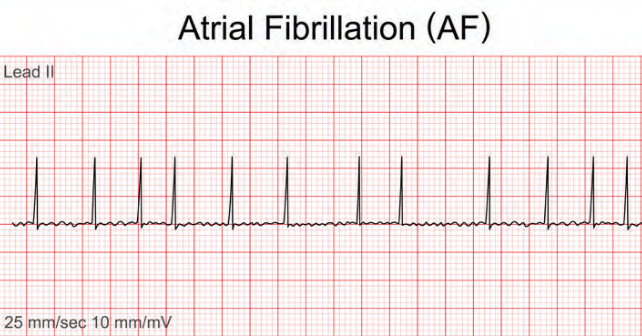

The American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology released a comprehensive guideline on the management of atrial fibrillation (AF).1 Most of the AHA/ACC recommendations are either irrelevant to the general emergency physician or common sense. For example, if a patient has hemodynamic instability attributable to AF, perform immediate electrical cardioversion. That recommendation is not controversial; however, some interesting recommendations within these guidelines may reshape clinician practice, particularly regarding rate control strategies.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 43 – No 08 – August 2024Rate Versus Rhythm in the ED

The 2023 AHA/ACC guideline doesn’t give explicit recommendations or preference regarding initial rate or rhythm control strategy for new-onset AF patients who are hemodynamically stable. The guideline states that electrical cardioversion can be performed (Class 1, Level B evidence from randomized trials) and suggests that, if you go this route, you should start with at least 200 joules to increase success (Class 2a, Level B evidence from randomized trials).

The Beta Blocker Versus Calcium Channel Blocker Debate

The ideal control agent for patients with AF with rapid ventricular response (AFRVR) is widely debated in emergency medicine. Often, the best means of rate control is control of the underlying disease process (e.g., antibiotics and fluids or diuresis); however, most emergency clinicians probably have a “favorite” means of rate control for patients with AFRVR. Intravenous (IV) metoprolol and diltiazem are the most commonly administered rate control agents for AFRVR. The current iteration of the guideline does not signal a preference between beta blockers and nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (CCBs) for most patients. In fact, few studies compare the two classes.2

Heart failure, however, is a different story. The 2023 AHA/ACC guideline has warned clinicians to essentially toss their IV nondihydropyridine CCBs in the trash for any patient with systolic dysfunction. The panel gave a rare Class 3: harm recommendation for the use of IV nondihydropyridine CCBs in patients with AFRVR and known moderate or severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction with or without decompensated heart failure (HF). This recommendation is a departure from the 2014 guideline iteration that only recommended against CCBs in patients with decompensated heart failure.3 The guideline cites low quality evidence from small studies and fear of negative ionotropic effects. Unfortunately, few studies have directly compared acute management strategies for patients with AFRVR and acute decompensated heart failure, and those that have done so have woefully inadequate sample sizes to detect somewhat uncommon but critical harms.4 The 2023 recommendation is based on consensus and two retrospective studies demonstrating some negative outcomes with exposure to diltiazem (acute kidney injury, worsening HF symptoms); however, diltiazem was not associated with mortality and hypotension. The guideline recommends amiodarone for rate control in patients with AFRVR and decompensated heart failure. Although the recommendation against CCBs for acute rate control in patients with any systolic dysfunction is largely consensus based, a paucity of data suggests that beta blockers are any more effective in this subgroup. So, while clinicians can continue to use judgment and the best medications for a given patient, the guideline will likely encourage the use of alternatives in patients with AFRVR and systolic dysfunction.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

No Responses to “Updated Guidelines on Atrial Fibrillation Management”