The Case

You get a call that a 50-year-old woman collapsed while running a marathon. Bystanders started CPR immediately. Nearby paramedics found her to be in ventricular fibrillation (VF). She was shocked three times and given 3 amps of epinephrine. She is still in VF when she arrives at your emergency department.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 36 – No 07 – July 2017Advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) was originally designed to give us a common language and help us avoid paralysis in a crisis situation. However, with each year that passes, it seems like ACLS has become more and more simplified to appeal to a broader scope of rescuers, including those who rarely run codes. Yet cardiac arrest physiology just isn’t that simple. Managing these patients requires a lot more finesse. Practitioners working in settings where they manage codes regularly (eg, the emergency department) should be expected to have a more sophisticated approach when standard ACLS algorithms aren’t effective. In this month’s column, I’ll suggest four strategies to improve the chances of return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) in shock-resistant VF and, perhaps, survival to hospital discharge. Shock-resistant VF, or electrical storm, is defined as three or more sustained episodes of VF in a 24-hour period.

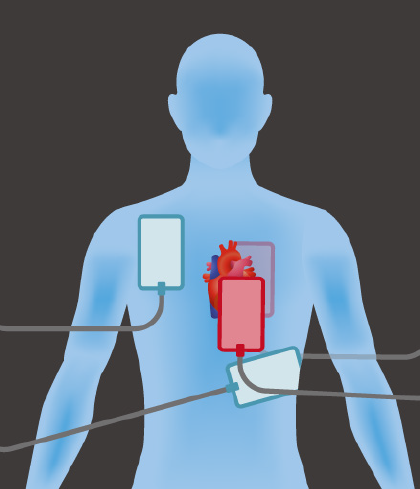

To perform dual-shock defibrillation, place one set of defibrillator pads in the traditional positions on the chest (blue pads) and attach a second set of pads from a second defibrillator in the anterior-posterior “sandwich” position (red pads).

ILLUSTRATION: Chris Whissen & Shutterstock.com

1. Prepare Your Team

Team-based preparation prior to patient arrival is essential to optimizing cardiac arrest care and takes fewer than five minutes. It can be broken down into three points to be discussed in a team huddle:

- What do we know? What do we expect to see? What are the possibilities? Run through the most likely immediate life-threatening issues.

- What do we do? What actions will you take, and what contingency plans will you have in place if those actions fail? Teams respond more efficiently and decidedly if they have anticipated failure rather than having failure of a plan surprise them.

- Role assignment: Assign logistical tasks to team members, including definitive airway management, chest compressions, medication administration, and defibrillation.

In this case, consider premixing amiodarone 300 mg and esmolol 500 mcg/kg and setting up for dual-shock therapy.

2. Consider Stopping Epinephrine

Epinephrine is associated with increased myocardial oxygen consumption and ventricular dysrhythmias and has never been shown to improve survival to hospital discharge in cardiac arrest.1 Epinephrine, in the doses used in cardiac arrest, causes cerebral vasoconstriction that may impair tissue oxygenation and brain perfusion and compromise neurological recovery.2 There is an argument to be made that epinephrine should be decreased or eliminated in all patients with shock-refractory VF because of its catecholamine effects. It makes little physiologic sense to add catecholamine fuel, like epinephrine, to the catecholamine firestorm of refractory VF. In fact, we want to achieve the opposite: Block the catecholamine surge so that the VF breaks.

3. Block Sympathetic Tone

Shock-resistant VF increases sympathetic tone, which leads to a vicious cycle of fibrillation and increased sympathetic tone.3 Esmolol decreases sympathetic tone and counteracts the endogenous and exogenous catecholamine surge theorized to occur during refractory VF arrest. Esmolol is the only drug in the management of cardiac arrest that has shown an increased rate of survival to hospital discharge with favorable neurologic outcomes. Albeit in a small study, patients who received esmolol after three defibrillations and 3 mg of epinephrine had a 50 percent survival to hospital discharge with a favorable neurologic outcome compared to 11 percent of patients who did not receive esmolol.4 Larger randomized controlled trials are needed. However, in the meantime, there is little downside to giving esmolol in this setting.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

No Responses to “Treatment Strategies for Shock-Resistant Ventricular Fibrillation”