Members of ACEP’s Emergency Medicine Practice Committee, along with the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, created a tool for quick reference and application to aid the emergency medicine provider caring for a post–bariatric surgery patient.

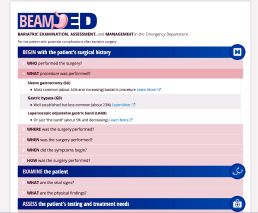

The BEAM-ED tool, which can be found on the ACEP website at www.acep.org/beam, was designed for easy access and is structured in a history, physical exam, diagnostic, and treatment format.

The first step centers on the patient’s history. The design of the information facilitates an understanding of several possible conditions following the most common bariatric surgical procedures. Since the practicing emergency physician often acquires, reviews, and processes data while performing tasks simultaneously, this format allows for a targeted yet comprehensive survey of the evaluation of the post–bariatric surgery patient. By opening each of these sections (eg, who, what, where, and how), one can ascertain pertinent information that will establish a framework to initiate the diagnostic evaluation. I particularly like the “what” section (see Figure 1), as it gives the user a visual overview and a brief description of the procedure performed on the patient. This allows one to comprehend the most common anatomical modifications performed, from the more traditional gastric bypass (GB) to the more common sleeve gastrectomy (SG).

Figure 2: Internal hernia with small bowel obstruction.

ACEP

The other significant historical component centers on determining when the surgery occurred. Patients who present fewer than 30 days from the onset of their surgery are more likely to have bleeding complications, wound infections, or an anastomotic leak. Those patients who present after 30 days are more likely to have an abscess, intestinal obstruction, internal hernia (see Figure 2), or nutritional concerns. What remains constant in our approach are the ABCs and the need to determine which patients are stable and which need emergent intervention. The diagnostic study of choice remains CT scan with oral and IV contrast. For post-bariatric surgery patients, an immediate CT scan after drinking one or two cups of contrast will suffice.

Once the etiology of the patient’s symptoms has been elucidated, the diagnostic findings are further subdivided into what to anticipate after the various surgical procedures. Furthermore, there is an instructional video showing how to deflate a gastric band. In addition to being an efficient clinical reference for the practitioner in the emergency department, the information could be used to generate bariatric order sets for an electronic medical record. The information on this site will be updated periodically to provide the emergency department clinician easy access to the most current recommendations for the post–bariatric surgery patient.

Pages: 1 2 | Single Page

No Responses to “Online Clinical Tool for Post–Bariatric Surgery Patients Could Improve Management”