A quick and safe way to drain this fluid without tying up resources at the bedside.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 33 – No 07 – July 2014

A 55-year-old male with severe ascites secondary to chronic cirrhotic liver disease presents to the emergency department for shortness of breath secondary to fluid accumulation and abdominal distention. He routinely visits the ED for therapeutic paracentesis, likely due to poor follow-up as a result of being uninsured. As usual, the department is very busy, and you have many critical patients who require your attention. Is there a quick and safe way to drain this fluid without tying up resources at the bedside?

You can use wall suction and several suction canisters to create a closed continuous drainage system for removing large amounts of ascitic fluid during a paracentesis.

Often, chronic liver failure patients will present to the ED for symptomatic drainage of their ascites. Many of these patients need to have several liters drained, and this can become time-consuming in a busy emergency department. This technique allows for a quick, clean, and easy way to continuously remove this ascitic fluid.

Patient Selection

This technique may be applicable for stable patients with a large amount of ascites, usually chronic liver failure patients, who regularly have a significant amount of ascitic fluid removed via paracentesis.

This may not be appropriate for patients with a small amount of ascites or unstable patients.

Cautions and Complications

Complications of paracentesis are infrequently encountered and have been reported as low as 1.6 percent in a 2009 study.1 Most of the complications encountered, such as bleeding from the puncture site or a persistent leak of fluid from the puncture site, are considered minor. Major complications are rarely encountered, and according to newer studies on paracentesis safety, coagulopathy does not seem to increase the risk of complications from a paracentesis.2 It is imperative that all patients undergoing a paracentesis are placed on a cardiac monitor and IV access is established prior to starting the procedure. Fluid shifts from ascitic fluid removal render the patients at risk for post procedure hypotension, electrolyte abnormalities (most notably hyponatremia), and third spacing leading to the most feared complication, pulmonary edema.3 Cirrhotic liver disease is linked to hepatopulmonary syndrome and cirrhotic cardiomyopathy, placing patients at risk of pulmonary edema as a result of fluid shifts if a large volume of fluid is removed during paracentesis.4 Recommended limits for total fluid removal vary depending on the source, but the consensus among guidelines is 5–6 liters without the need for volume expanders to lessen chances of major complications.

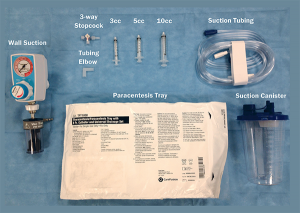

Equipment Needed

- Wall suction unit

- 3-way stopcock

- Tubing elbow

- 3, 5, or 10 ml syringe

- Suction tubing

- Paracentesis tray

- Several suction canisters

Technique

1. Prepare the patient for a standard paracentesis, and place the patient on a monitor.

2. Ensure that wall suction is available, and attach standard tubing to the wall, with the opposite end connected to the first suction canister.

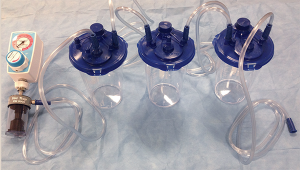

3. Another piece of tubing is then used to attach the first canister to a second canister.

4. It is important to note that most canisters have one port with a self-sealing filter (see

Figure 2). Using this port will close the system and prevent continuous flow, so it is necessary to avoid this port, except for first canister connected to the wall.

5. Once all of the tubing is connected, ensure that all other ports are capped and sealed.

6. This process for adding canisters can be repeated several times, depending on the amount of fluid to be drained. This will effectively create a suction “train,” as shown in Figure 3.

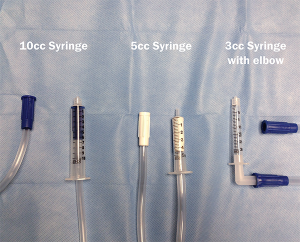

7. After you have the desired number of canisters in your “train,” take the final end of suction tubing and place it tightly into a syringe (you must first remove the plunger). Based on the size of suction tubing used and syringes at your hospital, this setup may vary, as shown in Figure 4.

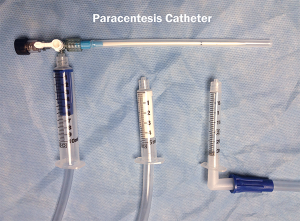

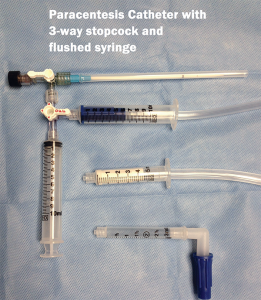

8. After successful insertion of the catheter into the peritoneal cavity, the suction syringe can be attached directly to the paracentesis catheter or first to a 3-way stopcock, as explained below in Step 10 (see Figure 5).

9. Turn the paracentesis catheter valve to the open position, and turn on the wall suction. The fluid will begin to drain into the first canister of the “train.” After filling the first canister to capacity, the fluid will continue to drain into the adjacent canister(s) without any intervention.

10. If you find that the flow stops, presumably from siphoning a loop of bowel to the catheter tip, you can integrate a 3-way stopcock with a syringe into the system (Figure 6A). This will allow you to flush the catheter with sterile saline or, preferably, the patient’s own ascitic fluid in order to push any bowel wall away from the catheter tip. If the flow stops, turn the 3-way stopcock to the off position to the suction syringe. Place the valve to the open position to a 10 ml or 50 ml syringe filled with the patient’s ascitic fluid; then flush 5–10 ml at a time through the catheter in an attempt to restore flow to the suction tip (Figure 6B). Ultrasound may also be used to determine the location of the catheter tip while flushing the fluid. Return the valve to the open position to the suction syringe, and resume the removal of ascitic fluid once flow is restored.

11. Figure 7 shows your final setup.

Dr. Jeong is an emergency medicine resident at St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center in Paterson, New Jersey.

Dr. Jeong is an emergency medicine resident at St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center in Paterson, New Jersey.

Dr. McNamee is chief resident of the emergency medicine residency at St. Joseph’s.

Dr. McNamee is chief resident of the emergency medicine residency at St. Joseph’s.

Dr. Rosenberg is chair of the department of emergency medicine, chief of geriatrics emergency medicine, and chief of palliative medicine at St. Joseph’s.

Dr. Rosenberg is chair of the department of emergency medicine, chief of geriatrics emergency medicine, and chief of palliative medicine at St. Joseph’s.

References

- De Gottardi A, Thevenot T, Spahr L, et al. Risk of complications after abdominal paracentesis in cirrhotic patients: a prospective study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:906-9.

- Wiese SS, Mortensen C, Bendtsen F. Few complications after paracentesis in patients with cirrhosis and refractory ascites. Dan Med Bull. 2011;58:A4212.

- Nelson WP 3rd, Rosenbaum JD, et al. Hyponatremia in cirrhosis following paracentesis. J Clin Invest. 1951;30:738-44.

- Sharma A. Pulmonary oedema after therapeutic ascitic paracentesis: a case report and literature review of the cardiac complications of cirrhosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:241-5.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

3 Responses to “How To Use Continuous Wall Suction for Paracentesis”

October 22, 2015

tylerTried this using the red cardinal suction canisters, which have liners. Could not get it to work. The liner gets sorta sucked up in the distal (patient) canister, and fluid kinda flows through it into the proximal (wall) canister, which fills up and cuts off suction at the valve. Is this brand dependent?

October 23, 2015

Jordan JeongHey Tyler, I think I’m following what you are describing but I do not believe it is brand dependent as we use the blue cardinal suction canisters. However we don’t have/use soft liners. This may be causing your issue. Although as long as the tubes are hooked up to the correct ports it should work. I’d like to help you get this working though. I use it all the time and it makes life much easier for me at least.

March 10, 2019

Angel FarroHello, I am a emergency medicine physician from Perú, and my question is about the proped pressure of the suction that you recommend, and the time when a volume of 5 liters can be extracted. Thank you.