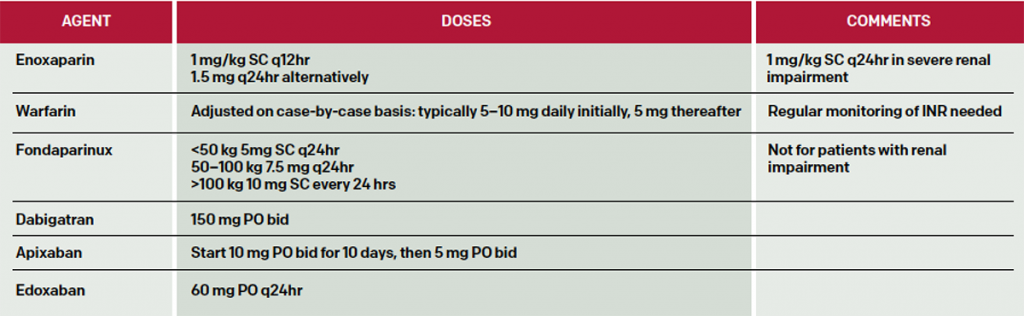

As there are currently multiple pharmacologic options for anticoagulation (see Table 1), it is important for emergency physicians to be well-informed to choose the best option for their patients. Current options include the following agents: LMWH, enoxaparin, dalteparin, tinzaparin, nadroparin, fondaparinux, warfarin, and the novel anticoagulants (NOACs) dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban. If the patient is prescribed warfarin, then therapeutic dosages of an unfractionated heparin should be given for five days until the international normalized ratio (INR) is therapeutic. Starting warfarin at 10 mg per day on days one and two has been recommended as safe and able to achieve a therapeutic INR more rapidly than 5 mg daily.1,2 Regular monitoring of the INR for patients taking warfarin is necessary due to wide individual genetic differences to warfarin response as well as to the wide number of medication interactions with warfarin. NOACs are attractive alternatives due to their oral route of administration, quick and predictable onset of action, and avoidance of repeat blood draws to monitor coagulation parameters. Studies suggest that NOACs are non-inferior to warfarin with regard to DVT complications and risk of bleeding.7 NOACs are renally excreted but have not been well-studied in patients with creatinine clearance levels less than 30 µmol/L.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 35 – No 08 – August 2016Suggested doses of anticoagulants are listed in Table 2. Here are short summaries of selected agents.

LMWHs are preferred agents for treatment of DVT in pregnancy, DVT in cancer patients, and patients with procoagulant disorders.2 Enoxaparin (Lovenox) is administered at 1 mg subcutaneously (SC) every 12 hours or 1.5 mg/kg daily. Dalteparin (Fragmin) is typically dosed at 200 units/kg SC daily for one month, then 150 units/kg Sc thereafter. LMWHs are renally excreted, and dosing must be modified for renal insufficiency.

(click for larger image)

Table 2: Selected Dosing of Anticoagulants in Patients with DVT. Note that limited data are available for morbidly obese patients, while patients with mass less than 57 kg for men and less than 45 kg for women are at increased risk of bleeding with heparins.1,2

While generally safe, a subset of patients will develop life-threatening bleeding complications while anticoagulated. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), with its risk of extensive thrombotic complications, is less likely to occur with LMWHs than with unfractionated heparin but still mandates discontinuation of these agents, including unfractionated heparin, for the rest of the patient’s life.

The limitations of warfarin prompted the development of NOACs, which produce a predictable anticoagulant response without requiring routine monitoring.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Single Page

4 Responses to “Options, Approaches to Outpatient Treatment of Deep Vein Thrombosis for Emergency Physicians”

August 24, 2016

Sunjeev Konduru, MS, PharmD, BCPSThe dosing of apixaban in this article does not match the FDA prescribing information, which states give 10mg twice a day for 7 days, followed by 5mg twice a day. This dose of Eliquis was studied in the AMPLIFY trial for 6 months versus lovenox and warfarin in patients with symptomatic PE or proximal DVT.

Edoxaban also required initial parenteral anticoagulation for 5 to 10 days, similar to dabigatran.

Thank you.

August 28, 2016

jakeYou correctly point out dabigatran as a direct thrombin inhibitor in the text of the article, however, in the table it is incorrectly listed as a Xa inhibitor.

August 30, 2016

Dawn Antoline-WangThank you, the table has been updated to reflect this correction.

August 29, 2016

Soumya Ganapathy MDGreat article. When treating DVTs and PEs as an outpatient, patient education is paramount. Patient and their families can often feel overwhelmed. ACEP has a program called knowbloodclots.com, it is a great resource for patient education on DVTs and PEs. They have nice videos like what to expect with DVT and PE treatment as well as warning videos on the risk of bleeding. They also have a free texting program that sends reminders and educational links to patients.