In the emergency department (ED), physicians face the challenge of making rapid decisions that can significantly impact patient outcomes. These decisions often require a balance between clinical acumen and an open-minded approach, particularly in cases where symptoms could point to both mental health crises and physical health issues. A recent encounter highlights the critical importance of avoiding diagnostic anchoring, especially in patients of color, those who present with mental health crises, and the intersection that lies between them.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 43 – No 10 – October 2024The patient, a 25-year-old male of color, arrived at the ED with persistent tachycardia, his heart rate consistently in the 120s. Accompanying this symptom was a significant “heavyweighted” chest discomfort that he had been experiencing for months. He had a prescription for a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) for panic disorder and anxiety. He had a significant medical history of mental health crises, and this seemed to be his typical presentation pattern. Given his history, it could have been easy to attribute his current presentation to his known mental health conditions. However, the persistence of tachycardia despite fluid resuscitation and dosing with lorazepam to help with his panic disorder raised concerns that warranted further investigation.

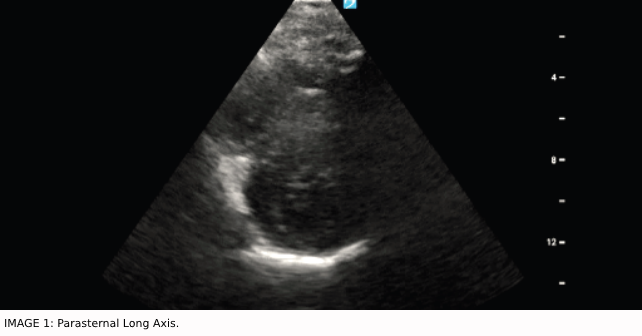

Collaborating with one of my ultrasound faculty, we conducted a bedside echocardiogram to explore potential cardiac anomalies. This examination revealed focal septal hypertrophy and raised concerns for systolic anterior motion (SAM) of the mitral valve, findings that pointed to a potential physical underpinning for the patient’s symptoms. The patient had an assortment of previous doctor’s visits attempting to identify the cause of his panic episodes. Furthermore, this patient had been having episodes of palpitations that had been worsening since he was a teen, and there was, unfortunately, never an investigation regarding these persistent episodes.

HOCM in the ED

HOCM is not an everyday diagnosis in the ER. However, this should not deter us from including it in our differential, especially among younger patients. Up to 30 percent of people in this population will not have any family history at all before HOCM is identified.1 The diminished left ventricular function in HOCM is often associated with the thickening of the interventricular septum, which is also associated with increased left ventricular wall thickness equal to 15 mm or more. Furthermore, this genetic cardiac disease is autosomal dominant, presenting 1 in 500 in our general population.2 This is particularly problematic as we know that many of our HOCM patients, despite being asymptomatic, have nearly a 25 percent chance of sudden cardiac death.3 This data further emphasizes how life-changing a diagnosis can be if caught early.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

No Responses to “The Intersections of Physical and Mental Health Disorders”