Acute Mountain Sickness and High-Altitude Cerebral Edema

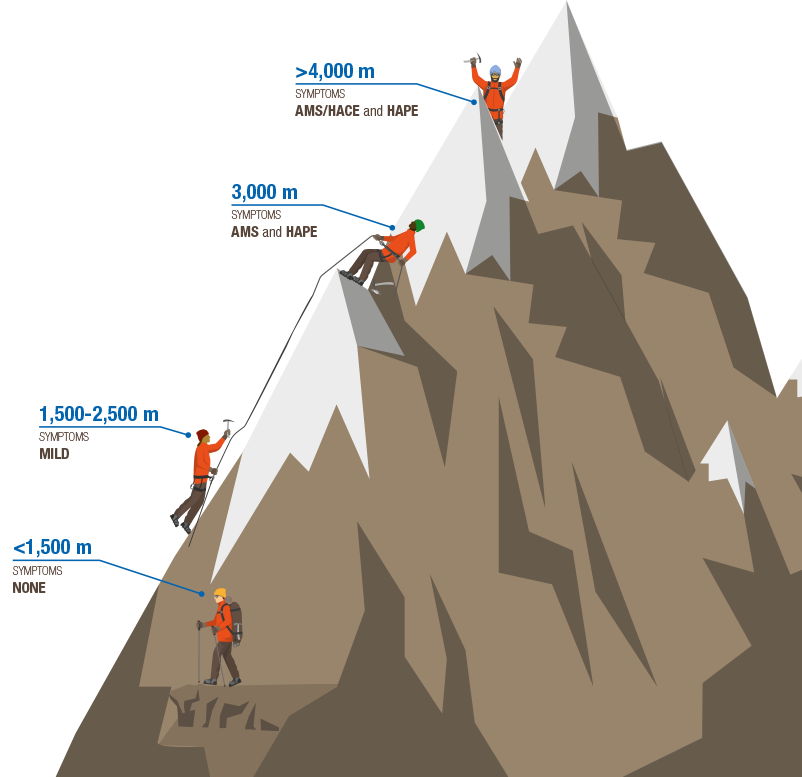

The pathophysiologies of the neurological forms of HAI—AMS and HACE—are similar in that there is an increase in the permeability of the blood-brain barrier causing reversible vasogenic edema. The mechanism of this increased permeability is unclear. There is a possible increase in cerebral blood flow, loss of intracranial pressure autoregulation, and resultant alterations in endothelial permeability via increased nitric oxide levels and increased vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which promotes angiogenesis. AMS and HACE are along a spectrum of disease, with AMS occurring around 1,500 meters with typical transition to HACE at more than 4,000 meters. The diagnosis for AMS is clinical, with symptoms that resemble a hangover, such as headache, anorexia, nausea, and vomiting.1 Onset of AMS generally occurs within six to 12 hours of reaching altitude and resolves within one day, but it can recur as ascent continues. The Lake Louise AMS score is the gold standard to self-monitor for AMS during ascent or for a clinician evaluating a patient.5,6 HACE is a clinical diagnosis, with onset at 12 hours to three days from ascent. The patient will present with ataxia, encephalopathy, and a progressive decline of mental function and level of consciousness. Patients may first only appear to be withdrawn; clinical suspicion should be high. Physical examination will reveal a patient with impaired finger-to-nose or heel-to-shin testing. All labs and imaging are fairly nonspecific, but they may show leukocytosis and possibly cerebral edema.1,7

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 38 – No 05 – May 2019

TYpical Elevations for High-Altitude Illness

ILLUSTRATION: Chris Whissen & shutterstock.com

Treatment of AMS consists of symptomatic management with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSIADs), antiemetics, and a pause in ascent for 48 hours for acclimatization to occur. Treatment for HACE is immediate descent. If that is not possible, the patient should be treated in a hyperbaric chamber, along with 2–4 L nasal cannula and dexamethasone for alleviation of symptoms related to cerebral edema. In the event the patient becomes unresponsive, consider protecting the airway.2,4

Prescription medications can be used for treatment but are better as preventative measures. Acetazolamide, a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, initiates metabolic acidosis, theoretically stimulating respiratory drive and hastening acclimatization, but its side effects can be mildly irritating, with peripheral paresthesia, polyuria, and a metallic aftertaste. Dexamethasone can be used to alleviate symptoms, but it does not accelerate acclimatization. The risk with dexamethasone is that it masks symptoms and therefore may increase the risk of AMS progressing to HACE as ascent continues.2,4

For AMS and HACE, the gold standard for prevention is gradual ascent, acetazolamide, and +/- dexamethasone. Dexamethasone is typically used in prevention of AMS/HACE for patients who require rapid ascent but does not hasten acclimatization. There are multiple drugs that, when compared to placebo, do show improvement for prevention, such as acetazolamide and dexamethasone. As a selective 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor agonist and a cerebral vasoconstrictor, sumatriptan shows promising results for AMS prevention; however, only one study has been published, which showed decreased prevalence of AMS in sumatriptan versus placebo when used for prophylaxis.8 Further studies would need to be completed prior to utilizing sumatriptan as a preventative medication. Antioxidants, magnesium, ginkgo biloba, and cocoa leave use have very limited data and scattered anecdotal reports, with no significant difference shown when compared to acetazolamide and dexamethasone.2,4,9

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Single Page

One Response to “Tips for Spotting and Treating High-Altitude Illness”

June 9, 2019

Timothy Peterson MDI love your succinct synopsis, as a physician who has practiced at 9,300 feet for thirty-one years.

Comments:

1.) We prefer O2, acetaminophen and ondansetron to NSAIDS in the nausea scenario. NSAIDS recommendations persist based on poorly designed earlier NSAID prevention studies which have been discounted. Why give NSAIDS to folks with nausea and vomiting?

2.) For those of us in the real world, the Lake Louise score is academic and impractical from the perspective of having treated over five thousand AMS patients. We take a history, do an exam, look for clinical improvement in patient w/o concurrent medical illness after 20 min 02 trial, then make a treatment decision. A score sounds good but does not help.