Key Results

The trial enrolled 1,046 patients and used a modified intention-to-treat analysis. The average patient age was the early 60s and more than 50 percent had metastatic disease, with 30 percent having recurrent cancer. Edoxaban was found to be noninferior to LMWH for the primary outcome of recurrent VTE or major bleeding.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 38 – No 01 – January 2019- Primary Outcome: Recurrent VTE or major bleeding.

- 12.8 percent versus 13.5 percent; HR, 0.97 (95% CI, 0.70 to 1.36; P=0.006 for non-inferiority)

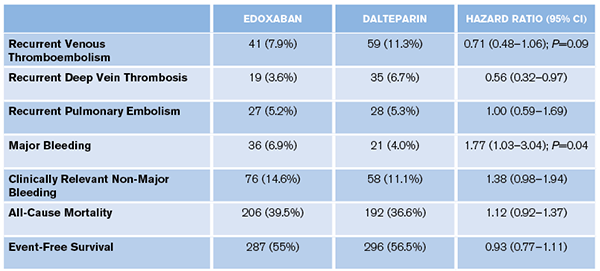

- Secondary Outcomes: See Table 1.

Evidence-Based Medicine Commentary

- Lack of Blinding: Patients were aware of group allocation, while the outcome assessors for major bleeding were blinded. It is unclear whether the lack of patient blinding would have affected the results. The researchers could have minimized this bias by having placebo pills and SQ injections as controls.

- Primary Outcome: The researchers created a composite outcome of efficacy (VTE recurrence) and safety (major bleed). Why not just have one primary outcome? Would the patients value the lower VTE rate with edoxaban (7.9 percent versus 11.3 percent) more or the lower major bleed rate (6.9 percent versus 4.0 percent) with LMWH? There was no statistical difference in all-cause mortality or event-free survival. They could have asked the patients a priori what they felt the most important outcome was, powered the study for this outcome, and considered all the rest as secondary outcomes.

- Changes to Endpoint and Time Frame: The original trial design had co-primary outcomes for VTE recurrence and clinically relevant bleeding. This was changed to a composite outcome of VTE recurrence and major bleeding event.The researchers also extended the time frame from six to 12 months. The original primary outcomes at six months are not listed in the publication and can only be found in the supplementary appendix.

These results showed noninferiority of edoxaban compared to LMWH for recurrent VTE (6.5 percent versus 8.8 percent; HR 0.75 [95% CI, 0.48–1.17]), but an increase in clinically relevant bleeds (15.9 percent versus 10.7 percent; HR 1.54 [95% CI, 1.10–2.16]). There was no difference in all-cause mortality or event-free survival.

- Noninferiority: This trial was designed to see if oral edoxaban was not worse (noninferior) than LMWH. What about patient satisfaction of an oral medication compared to a daily injection? There was also no mention of cost, which may play a role in determining noninferiority.

- Conflicts of Interest: The authors reported multiple conflicts of interest, and the trial was sponsored by the maker of edoxaban. The pharmaceutical company, in collaboration with the coordinating committee, was responsible for the trial design, protocol, and oversight, as well as collection and maintenance of the data. It also performed all the statistical analysis in collaboration with the writing committee. This does not make the data wrong but should make us more skeptical.

Bottom Line

It may be reasonable to discuss oral edoxaban with patients as a potential treatment for cancer-associated VTE. However, the decision should probably be left up to the patient and their oncologist.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

One Response to “Should You Use Direct Oral Anticoagulants for Cancer-Associated VTE?”

January 20, 2019

Gregg ChesneyThanks for this review! I had this exact debate last week (but enoxaparin vs rivaroxaban) with our ED pharmacist, the patient’s oncologist and his general surgeon for a patient with an acute DVT 2 weeks post-op from a resection of a colonic adenocarcinoma. I hadn’t seen the new article in the NEJM yet, and the 2016 ACCP VTE guidelines are still recommending LMWH. I had originally ordered enoxaparin but the oncologist decided he wanted to manage him on rivaroxaban, citing new data that DOACs are noninferior in these patients, which I hadn’t had a chance to look for yet, so thanks for filling me in!