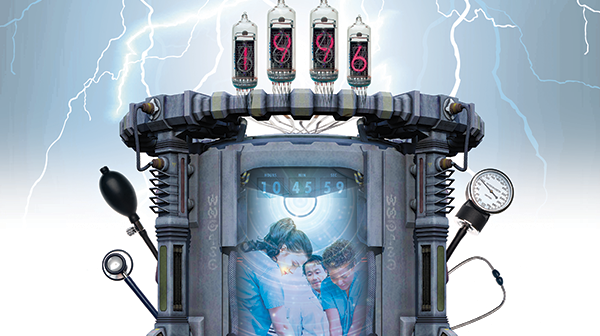

What students raised in the millennial generation will bring to the health care workforce, and how medical school admissions, technical standards, and applicants have changed

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 33 – No 02 – February 2014Recently, I was sitting in our admissions committee meeting, getting ready to discuss the applicants we had interviewed. One of the other members chuckled and said, “Wouldn’t it be funny if we all brought our own medical school applications one day to review?” As we all laughed and looked around at one another (a bit uneasily, I might add), the only thing that kept going through my head was, “Awww, hell no.” (If you could, try to hear that with a little Alabama Southern drawl—it makes it sound much sweeter.)

I graduated from medical school in 1996, and things have drastically changed during the past 25 years. There are different standards and different expectations.

The Other Medical Reform

Abraham Flexner was an American educator who studied at Johns Hopkins University. He was invited by the Carnegie Foundation to review medical schools in the United States and Canada and to make recommendations for improvement. Interestingly, he evaluated these institutions from the viewpoint of an educator, not a medical practitioner. Based on his evaluations, the schools were placed in one of three categories:

- Those that compared favorably with Johns Hopkins (the gold standard)

- Those considered substandard but salvageable by providing financial assistance

- Those of such poor quality that they should be closed (sadly, the majority)1

And many schools were closed. Of the 133 MD-granting medical schools open and reviewed in 1910, only 85 remained in 1920.2 Some of the findings from Flexner’s study changed the landscape of medical education with drastic improvements. It was Flexner’s report that first suggested that clinical exposure was as vital to medical education as “a laboratory of chemistry or pathology,” encouraging hospitals both private and public to open their wards to teaching. This was with the caveat that the universities have sufficient funds to employ teachers who were dedicated to clinical science, highlighting the underlying deficiencies of medical schools to keep up with the increasing costs of quality medical education.3 This report was the beginning of the end of medical education as a for-profit enterprise.

Getting In

Fast forward 100 years. Gone are the days when two years of college (or less) could get you into medical school. Today, there are 129 fully accredited four-year U.S. medical schools, and in 2012 there were 45,266 applicants and 19,517 matriculants (46% of whom were female). Although admission requirements vary by institution, there are some universal standards. Most schools will have a minimum MCAT score and a certain number of undergraduate hours, including science, math, and English. GPAs are more flexible than MCAT scores, but special note is typically taken of the science GPA. Of note, the MCAT must be taken within three years of application, and there is a new MCAT that will launch in 2015 (after undergoing its fifth revision). Letters of recommendation are required, the most telling usually coming from the pre-health advisor at the undergraduate institution. Each institution has its own technical standards that need to be met, with reasonable accommodations, and include both physical and emotional components. And then there’s the other stuff.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Single Page

No Responses to “Today’s Medical Students and the Medical School Landscape”