The use of thrombolytics for acute ischemic stroke may be one of the most controversial topics in emergency medicine during the last several decades. This debate recurs in multiple forums including many previous pieces in ACEP Now.1 The reason is understandable—thrombolytics in stroke is a high-risk, higher-reward treatment. If the potential for harm were absent, or if the benefit of thrombolytics was only marginal, there would be no controversy. Because both real risk and very real reward are at play, the debate persists.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 43 – No 12 – December 2024However, like any topic—including the optimal medications for rapid sequence intubation or whether Pepsi is better than Coke—these discussions largely live in a stratosphere far above our daily clinical practice. In the setting of regular patient care, the debate is over. There continues to be consistent evidence favoring treatment. Professional organization guidelines universally support the use of thrombolytics, including the American Heart Association and ACEP.2,3 Hospital policies and stroke protocols include thrombolytic administration for eligible patients as a rule. Systems of care have evolved to better support emergency physicians in overall stroke care and, specifically, decisions on giving thrombolytics. Because of the increased availability of neurology consultation, expansion of telestroke, and clear hospital protocol, emergency physicians are less alone in deciding when to give thrombolytics. Another argument is also there—emergency physicians don’t want to be sued; data consistently show that medical malpractice risk is much greater for undertreatment of stroke. When we care for eligible patients with ischemic stroke in the emergency department (ED), there is no debate: We administer thrombolytics when the opportunity presents.

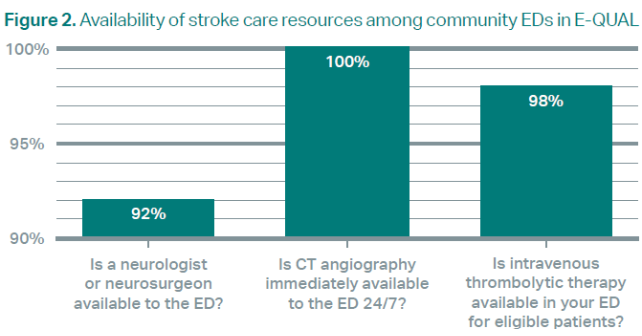

Acceptance of thrombolytics in stroke is exemplified in the results from a survey of EDs participating in ACEP’s Emergency Quality Network (E-QUAL) Stroke Collaborative. This learning network engages community EDs, regardless of setting or size, that are interested in improving stroke care. As part of the collaborative, we performed a capabilities assessment to understand the resources of participating sites. Last year’s assessment demonstrated widespread adoption of thrombolytics for stroke among emergency physicians (see Figure 1).

Diagnostic Efficiency

Moving past the debate of whether to administer thrombolytics enables us to engage in a new set of conversations related to stroke care in the ED.

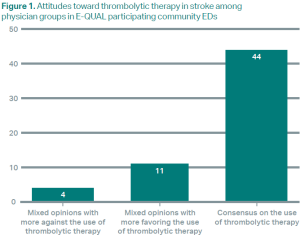

First, we are now operating in a paradigm in which the ED can provide tremendous diagnostic efficiency for acute stroke. Nearly all community EDs reported having access to CT angiography, thrombolytics, and even neurology (see Figure 2). Many (71 percent in our sample) even had access to perfusion imaging, whether through MRI or CT perfusion.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

No Responses to “Thrombolytics in Stroke: Moving Beyond Controversy to Comprehensive Care”