A problematic manuscript regarding the “work-up” of strangled patients, authored by Zuberi et al. and published in 2019 by the journal Emergency Radiology, has recently come to our attention.1 This manuscript downplays the risks for traumatic dissection of the arteries of the neck caused by strangulations, which can lead to a cerebrovascular accident (CVA), or “stroke.”

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 41 – No 06 – June 2022If a consultant radiologist cites the findings of Zuberi et al., while attempting to dissuade the emergency physician from obtaining indicated computed tomography angiography (CTA) or magnetic resonance angiography of the head and neck for a strangled patient, our summary could assist the emergency physician to capably refute that radiologist’s assertions and persuade them to perform the indicated testing. Our rationale centers not only upon the science of the matter, but also upon the risk for failing to meet the requirements of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) statute regarding the detection and stabilization of an emergency condition.

A strangulation typically occurs when forces are applied circumferentially around or focally to the neck, often by use of the hands and/or forearms, or via a ligature. Patients who have suffered strangulations that do not cause hyoid fractures or immediate airway compromise typically present to the emergency department (ED) for evaluation and management. (The term “choking” should be reserved for instances in which a cough or gag reflex occurs due to defective swallowing, causing temporary and/or partial blockage of the trachea.)

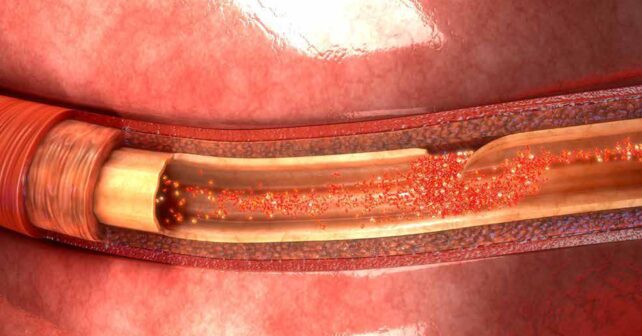

Emergency physicians are all too aware that many strangulations occur in the setting of domestic violence, and not all strangled patients show obvious initial signs of their injuries.2,3 Strangulations can acutely compromise arterial flow to or venous drainage of the brain, resulting in temporarily insufficient cerebral perfusion, which can cause unconsciousness or incontinence. Except for an acute or delayed airway emergency, the “worst-case” scenario for a patient who has been strangled and survived the attack is to have developed an intimal tear, causing an arterial dissection that can lead to a subsequent ischemic cerebrovascular accident (CVA).4 Such intimal tears are more likely when strangulation has involved digital compression of a carotid artery or vertebral transverse process. Tears and dissections may also follow “chokeholds” as used in martial arts and in some police-applied restraints, where sudden, forceful cervical twisting and/or stretching has occurred.

An “expert consensus” from the Training Institute on Strangulation Prevention (TISP) exists regarding which history and physical examination findings suggest a significant risk for an arterial dissection.5 The 11 clinically-reasonable high risk criteria cited by the TISP include a transient loss of consciousness while being strangled, visual changes such as “flashing lights” or “tunnel vision,” intraoral, facial, or conjunctival petechiae, contusions or ligature marks to the neck, tenderness to palpation near the carotid artery, incontinence of bowel or bladder, new neurologic symptoms, dyspnea, dysphonia, odynophagia, and/or subcutaneous emphysema.5

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Single Page

No Responses to “It’s OK to Order Angiography Tests for Strangulation Victims”