Tranexamic acid (TXA) seems to have many uses. But where do we stand on the evidence?

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 38 – No 12 – December 2019The last time we visited the breaking literature regarding TXA, it was to examine the World Maternal Antifibrinolytic (WOMAN) trial.1 That trial generated newspaper headlines, such as “Inexpensive Drug Prevents Deaths in New Mothers, Study Finds” in The New York Times.2 On cursory glance, however, the WOMAN trial was actually a negative trial with regard to the primary outcome.

TXA recently made the news again as the results of the Clinical Randomization of an Antifibrinolytic in Significant Head Injury (CRASH-3) trial were revealed.3 With headlines in The Guardian stating “Drug Could Prevent Thousands of Head Injury Deaths,” surely this couldn’t be yet another negative trial, could it?4

Amazingly enough, it is.

Background

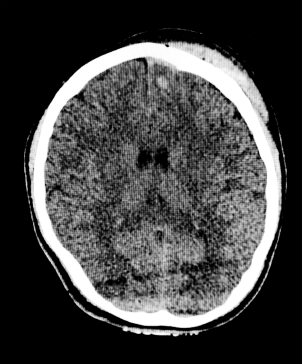

Shutterstock/AndaPhoto.

CT scan of subdural hematoma and intracranial hemorrhage.

Tranexamic acid is a staple of traumatology. It is on the World Health Organization’s list of essential medicines. It has been around since the 1960s, initially designed as treatment for menorrhagia. It can be bought over the counter for this purpose in Europe.

A synthetic analogue of the amino acid lysine, TXA binds to plasminogen, preventing conversion to plasmin and subsequent fibrin degradation. TXA became prominently used in many clinical practices following the CRASH-2 trial, which tested its efficacy in trauma patients with either significant hemorrhage or risk for significant hemorrhage.5

CRASH-2 randomized more than 20,000 patients to TXA infusion or placebo. In that trial, a small overall mortality difference was observed— all-cause mortality at four weeks post-injury was 14.5 percent in those treated with TXA compared to 16.0 percent of those treated with placebo. Subgroup analyses of the results indicated a mortality benefit was only observed in the two-thirds of the trial cohort treated within three hours of injury. Thus, the common practice of timely administration of TXA in trauma was born—early administration in suspected or confirmed hemorrhage.

Implementation has been varied. Some institutions limit its use to patients exhibiting objective evidence of excessive fibrinolysis on thromboelastography (TEG) testing. Overall, TXA is considered safe and efficacious.

Since CRASH-2, a variety of further applications for TXA have been investigated, ranging from melasma to epistaxis to angioedema. However, the most prominent investigations remain in the realm of life-threatening hemorrhage. Two years ago, the WOMAN trial was published, investigating its use in postpartum hemorrhage. This trial was conducted primarily in sub-Saharan Africa and south Asia, representative of the resource-scarce settings in which 99 percent of deaths from postpartum hemorrhage occur. In another massive undertaking, more than 20,000 participants were enrolled. The primary outcome was a composite of death from any cause or hysterectomy within six weeks. Unfortunately, neither this composite primary outcome nor the overall risk of death were decreased by administration of TXA, with an absolute difference in both endpoints of 0.3 percent.

Adventuring through subgroup analyses, again in those treated within three hours, the authors teased out and highlighted a favorable secondary outcome: death due to bleeding. In this analysis, the absolute difference in endpoints expanded to 0.5 percent, favoring TXA administration. This effect size finally attained the Holy Grail of statistical significance and became the focus of the authors’ discussion and subsequent media spin.

CRASH-3 Results

The presentation of CRASH-3 is perplexingly more of the same. Although CRASH-2 investigated TXA’s use for major trauma and extracranial bleeding, CRASH-3 evaluated its use for intracranial hemorrhage. Originally designed to detect overall mortality within 28 days, the study was changed following publication of CRASH-2 to focus on head injury–related death, and then was expanded to ensure an adequate sample could be enrolled and treated within the crucial first three hours. However, like the WOMAN trial before it, neither the results for the original primary outcome nor the modified primary outcome reached statistical significance.

Again, however, the authors expend but a few words acknowledging their original primary outcome. Nor do they pour much mention upon the observed increase in non-head injury–related deaths associated with TXA treatment. Instead, as with the WOMAN trial, the authors dive into the subgroups for head injury–related death, further stratifying those results by Glasgow Coma Scale (CGS).

Within the 12,000 patients randomized, only 4,500 had GCS scores of 9–15 and were treated within three hours. In this subgroup alone, the authors report beneficial effects from TXA administration, with a reduction in head injury–related death from 7.5 percent to 5.8 percent. This subgroup alone forms the foundation of the authors’ discussion and the subsequent coverage in the popular press.

And what of adverse events? In all these studies, the authors confidently state no differences were observed between TXA and placebo. Although technically true, these trials were not specifically powered to detect differences in many infrequent outcomes. For example, in both the WOMAN and CRASH-2 trials, there were more deaths in the group of patients treated with TXA after the three-hour time window, indicating there are clearly some difficult-to-detect harms associated with the use of TXA. When only small benefits in a subgroup are touted as the positive outcome, even a handful of excess adverse events may be important signals.

CRASH-3 is not the only recent trial that assessed the utility of TXA for intracerebral hemorrhage. A smaller trial, Tranexamic Acid for Hyperacute Primary Intracerebral Hemorrhage (TICH-2), randomized 2,325 patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage to either TXA or placebo.6 This trial was unable to reliably detect a difference favoring TXA. However, as with WOMAN and CRASH-3, overall trends and secondary outcome measures generally favored the TXA cohort, albeit the true absolute difference is likely to remain vanishingly small.

So clearly the data do not fully jibe with the findings promoted in the lay press. Where does that leave us when making a bedside decision on TXA use? The overall effect of TXA administration in a subset of patients with head injury is most likely to be positive with respect to head injury–related mortality. This is not inconsequential. However, there are wide confidence intervals and uncertainty resulting from the overall survival observations, and the number of patients needed to treat to save one life may be hundreds of patients or more. Meanwhile, the points the various authors of these studies make are true: This treatment is relatively inexpensive, and the rate of serious adverse events is low enough as to be challenging to detect.

The bottom line, unsatisfyingly enough, is uncertainty. There is clearly room for individual practice variation with no obviously right answer. When considering the use of TXA for intracerebral hemorrhage, at the least it must be given as early as possible and within three hours, targeted at those with mild to moderate head injury, and only after the other higher-yield clinical interventions have been performed.

The opinions expressed herein are solely those of Dr. Radecki and do not necessarily reflect those of his employer or academic affiliates.

References

- WOMAN trial collaborators. Effect of early tranexamic acid administration on mortality, hysterectomy, and other morbidities in women with post-partum haemorrhage (WOMAN): an international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10084):2105-2116.

- McNeil DG. Inexpensive drug prevents deaths in new mothers, study finds. The New York Times. Apr 26, 2017. Accessed Nov. 21, 2019.

- CRASH-3 trial collaborators. Effects of tranexamic acid on death, disability, vascular occlusive events and other morbidities in patients with acute traumatic brain injury (CRASH-3): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10210):1713-1723.

- Davis N. Common drug could prevent thousands of head injury deaths. The Guardian. Oct. 14, 2019. Accessed Nov. 21, 2019.

- Shakur H, Roberts I, Bautista R, et al. Effects of tranexamic acid on death, vascular occlusive events, and blood transfusion in trauma patients with significant haemorrhage (CRASH-2): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9734):23-32.

- Sprigg N, Flaherty K, Appleton JP, et al. Tranexamic acid for hyperacute primary intracerebral haemorrhage (TICH-2): an international randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 superiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10135):2107-2115.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “What the Data Say about TXA as for Trauma”