Explore This Issue

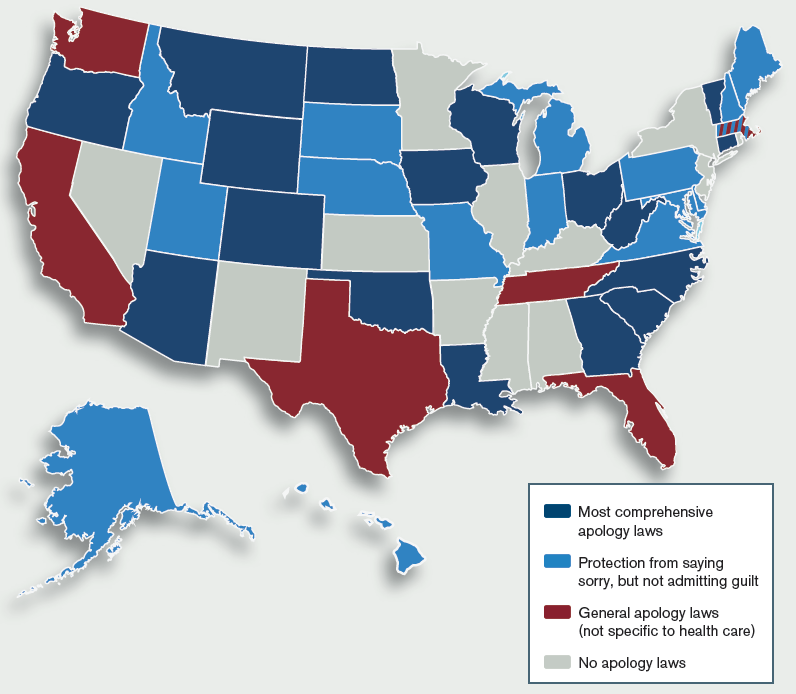

ACEP Now: Vol 40 – No 11 – November 2021Figure 1: “I’m Sorry” Laws by State. Chris Whissen & Shuttestock.com

I have always strived to apologize when I thought someone was harmed by my actions. This is a lesson taught to children from their earliest days. When children begin to understand right from wrong, a parent will frequently ask the child to say, “I’m sorry,” as part of this developmental process. As children grow and mature, the hope is that they will initiate this behavior on their own. As adults, we begin to say we are sorry for many events, such as loss of a loved one or other tragedies in people’s lives.

This process and basic human quality are unfortunately flipped on their head in the medical world and in the emergency departments in which we all work.

When in the emergency department providing medical care, our human tendency to say we are sorry for tragic events is frequently restrained by the fear of litigation. We ask ourselves, “If I say I am sorry, will they think I am admitting guilt and sue me? Can they use this apology against me in court? Will hospital administration get mad at me for saying I’m sorry?” The questions and anxiety surrounding this can be paralyzing and prevent us from doing what is very likely the right thing. Fortunately, most states have enacted laws to protect the physician saying, “I’m sorry.” They have variable protection, and knowing your state law is crucial. Also, there are institutions such as the Veterans Administration in Lexington, Kentucky, and University of Michigan that have full disclosure of error programs that involve apologizing for the error, root cause analysis on how it happened to prevent future errors, and offer of settlement. However, not all agree that apology laws make a significant decrease in litigation, and some say they can actually increase the incentive to sue when the patients hear the apology and think the clinician has committed malpractice.1,2

Medical malpractice rules are almost entirely based on state law because the litigation is done in state courts unless a federal statute is violated. Knowing the laws and practice patterns of your state(s) of practice is critical to understanding your protection around apology laws. The state laws really fall into four general categories: total protection, partial protection, general apology statutes, and no protection.3 We will explore the differences in these categories and discuss the relevant clinical implications of them. Please remember to consult local legal experts for the details on how the written law is applied in your state jurisdiction.

“I’m Sorry” Laws by State

Those who live in Arizona, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Iowa, Louisiana, Montana, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Carolina, Vermont, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming as well as Washington, D.C., are covered by the most comprehensive apology laws (see Figure 1). I practice primarily in the State of Ohio, where Ohio Revised Code Section 2317.43 reads:

(1) In any civil action brought by an alleged victim of an unanticipated outcome of medical care … any and all statements, affirmations, gestures, or conduct expressing apology, sympathy, commiseration, condolence, compassion, error, fault, or a general sense of benevolence that are made by a health care provider … that relate to the discomfort, pain, suffering, injury, or death of the alleged victim as the result of the unanticipated outcome of medical care are inadmissible as evidence of an admission of liability or as evidence of an admission against interest. [emphasis added]

Fortunately, with this broad protection, practitioners in Ohio can apologize with little fear that their words will be used against them. I have said I am sorry to many families over the years for unanticipated medical tragedies; to this day, I still feel it was the right thing to do. As proponents of the University of Michigan model would say, an open and honest discussion after these events has been shown to decrease the frustration felt by those affected; decrease the frequency of litigation; and, when harmed, decrease the settlement amounts.

The partial protection states include Alaska, Delaware, Hawaii, Idaho, Indiana, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, Maryland, Nebraska, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Utah and Virginia. If you practice in these areas, you have protection from saying sorry but not if you admit guilt. If you admit wrongdoing, those statements can be admissible in court. The Michigan law, MCL Section 600.2155, reads:

A statement, writing, or action that expresses sympathy, compassion, commiseration, or a general sense of benevolence relating to the pain, suffering, or death of an individual … is inadmissible as evidence of an admission of liability in an action for medical malpractice.

This section does not apply to a statement of fault, negligence, or culpable conduct … [emphasis added]

If I was a practitioner in Michigan, I could still say I am sorry for the unanticipated medical outcome, but if I also said, “It was my fault,” that could be used against me in any civil legal proceedings. The plaintiff’s attorney would question me around the admission of fault in a deposition and then at trial if needed. The University of Michigan exists in this legal system and feels its open and honest approach helps with families’ need for transparency and the need for information on what happened to their loved one. There is some debate, however, on whether the University of Michigan’s strong performance and quality improvement program, its approach to harm, or both have decreased the actual number of cases litigated.4

Some states take a more general approach to apology laws; those include California, Florida, Massachusetts, Tennessee, Texas, and Washington. These states are trying to protect the human need to apologize in much broader circumstances outside of health care. The Texas law, Section 18.061, reads, in part:

Communications of Sympathy (a) A court in a civil action may not admit a communication that: (1) expresses sympathy or a general sense of benevolence relating to the pain, suffering, or death of an individual in an accident, (2) is made to the individual or a person related to the individual … a communication, including an excited utterance … which includes … statements concerning negligence … pertaining to an accident or event, is admissible to prove liability of the communicator. [emphasis added]

Notice that the act of apology or expression of sympathy after an accident is protected here, but any admission of fault or negligence is not protected and admissible to prove liability. California’s law and wording are very similar to Texas’s; however, California specifically excludes the admissibility of any statement related to fault in an accident. Remember, these laws are general apology laws, not specific for health care, and their applicability to health care accidents will vary by state.

There are 12 states left that do not have formal apology laws: Alabama, Arkansas, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, Minnesota, Mississippi, New Jersey, Nevada, New Mexico, New York, and Rhode Island. If you practice in these states, there is no partial or full protection for apologies and admissions of fault. This lack of protection could lead to decreased communication between patients, families, doctors, and health systems. Families and patients may be compelled to seek legal counsel more often and initiate litigation to get the answers they need for their questions. Without adequate protection in these states, it would be very challenging, if not impossible, to follow the ACEP Policy Statement on Disclosure of Medical Errors.3 It states, in part:

If, after a careful review of all available relevant information, emergency physicians determine that a medical error has occurred during their care of a patient in the ED, they or appropriate designee should inform the patient in a timely manner … and provide information about the error and its consequences following institutional and practice group policies and considering applicable state statures on this subject.

Do “I’m Sorry” Laws Offer Enough Protection?

As mentioned above, the Veterans Administration and the University of Michigan have instituted self-disclosure policies that involve an explanation if an error occurred, an apology, a settlement offer, and a systemic approach of quality improvement to prevent that error from happening again in the future. Both have stated that this approach has decreased the number of legal claims against the institutions. It seems that this type of system should be protected by all state laws and be the standard for medical error disclosure and the quality improvement needed so that an error never happens again. However, an article in the Stanford Law Review states, “Once a patient has been made aware that the physician has committed a medical error, the patient’s incentive to pursue a claim may increase even though the apology itself cannot be introduced as evidence.”4 Similarly, an article in the Lewis and Clark Law Review states, “[Their research] shows that while apology laws may reduce the frequency and size of malpractice claims as intended, they may also have a perverse effect on patients’ propensity to litigate … an apology could alert the patient to that malpractice and encourage the filing of a claim.”5

As a practicing physician out of residency for more than 25 years, I must admit it feels good to be able to apologize to families when an unexpected tragedy occurs during the course of medical care, even when I don’t feel I am at fault. Being able to do that in my professional life mirrors what I strive to do in my private life and creates less internal conflict for me in these difficult situations. It seems unclear that apology and offers of settlement alone decrease litigation, but coupled with a system-based strong root-cause analysis and quality improvement program driving harm to zero, it can decrease all causes of system errors and malpractice. Plus-circle

Dr. Naber is associate chief medical officer at UC Health, Drake Hospital in Cincinnati and associate professor of emergency medicine and medical director of UR/CDI at University of Cincinnati Medical Center.

Dr. Naber is associate chief medical officer at UC Health, Drake Hospital in Cincinnati and associate professor of emergency medicine and medical director of UR/CDI at University of Cincinnati Medical Center.

References

- Smith ML. I’m sorry laws: what’s a respiratory therapist’s apology worth? The Health Law Firm website.. Accessed Oct. 8, 2021.

- Hicks J, McCray C. When and where to say “I’m sorry.” CLM Magazine website. Accessed Oct. 8, 2021.

- Disclosure of Medical Errors. ACEP website. Accessed Oct. 15, 2021.

- McMichael BJ, Van Horn RL, Viscusi WK. “Sorry” is never enough: how state apology laws fail to reduce medical malpractice liability risk. Stanford Law Rev. 2019;71(2):341-409.

- McMichael BJ. The failure of sorry: an empirical evaluation of apology laws, health care, and medical malpractice. Lewis & Clark L Rev. 2018;22(4):1199-1281.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Several States Protect Physicians Who Apologize, But Be Careful”