Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 36 – No 03 – March 2017(click for larger image)

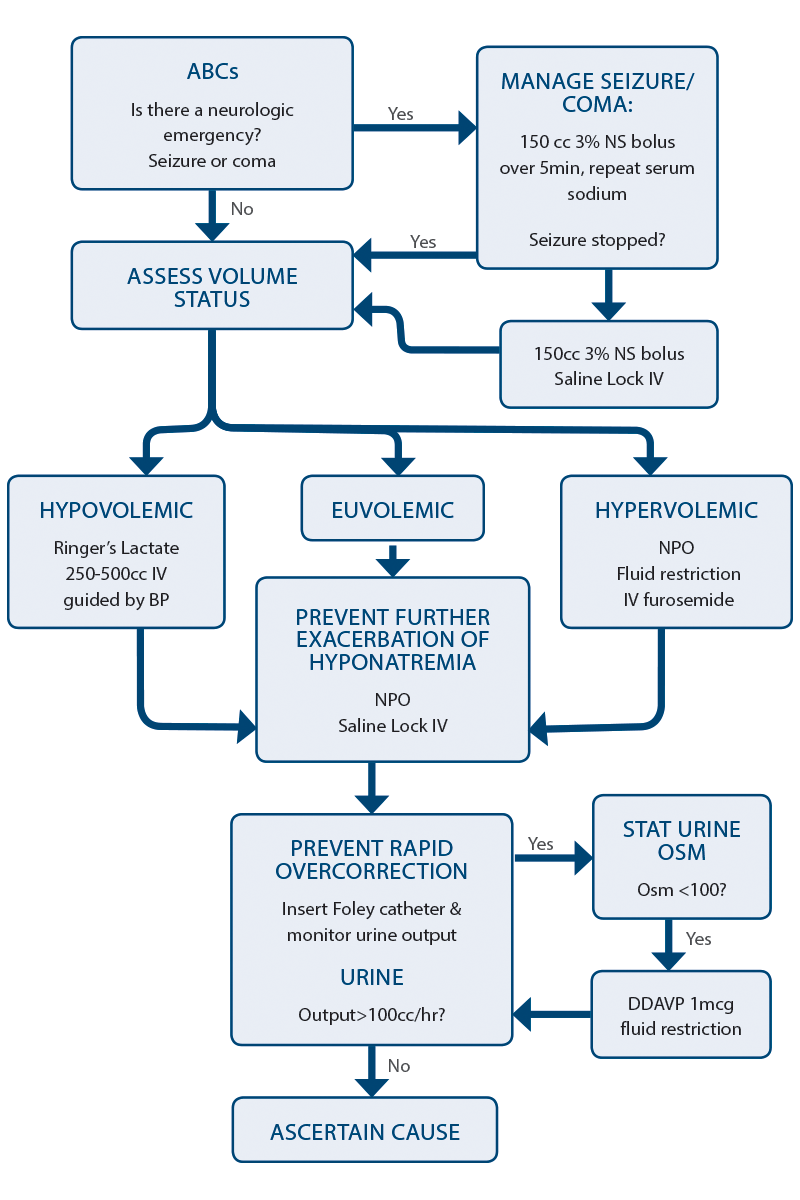

Figure 1: Algorithm for Managing Hyponatremia in the Emergency Department

Hyponatremia is the most common electrolyte abnormality seen in clinical practice. Not only is it found in about 20 percent of hospital admissions, but hyponatremia is an independent predictor of mortality. Part of the reason for this is, unfortunately, iatrogenic because misguided efforts to correct hyponatremia can be devastating for the patient and are a common reason for medical-legal action. Overcorrection can put patients at risk for osmotic demyelination syndrome (ODS), formerly known as central pontine myelinolysis.

There are two factors that influence how symptomatic a patient will be from hyponatremia: severity of hyponatremia and the acuity of onset. The lower the sodium and the faster the fall, the more symptomatic a patient will become. The rapidity of onset is important to ascertain because aggressive rapid correction of a slow-onset hyponatremia is more likely to result in complications. Symptoms are often vague and nonspecific and include headache, irritability, lethargy, confusion, agitation, and unstable gait leading to a fall. Thus, hyponatremia is often discovered incidentally on “routine” blood work.

Step-Wise Approach to Managing Hyponatremia

1. Treat neurologic emergencies related to hyponatremia. In the event of a seizure, coma, or suspected cerebral herniation as a result of hyponatremia, 3% hypertonic saline 150 mL IV over five to 10 minutes should be administered as soon as possible. If the patient does not improve clinically after the first bolus, repeat a second bolus of hypertonic saline. It is important to stop all fluids after the second bolus to avoid raising the serum sodium any further. If hypertonic saline is not readily available, administer one ampule of sodium bicarbonate over five minutes.

2. Defend the intravascular volume. In order to maintain a normal intravascular volume, the patient’s volume status must first be estimated. Although volume status is difficult to assess with any accuracy at the bedside, a clinical assessment with attention to the patient’s history, heart rate, blood pressure, jugular venous pressure, the presence of pedal and sacral edema, the presence of a postural drop, and point-of-care ultrasound is usually adequate to make a rough estimation of whether the patient is significantly hypovolemic (requiring fluid resuscitation) or significantly hypervolemic (requiring fluid restriction or diuretics).

In a patient who is hypovolemic and hyponatremic, the priority is to restore adequate circulating volume. This takes priority over any concerns that the hyponatremia might be corrected too rapidly and lead to ODS.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

No Responses to “Tips to Assess Rapid Onset of Hyponatremia to Prevent Overcorrection and Diagnose Underlying Cause”