However, this expert consensus to predict who will not harbor a dissection was not informed by statistical modeling (as today’s clinical prediction tools are).6 The risk factors cited by the TISP are qualitative and their relative contributions to prediction of risk for CVA have not been quantified.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 41 – No 06 – June 2022Further, an emergency physician’s general obligation under the EMTALA statute is to evaluate the patient with a sufficient index of suspicion toward the detection of any emergency condition that might be present, to diagnose such conditions when they have occurred, and to render or refer elsewhere for appropriate definitive care.7 The EMTALA statute does not shield consultant radiologists from financial penalties when their clinical choices contribute toward a violation. The fact that arterial dissections after strangulation have a low likelihood does not matter. A low likelihood, in a condition with such devastating potential, does not imply that such outcomes have no likelihood.

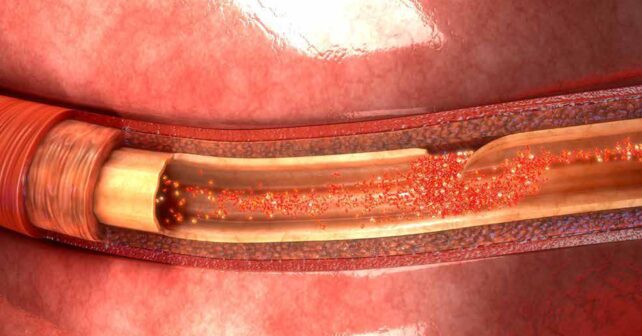

Therefore, when emergency physicians evaluate strangled patients, one of the principal questions to be addressed, once it is clear that no airway emergency exists, is whether or not they are caring for that rare patient who harbors an arterial dissection and requires timely anticoagulation treatment to prevent an ischemic CVA.

To add clarity to this dilemma, Zuberi et al., prospectively assembled a cohort of 142 patients who endured strangulation and presented for emergency care at a single site over seven years.1 The initial readings of the angiograms obtained for these patients suggested six of the 142 patients harbored a vascular injury. Several of these initial readings were changed after review. Once these retrospective reviews of the angiograms were complete, four patients were determined to have a significant vascular injury. This included three with initial “true positive” findings, three with “false positive” findings, and one with an initial “false negative” finding. Unfortunately, the authors then dismissively concluded, “Performing CTA of the neck after acute strangulation injury rarely identifies clinically significant findings, with vascular injuries proving exceedingly rare.”

First, we believe that this conclusion may lead radiologists to under-estimate the degree of need and urgency present when emergency physicians order angiographic testing of strangled patients. The authors should not have downplayed the importance of the relatively few positive tests. Second, Zuberi et al. also failed to note the radiologists’ general obligations and risk for financial penalties if they are judged to be in non-compliance with the EMTALA statute. Third, they should have noted not only the non-zero probability for a dissection, but also the discordance between the initial and final reading of the angiograms. This could have led to advocacy for a period of observation that would enable angiograms to be over-read before the patient left the emergency department.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Single Page

No Responses to “It’s OK to Order Angiography Tests for Strangulation Victims”