Explore This Issue

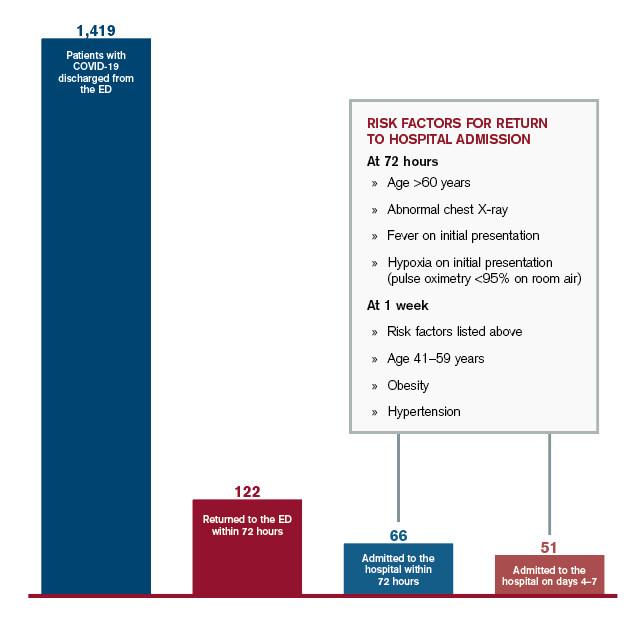

ACEP Now: Vol 39 – No 11 – November 2020Figure 1: Outcomes for COVID-19 Patients Discharged from the ED

Credit: Austin Kilaru

We also found that certain characteristics conferred higher risk for returning to the hospital. While it was not surprising that age was a risk factor, the increase in risk was dramatic—the probability of patients older than age 60 returning for admission was 9 percent, more than three times the rate for patients ages 18–39. We found that patients with abnormal findings on chest X-ray, such as pneumonia, had double the probability of returning, as did patients who initially presented with fever or hypoxia (defined as pulse oximetry less than 95 percent on room air). Obesity, hypertension, and age (ages 41–59) were also risk factors for returning within one week.

These results do not suggest that emergency clinicians are making incorrect decisions in sending patients home, although caution is certainly warranted for patients with multiple risk factors. Rather, the data imply that our initial evaluations are a single snapshot in time for an evolving and somewhat unpredictable process.

Most patients will get better. Some need more help. And for those who do not recover on their own, we need to ensure they do not delay their return so that treatments are more effective. But how can we monitor patients outside the hospital without overwhelming the outpatient care system, particularly when the transition of patients from the emergency department is already fraught with challenges?

What Can We Do?

One type of solution has been demonstrated at our own health system through a program called COVID Watch.6 Patients who go home from the emergency department are enrolled in a text message–based system to perform automated twice-daily check-ins, connect patients with trained clinicians if they have worsening symptoms, and advise returning to the hospital if necessary. Higher-risk patients also receive pulse oximeters to monitor oxygen levels at home.

Caring for this entirely new illness requires emergency clinicians and patients to navigate uncertainty, even beyond our normal practice. We have come a long way in the past several months. To continue to improve—and to help patients even when they are not in the hospital or clinic—we must improve our ability to communicate and coordinate care, requiring innovation and change on a population level, beyond our approach to individual patients.

Dr. Kilaru is adjunct assistant professor of emergency medicine at Philadelphia VA Medical Center and the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

Dr. Kilaru is adjunct assistant professor of emergency medicine at Philadelphia VA Medical Center and the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

No Responses to “What To Expect When Sending Patients with COVID-19 Home”