We have learned much about the novel coronavirus in the months since the start of the pandemic. But one of the major questions is one that we normally are quite comfortable with as emergency physicians: Who can be discharged, and who must be hospitalized?

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 39 – No 11 – November 2020While we are becoming more familiar with the risk factors for severe COVID-19 illness, including age and certain preexisting conditions, that is not the same as knowing who to admit and who to send home.

A problem noted from early in the pandemic is that some patients worsen many days after initially developing symptoms.1 Delays in deterioration can occur with other viral illnesses but not with the characteristic pattern of COVID-19.2 The common adage for mildly or moderately ill patients with influenza or stomach virus—“You’ll start to feel better in a few days”—may not apply. Despite known risk factors, young and healthy people can still get very sick without explanation, even after “turning the corner,” and others have symptoms that persist for weeks and months.3

While we are skilled in providing lifesaving care to patients with critical illness, a different challenge arises when we provide guidance and reassurance to patients who truly are sick, may indeed have early but serious disease, but are stable and do not require any services that hospitalization uniquely provides.

COVID Bouncebacks

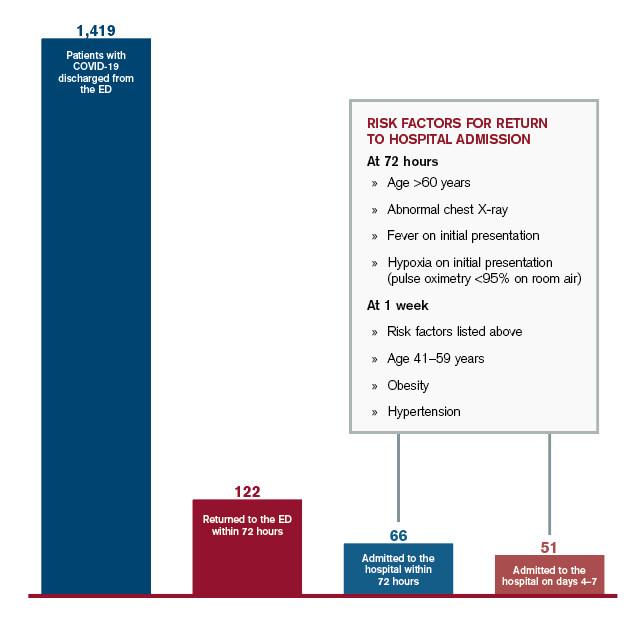

For this reason, our team studied COVID-19 patients who return to the hospital after an initial evaluation in the emergency department.4 The goal was to understand how often people need hospitalization after initially appearing well enough to recover at home, as well as to identify which patients tend to worsen to the point of needing hospitalization and when that might occur. We analyzed the outcomes of 1,419 patients with COVID-19 who were evaluated and discharged from five hospital emergency departments from March through May.

The results (see Figure 1) have implications for clinicians seeking to counsel patients as well as health systems seeking to monitor the progress of patients with COVID-19. Overall, nearly 5 percent of patients returned within 72 hours and needed admission to the hospital. For context, this rate may be five times higher than that described for all ED patients.5 An additional 3.5 percent of patients needed admission within one week. The fact that patients were hospitalized on their second visit indicates that their illness and symptoms progressed to the point where they needed a higher level of support than they could receive at home, such as oxygen, therapeutic medications, or treatments for other chronic conditions that may have been exacerbated.

Figure 1: Outcomes for COVID-19 Patients Discharged from the ED

Credit: Austin Kilaru

We also found that certain characteristics conferred higher risk for returning to the hospital. While it was not surprising that age was a risk factor, the increase in risk was dramatic—the probability of patients older than age 60 returning for admission was 9 percent, more than three times the rate for patients ages 18–39. We found that patients with abnormal findings on chest X-ray, such as pneumonia, had double the probability of returning, as did patients who initially presented with fever or hypoxia (defined as pulse oximetry less than 95 percent on room air). Obesity, hypertension, and age (ages 41–59) were also risk factors for returning within one week.

These results do not suggest that emergency clinicians are making incorrect decisions in sending patients home, although caution is certainly warranted for patients with multiple risk factors. Rather, the data imply that our initial evaluations are a single snapshot in time for an evolving and somewhat unpredictable process.

Most patients will get better. Some need more help. And for those who do not recover on their own, we need to ensure they do not delay their return so that treatments are more effective. But how can we monitor patients outside the hospital without overwhelming the outpatient care system, particularly when the transition of patients from the emergency department is already fraught with challenges?

What Can We Do?

One type of solution has been demonstrated at our own health system through a program called COVID Watch.6 Patients who go home from the emergency department are enrolled in a text message–based system to perform automated twice-daily check-ins, connect patients with trained clinicians if they have worsening symptoms, and advise returning to the hospital if necessary. Higher-risk patients also receive pulse oximeters to monitor oxygen levels at home.

Caring for this entirely new illness requires emergency clinicians and patients to navigate uncertainty, even beyond our normal practice. We have come a long way in the past several months. To continue to improve—and to help patients even when they are not in the hospital or clinic—we must improve our ability to communicate and coordinate care, requiring innovation and change on a population level, beyond our approach to individual patients.

Dr. Kilaru is adjunct assistant professor of emergency medicine at Philadelphia VA Medical Center and the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

Dr. Kilaru is adjunct assistant professor of emergency medicine at Philadelphia VA Medical Center and the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

Dr. Lee is director of innovation and assistant professor of clinical emergency medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

Dr. Lee is director of innovation and assistant professor of clinical emergency medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

References

- Interim clinical guidance for management of patients with confirmed coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed June 1, 2020.

- Gandhi RT, Lynch JB, Del Rio C. Mild or moderate Covid-19 [published online ahead of print April 24, 2020]. N Engl J Med. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp2009249.

- Tenforde MW, Kim SS, Lindsell CJ, et al. Symptom duration and risk factors for delayed return to usual health among outpatients with COVID-19 in a multistate health care systems network – United States, March-June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:993-998.

- Kilaru AS, Lee K, Snider CK, et al. Return hospital admissions among 1419 COVID-19 patients discharged from five U.S. emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27(10):1039-1042.

- Cheng J, Shroff A, Khan N, et al. Emergency department return visits resulting in admission: do they reflect quality of care? Am J Med Qual. 2016;31(6):541-551.

- Morgan AU, Balachandran M, Do D, et al. Remote monitoring of patients with Covid-19: cesign, implementation, and outcomes of the first 3,000 patients in COVID Watch. NEJM Catal Innov Care Deliv. 2020;10.1056/CAT.20.0342.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “What To Expect When Sending Patients with COVID-19 Home”