Note: This article is our CME Now offering for the February 2023 issue. After you read it, visit ACEP’s Online Learning Center to earn CME credit.

Case

A young male is brought to the emergency department (ED) via EMS after sustaining a gunshot wound. The trauma team is activated. The patient is hemodynamically stable and has an intact primary survey. On secondary survey, there is a perforating wound. Across from the wound is a bulge in the skin with a palpable foreign body, presumably a bullet. Radiographic imaging shows no serious vascular or bony injury, and confirms the presence of a superficial, bullet-shaped radiopaque foreign body as noted on exam. Given its position, the trauma team decides to remove the bullet at the bedside. You then hear the surgical resident tell the nurse, “Get me a scalpel, tray, and a metal basin. I love hearing the bullet drop into the basin.” How do you respond to this request?

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 42 – No 02 – February 2023Discussion

Firearm injuries are increasingly common in the United States. In 2020, there were over 45,222 firearm-related deaths. Many more Americans were injured by firearms with more than 70 percent of them were firearm-related assaults.1 Following a gunshot wound, there are a few possible outcomes: the patient dies at the scene, the patient is transported to the hospital and dies either in the ED, operating room, or at some point after hospital admission. For patients who do not survive, their forensic needs are met by the coroner or medical examiner. Other patients following a gunshot would arrive to the ED and undergo treatment and evaluation, and are either admitted to the hospital or discharged. Ultimately, those who make it to the hospital and survive rely on emergency physicians and ED personnel to help meet their forensic needs. Our primary goal remains resuscitation and stabilization, however, we should be cognizant of the forensic needs.

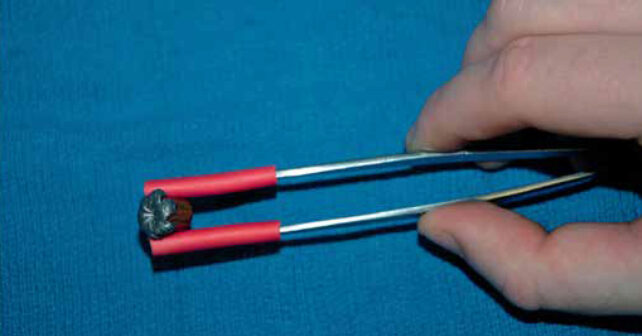

FIGURE A: Because bullets are soft and malleable, use of metallic surgical

instruments like forceps to grasp the bullet can impart marks from the instrument

into the bullet. (Click to enlarge.)

One aspect to consider is how to handle evidence. Ammunition, or a cartridge, is the object that is loaded into a firearm. It consists of a cartridge case which holds the bullet, a primer, and powder. Upon firing the weapon, the bullet becomes the projectile. Cartridges are commonly made of brass (copper and zinc). Bullets come in a variety of shapes, sizes, and compositions. Bullets are often made of copper, steel, and lead (though lead is becoming less common). Copper and lead are soft and malleable so they can conform to the barrel of the weapon, which has spiral impressions called lands and grooves. Traveling along the barrel imparts ballistic markings onto the bullet that experts can use to match it to the weapon and other possible casings.2,3

How we handle bullets in the ED can affect the ballistic analysis. Because bullets are soft and malleable, use of metallic surgical instruments like forceps to grasp the bullet can impart marks from the instrument into the bullet (Figure A). These marks can disrupt the ballistic markings and make comparisons and weapon matching impossible. Furthermore, dropping the bullet into a metal basin can also alter these ballistic markings and have similar consequences. There have been reports of physicians using a metallic instrument to mark the bullet with their initials or a symbol so they can identify it if asked in court. This can also ruin, obscure, or alter ballistic markings and should not be used.

FIGURE B(LEFT): If metallic instruments are to be used, they can be modified with rubber or silicone tubing over the tips (red-rubber catheters or Suture Booties) to prevent them from damaging the bullet.

So, what should be done to remove and handle bullet evidence?4 First of all, whenever possible use instruments made of plastic to retrieve and handle bullets. Often these may not be available or as useful as metallic instruments. If metallic instruments are to be used, they can be modified with rubber or silicone tubing over the tips (red-rubber catheters or Suture Booties) to prevent them from damaging the bullet (Figure B). Use minimal pressure when handling the bullet and if able, do not engage the clamping mechanism of the instrument. Next, never drop the bullet into a metal basin; use a plastic basin. If only a metal basin is available, line it with surgical towels and create a divot to gently place the bullet into until it can be packaged. And of course, do not place your own marks on the bullet and minimize any handling of it. You do not need clean the bullet, but you can gently remove any large pieces of tissue.

The bullet then should be packaged for transfer to law enforcement. The best way to do that is to place it a coin envelope. You can wrap it in gauze first for added protection. As an alternative, a sterile plastic specimen cup can be used. It should be lined with gauze as well in order to protect the bullet and prevent it from moving around. Whichever packaging is used, it should then be labeled with the patient’s name, date and time, and the name of the person who collected and/or packaged the evidence. Next, a chain of custody form should be used or chart notation should be made detailing what was done with the evidence. At a minimum, the name of the accepting officer and their badge number, law enforcement agency, name of the person turning over the evidence, date and time, and the signatures of both persons should be documented. A copy should remain in the chart and another copy should be sent with the evidence.

Case Resolution

You politely explain to the surgical resident the nature of bullets, and proper evidence collection procedures. They thank you for helping them out and you offer to stay and help show them how to package the evidence. The bullet is removed with a plastic forceps and placed in a plastic basin until you and the resident package it in a specimen cup, label it, and complete the chain of custody form for law enforcement.

Dr. Rozzi is an emergency physician, secretary of the Forensic Examiner Team at WellSpan York Hospital in York, Pennsylvania, and chair of the Forensic Section of ACEP.

Dr. Rozzi is an emergency physician, secretary of the Forensic Examiner Team at WellSpan York Hospital in York, Pennsylvania, and chair of the Forensic Section of ACEP.

Dr. Riviello is chair and professor of emergency medicine at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

Dr. Riviello is chair and professor of emergency medicine at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fast Facts: Firearms injury prevention. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/firearms/fastfact.html. Accessed May 4, 2022.

- BiMaio VJM. Gunshot wounds: practical aspects of firearms, ballistics, and forensic techniques. Gunshot Wounds. https://cdn.preterhuman.net/texts/law/forensics/Gunshot%20Wounds%20-%20Practical%20Aspects%20of%20Firearms%20Ballistics%20and%20Forensic%20Techn.%202nd%20ed.%20-%20V.%20DiMaio.pdf. Published 2010. Accessed January 25, 2023.

- Sing RF, Sullivan JM Gunshot/shotgun injuries. In: Riviello RJ (ed). Manual of forensic emergency medicine: a guide for clinicians, Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett, 2010, 2010, pp. 87–97.

- Masteller MA, Prahlow A, Walsh MM, Thomas SG, Wolfenbarger R, Prahlow JA. Proper handling of bullet evidence in trauma patients. Trauma. 2014;16(3):189-194.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Ping Ping Ping Goes the Bullet—or Should It?”