The Case

A 73-year-old man currently undergoing chemotherapy for colon cancer presents to the emergency department with a swollen right leg. His vital signs are all stable, and his leg does not look like it has cellulitis. The ultrasound confirms your suspicion of a deep-vein thrombosis (DVT). The patient is being prepared for outpatient management, but does not want to be on injections for the next six to 12 months. He asks if there are any other treatments besides low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH).

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 38 – No 01 – January 2019Background

Cancer increases the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE). Patients with cancer can be difficult to manage due to the higher risk of bleeding and the higher rate of thrombosis recurrence. The CLOT trial established LMWH as the standard therapy for symptomatic and asymptomatic VTE.1

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) like rivaroxaban have been shown to be effective treatments for VTE without causing increased bleeding complication rates in non-cancer patients. A trial by Bean et al suggested it was safe and effective to dry start DOACs (no LMWH needed) in certain patients with VTE.2

Although DOACs are frequently used in the treatment of cancer-associated VTE, there is little evidence to support this practice. The SELECT-D trial was a small open-label pilot trial looking at the use of rivaroxaban. It showed a lower hazard ratio (HR) for VTE with wide confidence intervals and a higher clinically relevant non-major bleeding rate.3

Clinical Question

In cancer-associated VTE, is edoxaban noninferior to LMWH?

Reference

Raskob GE, van Es N, Verhamme P, et al. Edoxaban for the treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(7):615-624.

- Population: Adult patients with active cancer or cancer diagnosed within the previous two years with acute symptomatic or asymptomatic VTE.

- Exclusions: See the article’s supplementary appendix.

- Intervention: LMWH for five days followed by oral edoxaban 60 mg daily for at least six months.

- Comparison: Subcutaneous (SQ) dalteparin 200 IU/kg daily (maximum 18,000 IU) for one month followed by 150 IU/kg daily for at least five months.

- Outcome:

- Primary: Composite of recurrent VTE or major bleeding during 12-month follow-up.

- Secondary: Clinically relevant non-major bleeding (CRNB), event-free survival, VTE-related death, all-cause mortality, recurrent DVT, recurrent pulmonary embolism. (The complete list is in the article’s supplementary appendix.)

Authors’ Conclusions

“Oral edoxaban was noninferior to subcutaneous dalteparin with respect to the composite outcome of recurrent venous thromboembolism or major bleeding. The rate of recurrent venous thromboembolism was lower but the rate of major bleeding was higher with edoxaban than with dalteparin.”

Key Results

The trial enrolled 1,046 patients and used a modified intention-to-treat analysis. The average patient age was the early 60s and more than 50 percent had metastatic disease, with 30 percent having recurrent cancer. Edoxaban was found to be noninferior to LMWH for the primary outcome of recurrent VTE or major bleeding.

- Primary Outcome: Recurrent VTE or major bleeding.

- 12.8 percent versus 13.5 percent; HR, 0.97 (95% CI, 0.70 to 1.36; P=0.006 for non-inferiority)

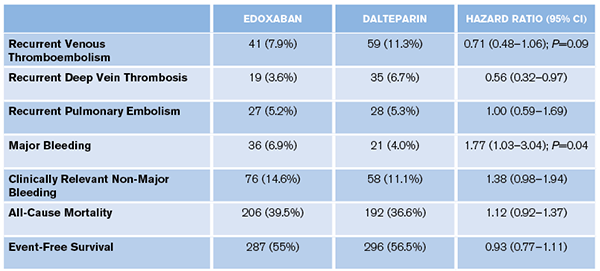

- Secondary Outcomes: See Table 1.

Evidence-Based Medicine Commentary

- Lack of Blinding: Patients were aware of group allocation, while the outcome assessors for major bleeding were blinded. It is unclear whether the lack of patient blinding would have affected the results. The researchers could have minimized this bias by having placebo pills and SQ injections as controls.

- Primary Outcome: The researchers created a composite outcome of efficacy (VTE recurrence) and safety (major bleed). Why not just have one primary outcome? Would the patients value the lower VTE rate with edoxaban (7.9 percent versus 11.3 percent) more or the lower major bleed rate (6.9 percent versus 4.0 percent) with LMWH? There was no statistical difference in all-cause mortality or event-free survival. They could have asked the patients a priori what they felt the most important outcome was, powered the study for this outcome, and considered all the rest as secondary outcomes.

- Changes to Endpoint and Time Frame: The original trial design had co-primary outcomes for VTE recurrence and clinically relevant bleeding. This was changed to a composite outcome of VTE recurrence and major bleeding event.The researchers also extended the time frame from six to 12 months. The original primary outcomes at six months are not listed in the publication and can only be found in the supplementary appendix.

These results showed noninferiority of edoxaban compared to LMWH for recurrent VTE (6.5 percent versus 8.8 percent; HR 0.75 [95% CI, 0.48–1.17]), but an increase in clinically relevant bleeds (15.9 percent versus 10.7 percent; HR 1.54 [95% CI, 1.10–2.16]). There was no difference in all-cause mortality or event-free survival.

- Noninferiority: This trial was designed to see if oral edoxaban was not worse (noninferior) than LMWH. What about patient satisfaction of an oral medication compared to a daily injection? There was also no mention of cost, which may play a role in determining noninferiority.

- Conflicts of Interest: The authors reported multiple conflicts of interest, and the trial was sponsored by the maker of edoxaban. The pharmaceutical company, in collaboration with the coordinating committee, was responsible for the trial design, protocol, and oversight, as well as collection and maintenance of the data. It also performed all the statistical analysis in collaboration with the writing committee. This does not make the data wrong but should make us more skeptical.

Bottom Line

It may be reasonable to discuss oral edoxaban with patients as a potential treatment for cancer-associated VTE. However, the decision should probably be left up to the patient and their oncologist.

Case Resolution

The patient is given LMWH and has outpatient injections arranged. He is referred back to his oncologist to further discuss the issue of using a DOAC to manage his cancer-associated DVT.

Thank you to Dr. Anand Swaminathan, assistant professor of emergency medicine at the St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center in Paterson, New Jersey.

Remember to be skeptical of anything you learn, even if you heard it on the Skeptics’ Guide to Emergency Medicine.

References

- Lee AY, Levine MN, Baker RI, et al. Low-molecular-weight heparin versus a coumarin for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(2):146-153.

- Beam DM, Kahler ZP, Kline JA. Immediate discharge and home treatment of low-risk venous thromboembolism diagnosed in two U.S. emergency departments with rivaroxaban: a one-year preplanned analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(7):788-795.

- Young AM, Marshall A, Thirlwall J, et al. Comparison of an oral factor Xa inhibitor with low molecular weight heparin in patients with cancer with venous thromboembolism: results of a randomized trial (SELECT-D). J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(20):2017-2023.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

One Response to “Should You Use Direct Oral Anticoagulants for Cancer-Associated VTE?”

January 20, 2019

Gregg ChesneyThanks for this review! I had this exact debate last week (but enoxaparin vs rivaroxaban) with our ED pharmacist, the patient’s oncologist and his general surgeon for a patient with an acute DVT 2 weeks post-op from a resection of a colonic adenocarcinoma. I hadn’t seen the new article in the NEJM yet, and the 2016 ACCP VTE guidelines are still recommending LMWH. I had originally ordered enoxaparin but the oncologist decided he wanted to manage him on rivaroxaban, citing new data that DOACs are noninferior in these patients, which I hadn’t had a chance to look for yet, so thanks for filling me in!