in the coal mine” for our health care system. If we can successfully navigate the diagnostic, therapeutic, disposition, and financial challenges that this potentially vulnerable population presents to 21st-century medicine, then all age groups will benefit from a reliable, available, compassionate, and efficient emergency care system. We fully recognize that the GED Guidelines are a beginning and not an end. The authors have defined a plan that includes dissemination, implementation, adaptation, and refinement. The empiric basis for the recommendations rests upon minimal research evidence. To move forward, geriatric emergency medicine needs sustainable funding opportunities to: 1) enhance the evidentiary basis of these protocols; 2) determine if following these recommendations does, in fact, improve the process and quality of care delivered; 3) determine if the recommendations improve health care outcomes for older adults and their caregivers; and 4) support the growth and evolution of future geriatric emergency medicine leaders.

One immediate next step is to prioritize, in a systematic and transparent way, the 40 recommendations into essential and nonessential domains so hospital administrators, payers, and research funders can develop a systematic approach to local implementation. For example, routinely screening for delirium using validated instruments has profound implications on ED disposition and management decisions as opposed to infrastructural changes to lighting, floor material, and wall colors. The prioritization process will assess the relative potential benefits and potential harms associated with each recommendation in providing a weighted list from most to least important. Another step is to raise GED Guidelines awareness among emergency medicine clinicians, hospital administrators, patient advocacy leaders, and patients. The GED Guidelines group is also developing a “Geriatric Emergency Department Boot Camp” program, in which geriatric emergency medicine leaders will bring the recommendations to those interested, including a toolbox of resources, pragmatic examples from their own institutions, and mentorship. The benefit of the boot camp concept is that hospitals interested in “geriatricizing” their ED need not travel to learn more about these implementation recommendations, and essential interdisciplinary members (i.e., social workers, case managers, pharmacists, hospital administrators, and payers) can also participate via this boot camp idea. The intent is for participants in the boot camps to devise local and regional needs-based quality-improvement projects, which the boot camp faculty can assist; one-year outcomes will be assessed. The boot camp concept also provides a tangible test tube to evaluate the feasibility, acceptability, and barriers to implementing existing GED Guideline recommendations.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

2 Responses to “New Guidelines Enhance Care Standards for Elderly Patients in the ED”

November 23, 2014

Aslaner: Geriartrik Acil Servis Kılavuzu | Acilci.Net: Acil Tıp Eğitimi için EKG, Kılavuz, Video ve Sunumlar[…] https://www.acepnow.com/article/new-guidelines-enhance-care-standards-elderly-patients-ed/. […]

August 13, 2015

Elderly Patients Want to Be in Control of Their Health Information - ACEP Now[…] Elderly patients may be willing to let family members access their medical records and make decisions on their behalf, but they also want to retain granular control of their health information, a study suggests. […]