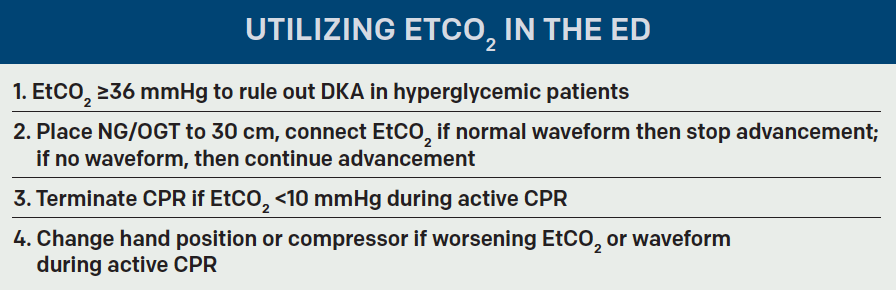

In the last “Tricks of the Trade” column (November 2016), we reviewed how to use end-tidal capnography to detect diabetic ketoacidosis and monitor chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations. Now we’ll explore using end-tidal capnography to check orogastric/nasogastric tube placement and guide cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 35 – No 12 – December 2016Using End-Tidal to Check Orogastric/Nasogastric Tube Placement

Press Ganey scores likely skyrocketed once we stopped shoving nasogastric tubes (NGT) into every patient with the slightest evidence of an upper gastrointestinal bleed, but we are still placing orogastric (OGT) or NGT in our intubated patients in the emergency department. While insertion of these tubes is a relatively straightforward procedure, it can result in fatal consequences if there is inadvertent airway placement of the tube. This dire misplacement is even possible in intubated patients with an inflated endotracheal cuff.1,2 Typically, we check for aspiration of stomach contents and auscultate to confirm placement, but these can be unreliable indicators, especially in a busy emergency department.3 The gold standard for tube placement is visualization of the tube passing below the diaphragm on chest X-ray, which you could be waiting up to 87 minutes to receive.4,5

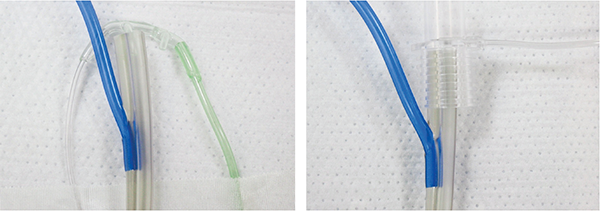

In theory, end-tidal capnograms are used to determine whether patients are hypoventilating, leading us to believe that using end-tidal to check for unintentional pulmonary placement of NGT/OGT should be effective. With the increasing availability of end-tidal capnometry in the emergency department, it is convenient enough to temporarily attach one to the NGT/OGT (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Placement of a Side-Stream Capnometer (left) and Mainstream Capnometer (right)

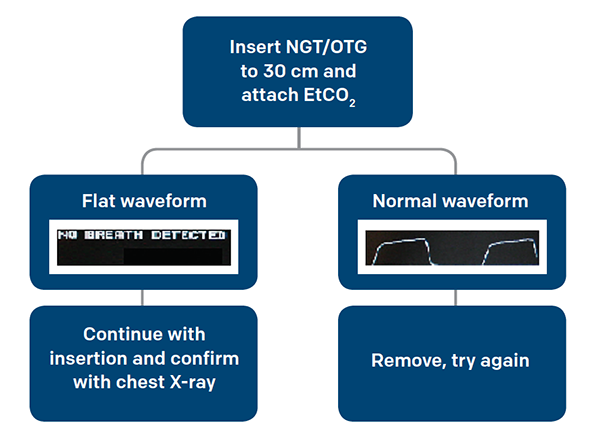

Meyer et al demonstrated that in 100 mechanically ventilated patients, a colorimetric capnometer was able to exclude tracheal placement 100 percent of the time.4 In this study, an NGT was initially inserted to a depth of 30 cm and insufflated and exsufflated with 50 cc of air, then the end of the tube was capped with the colorimetric capnometer. If the color remained purple, indicating an end-tidal CO2 (EtCO2) 15 mmHg, the tube was removed. In a meta-analysis of nine clinical trials of mechanically ventilated patients, the use of either qualitative or quantitative capnometry for tracheal placement of the NGT had sensitivities ranging from 88 to 100 percent and positive likelihood ratios of 15.2–283.5.6 Before your patient leaves the emergency department, a chest X-ray is needed to confirm placement of your NGT/OGT, but end-tidal capnography can help to avoid accidental airway insertion, multiple attempts at placement, and multiple chest X-rays. (See Figure 2 for an algorithm for placing NGT/OGT.)

Figure 2. Suggested Algorithm for Placing NGT/OGT

End-Tidal to Guide Your Next CPR

A cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is inherently a scene of chaos with many unknowns, but arguably one of most informative pieces of information, aside from presence of a pulse, is the end-tidal capnogram. End-tidal capnometry made its debut in the advanced cardiovascular life support (ACLS) guidelines in 2010, but its use in cardiac arrest can be found as far back as the 1970s.7,8 It can be used for prognostication, quality of chest compressions, correct placement of the endotracheal tube, and perhaps even the cause of the arrest.

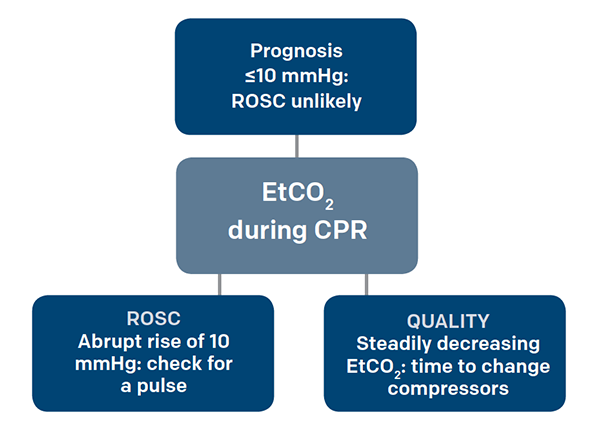

Figure 3. Using EtCO2 During CPR

When people go into cardiac arrest, they quickly become acidemic and accumulate CO2 in the blood. As CPR and ventilation begin, the CO2 is offloaded in the alveoli, expired, and subsequently sensed by the end-tidal capnometer. End-tidal CO2 has been shown to correlate with cardiac output even in low-flow states such as CPR, making it an indicator of CPR quality.9 With every increase of 10 mm in the depth of chest compressions, there is a 1.4 mmHg increase in the end-tidal value, allowing you to monitor whether the compressor is becoming fatigued and in need of relief.10 That being said, ongoing CPR should produce at least a minimal end-tidal capnogram waveform; if you see a flat capnogram, check your advanced airway for correct positioning.

The survival rates of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest are dismal, with estimations of less than 6 percent.11 End-tidal can help provide some prognostication during an active resuscitation. Having an end-tidal value less than 14.3 mmHg after undergoing 20 minutes of ACLS was predictive of not achieving return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), with a sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of 100 percent.12 In a separate study where the end-tidal value at three minutes post endotracheal intubation was measured, a value 10 mmHg was also associated with a low chance of ROSC.13 In a review of 23 observational studies related to the relationship between EtCO2 and cardiac outcomes, it was emphasized that EtCO2 cannot be used as a single prognostic factor and other characteristics of the arrest must be considered; however, the correlation between low EtCO2 and low probability of achieving ROSC was again recognized. Larger organizations, such as the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation and the American Heart Association (AHA), have agreed that low EtCO2 suggests a low probability of ROSC, with the AHA specifically mentioning values below 10 mmHg.7,14 In a more positive light, an abrupt increase of >10 mmHg in EtCO2 was associated with ROSC and shown to be a highly specific (97 percent) but not sensitive (33 percent) marker.15 During CPR, when you are typically left with very little information, end-tidal capnometry provides you with quick, reliable information that can actively guide your next resuscitation.

Conclusion

End-tidal capnometry wasn’t meant to be kept in the stable and only used for the occasional procedural sedation. Try taking it out for a ride on your next shift, whether it’s for screening the next hyperglycemic patient for diabetic ketoacidosis, monitoring for disposition of a wheezing asthmatic, resuscitating or terminating an active cardiac arrest, or confirming placement of an NGT. Remember to use caution in patients with underlying lung disease such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Throughout each shift, emergency physicians make critical decisions by pooling myriad data points from the history, physical exam, labs, imaging studies, and many other variables that we may subconsciously consider. End-tidal capnometry provides us with another data point that can aid in these crucial choices and requires few resources, money, or time.

Dr. D’Amore is an emergency medicine resident at St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center in Paterson, New Jersey.

Dr. D’Amore is an emergency medicine resident at St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center in Paterson, New Jersey.

Dr. McNamee is an attending physician at Emergency Medicine Professionals in Ormond Beach, Florida.

Dr. McNamee is an attending physician at Emergency Medicine Professionals in Ormond Beach, Florida.

Dr. McGovern is an emergency medicine resident at St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center in Paterson, New Jersey.

Dr. McGovern is an emergency medicine resident at St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center in Paterson, New Jersey.

References

- Weinberg L, Skewes D. Pneumothorax from intrapleural placement of a nasogastric tube. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2006;34(2):432-436.

- Woodall BH, Winfield DF, Bisset GS 3rd. Inadvertent tracheobronchial placement of feeding tubes. Radiology. 1987;165:727-729.

- Stroud M, Duncan H, Nightingale J, et al. British Society of B. Guidelines for enteral feeding in adult hospital patients. Gut. 2003;52(supp 7):vii1-vii12.

- Meyer P, Henry M, Maury E, et al. Colorimetric capnography to ensure correct nasogastric tube position. J Crit Care. 2009;24:231-235.

- Jolliet P, Pichard C, Biolo G, et al. Enteral nutrition in intensive care patients: a practical approach. Working Group on Nutrition and Metabolism, ESICM. European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1998;24:848-859.

- Chau JP, Lo SH, Thompson DR, et al. Use of end-tidal carbon dioxide detection to determine correct placement of nasogastric tube: a meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48:513-521.

- Neumar RW, Otto CW, Link MS, et al. Part 8: adult advanced cardiovascular life support: 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2010;122(18 suppl 3):S729-767.

- Kalenda Z. The capnogram as a guide to the efficacy of cardiac massage. Resuscitation. 1978;6(4):259-263.

- Idris AH, Staples ED, O’Brien DJ, et al. End-tidal carbon dioxide during extremely low cardiac output. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23:568-572.

- Sheak KR, Wiebe DJ, Leary M, et al. Quantitative relationship between end-tidal carbon dioxide and CPR quality during both in-hospital and out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2015;89:149-154.

- Institute of Medicine. Strategies to improve cardiac arrest survival: a time to act. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2015.

- Kolar M, Krizmaric M, Klemen P, et al. Partial pressure of end-tidal carbon dioxide successful predicts cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the field: a prospective observational study. Crit Care. 2008;12(5):R115.

- Poon KM, Lui CT, Tsui KL. Prognostication of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients by 3-min end-tidal capnometry level in the emergency department. Resuscitation. 2016;102:80-84.

- Deakin CD, Morrison LJ, Morley PT, et al. Part 8: advanced life support: 2010 international consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations. Resuscitation. 2010;81(Suppl 1):e93-e174.

- TLui CT, Poon KM, Tsui KL. Abrupt rise of end tidal carbon dioxide level was a specific but non-sensitive maker of return of spontaneous circulation in patient with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2016;104:53-58.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Use End-Tidal Capnography for Placing Orogastric, Nasogastric Tubes, and CPR”