Tranexamic acid (TXA) seems to have many uses. But where do we stand on the evidence?

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 38 – No 12 – December 2019The last time we visited the breaking literature regarding TXA, it was to examine the World Maternal Antifibrinolytic (WOMAN) trial.1 That trial generated newspaper headlines, such as “Inexpensive Drug Prevents Deaths in New Mothers, Study Finds” in The New York Times.2 On cursory glance, however, the WOMAN trial was actually a negative trial with regard to the primary outcome.

TXA recently made the news again as the results of the Clinical Randomization of an Antifibrinolytic in Significant Head Injury (CRASH-3) trial were revealed.3 With headlines in The Guardian stating “Drug Could Prevent Thousands of Head Injury Deaths,” surely this couldn’t be yet another negative trial, could it?4

Amazingly enough, it is.

Background

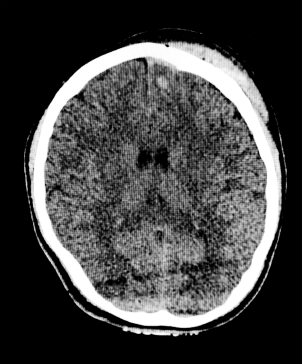

Shutterstock/AndaPhoto.

CT scan of subdural hematoma and intracranial hemorrhage.

Tranexamic acid is a staple of traumatology. It is on the World Health Organization’s list of essential medicines. It has been around since the 1960s, initially designed as treatment for menorrhagia. It can be bought over the counter for this purpose in Europe.

A synthetic analogue of the amino acid lysine, TXA binds to plasminogen, preventing conversion to plasmin and subsequent fibrin degradation. TXA became prominently used in many clinical practices following the CRASH-2 trial, which tested its efficacy in trauma patients with either significant hemorrhage or risk for significant hemorrhage.5

CRASH-2 randomized more than 20,000 patients to TXA infusion or placebo. In that trial, a small overall mortality difference was observed— all-cause mortality at four weeks post-injury was 14.5 percent in those treated with TXA compared to 16.0 percent of those treated with placebo. Subgroup analyses of the results indicated a mortality benefit was only observed in the two-thirds of the trial cohort treated within three hours of injury. Thus, the common practice of timely administration of TXA in trauma was born—early administration in suspected or confirmed hemorrhage.

Implementation has been varied. Some institutions limit its use to patients exhibiting objective evidence of excessive fibrinolysis on thromboelastography (TEG) testing. Overall, TXA is considered safe and efficacious.

Since CRASH-2, a variety of further applications for TXA have been investigated, ranging from melasma to epistaxis to angioedema. However, the most prominent investigations remain in the realm of life-threatening hemorrhage. Two years ago, the WOMAN trial was published, investigating its use in postpartum hemorrhage. This trial was conducted primarily in sub-Saharan Africa and south Asia, representative of the resource-scarce settings in which 99 percent of deaths from postpartum hemorrhage occur. In another massive undertaking, more than 20,000 participants were enrolled. The primary outcome was a composite of death from any cause or hysterectomy within six weeks. Unfortunately, neither this composite primary outcome nor the overall risk of death were decreased by administration of TXA, with an absolute difference in both endpoints of 0.3 percent.

Adventuring through subgroup analyses, again in those treated within three hours, the authors teased out and highlighted a favorable secondary outcome: death due to bleeding. In this analysis, the absolute difference in endpoints expanded to 0.5 percent, favoring TXA administration. This effect size finally attained the Holy Grail of statistical significance and became the focus of the authors’ discussion and subsequent media spin.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

No Responses to “What the Data Say about TXA as for Trauma”