Alternatively, fractures can occur via normal force on abnormal bone. For example, an 85-year-old man with osteoporosis falls from a standing height and suffers a comminuted fracture of his distal radius. Elderly patients commonly fracture their hip without falling—it can be secondary to a relatively minor rotational force applied to an osteoporotic long bone.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 37 – No 09 – September 2018So for those with weaker bone (i.e., the elderly and young) we should have a heightened awareness for fracture—and therefore require greater skepticism for a normal X-ray.

Better detection of occult fractures starts with appreciating that, for some reason, many clinicians have a different (perhaps flawed) diagnostic approach to musculoskeletal patients. When a normal radiograph is available prior to exam, our index of suspicion declines, but it shouldn’t be zero. Don’t be biased by a normal radiograph. Shortchanging a patient’s history and physical exam opens the door to missing subtle presentations.

To diagnose a patient with a fracture, do your best to determine:

- The mechanism of injury, including both the magnitude and direction of force—these factors predict injury patterns.

- The events after the injury. Delayed pain is less likely to be a fracture.

- Age, previous injuries, past medical history, and medications. Younger patients have softer/weaker bone; older patients have osteoporosis; orthopedic implants give rise to subtle periprosthetic fractures; neuropathy diminishes pain; long-term steroids can cause osteoporosis, etc.

- Signs of fracture, such as swelling, focal tenderness, and decreased range of motion. We must use the physical exam to confirm what we suspect by history.

Once you have determined a differential diagnosis for a patient and your pretest probability for a fracture, then (and only then) should you consider an X-ray. In fact, if the likelihood of an abnormal X-ray is low, then consider not ordering the test. And if your pretest probability is high, don’t dismiss a diagnosis of fracture just because the X-ray is normal.

As diagnosticians, we routinely apply Bayes’ theorem. We determine a pretest probability based on the history and physical exam. Then we order and interpret the test. With the result(s), we now determine our posttest probability.

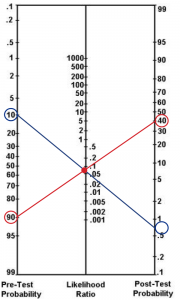

Likelihood ratios (LRs) help us understand the value of a diagnostic test.5 An LR of 1 adds nothing to our diagnostic impression. But a high or low LR can make a diagnosis more or less probable, respectively.

The literature is not clear on a target LR for emergency department patients with a musculoskeletal injury and a negative X-ray, but a reasonable estimate is 0.05–0.1. For such patients, there is about a 90 to 95 percent chance they do not have a fracture versus a 5 to 10 percent chance they do have a fracture. So for the following examples, let’s split the difference and use an LR of 7.5 percent (ie, 0.075).

Example Patients

(click for larger image) Figure 1: A Fagan nomogram can be used to chart the chance that a patient with a negative X-ray has a fracture. Using a likelihood ratio of 0.075 (center line), the 10 percent pretest probability (left line) of Patient A (blue line) indicates a less than 1 percent post-test probability (right line). The 90 percent pretest probability (left line) of Patient B (red line) indicates a 40 percent post-test probability (right line).

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Single Page

No Responses to “Tips for Diagnosing Occult Fractures in the Emergency Department”