The emergency department serves as both the lifeline and the gateway to psychiatric care for millions of patients suffering from acute behavioral or mental health emergencies. As ED providers, in addition to assessing the risk of suicide and homicide, one of our most important responsibilities is to determine whether the patient’s behavioral emergency is the result of an organic disease process, as opposed to a psychological one; there is no standard process for this.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 36 – No 09 – September 2017On the one hand, these psychiatric patients are high-risk medical patients. They not only have a higher incidence of chronic medical conditions, but they’re at greater risk of injury, including serious head injury, than the general population. The rate of missed medical diagnoses in the emergency department ranges from 8 to 48 percent, with the highest missed diagnosis rate among first presentations. Any and all acute medical emergencies need to be identified. The admitting psychiatric team certainly shouldn’t be burdened with a missed medical emergency.

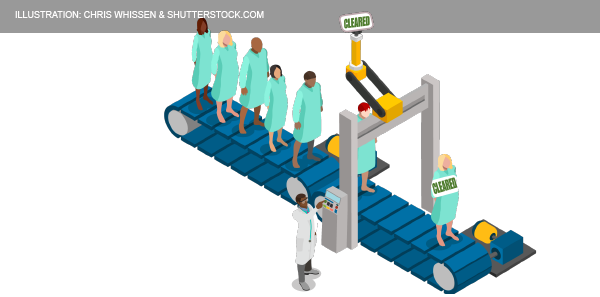

On the other hand, psychiatric patients can stress the emergency department, with the average length of stay ranging from 15 to 30 hours, depending on the whether they require medical clearance and whether they are admitted.1,2 Lack of agreement between the emergency department and the psychiatric department can lead to the adoption of arbitrary exclusionary criteria, which delay admissions even further. In one study, the total costs were $17,240 per patient requiring medical screening.3 So, having these patients who are at high risk for acute medical problems that need to be dealt with before their disposition while at the same time wanting to move them through the system efficiently poses significant challenges. An appropriate and accurate medical clearance process is imperative for decreasing length of stay in the emergency department and the cost of care as well as for identifying medical issues that may be causing or exacerbating the patients’ presentation.

General Approach to Behavioral Complaints

Overall, the approach to patients presenting with behavioral complaints should be the same as the approach to those with general medical conditions: ABCs, a thorough history (including collateral history) and physical, and selective testing.

History and physical exam remain the mainstays of evaluation; the minimum data set should include full vital signs, history including record of mental illness, medications, substances, mood and thought content, mental status exam, and further examination as indicated by the presentation. In a 1997 study by Olshaker et al of 345 patients presenting to an emergency department with psychiatric complaints, a complete history was the most sensitive, at 94 percent, for identifying a common medical condition compared to physical and lab tests.4 If you are unable to obtain a history from an altered patient, the risk for missing an important medical illness goes up significantly.

Historical Clues to Differentiate Organic Versus Psychiatric Illness

Patients who present with an altered level of awareness or a dramatic change in behavior often end up getting extensive and expensive workups that could be avoided by asking them a few simple questions: Where do you live? Who do you live with? How do you support yourself? Do you have any outstanding charges you’re facing? Have you ever been in jail? What substances do you regularly use? Where were you just before you came to the emergency department?

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Single Page

No Responses to “How to Tell Whether a Psychiatric Emergency is Due to Disease or Psychological Illness”