A 39-year-old male presents to your emergency department (ED) with complaints of a headache after a roll-over motor vehicle accident. He was a restrained driver traveling 65 miles per hour on the highway when he lost control in the rain, hit a guardrail, and had a brief loss of consciousness. His only medical history is hypertension and does not take any anticoagulation. He has a normal neurological exam with a glasgow coma scale (GCS) of 15. Due to the mechanism of injury, a head CT was obtained. The patient was found to have a small intraparenchymal hemorrhage. Neurosurgery was consulted at the regional trauma center where the consultant recommended observing the patient in the ED with a repeat head CT in six hours. Should you do it or should you look for another transferring facility?

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 43 – No 04 – April 2024Background

Patients who are found to have traumatic intracranial hemorrhages (tICHs) are frequently transferred for neurosurgical evaluation.1,2 Patients with isolated mild tICH typically do not experience neurological deterioration nor undergo neurosurgical intervention. The vast majority of mild tICH patients can be discharged within 24 hours including from the ED.1 Transferring these patients can lead to unnecessary costs, strain on the health care system, and inconvenience to patients and families who have to travel far distances without accruing any added benefit. Unnecessary transfers can also worsen bed shortages, lead to emergency department crowding, and worsen hospital boarding at trauma centers. This ultimately delays care for other patients who may benefit from a transfer. Recent studies have started to look at identifying patients with an isolated tICH who do not need intensive monitoring or intervention and could be discharged from the ED after a short period of observation.

Evidence

Click to enlarge.

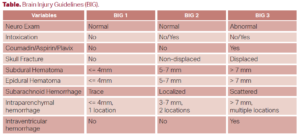

Several tools have been evaluated to risk stratify patients with mild tICHs for deterioration and neurosurgical intervention. The first is the Brain Injury Guidelines (BIG), which looked at various factors to risk stratify patients into three categories (see Table). In their multi-center validation study of 2033 patients, they found that patients who were classified as BIG 1 and BIG 2 (around 30 percent of all patients) had zero TBI-related post-discharge ED visits or 30-day readmissions. BIG 1 patients (around 15 percent of patients) also did not require repeat neuroimaging or neurosurgical consultation. They were discharged from the ED after only six hours of observation.3

The SafeSDH tool defined low risk patients as those who had none of the following: taking anticoagulation or clopidogrel, more than one discrete type of hematoma, subdural hematoma (SDH) greater than 5 mm, midline shift, and GCS less than 14. The primary composite outcome included not only the need for neurosurgical intervention (both immediate and delayed), but also any neurological decline and death. In a validation study of 753 patients at 6 hospitals (including both trauma and non-trauma centers), 21.5 percent of patients were deemed low risk. Sensitivity of the tool was 99 percent and a negative predictive value of 0.03. Only two cases fell out due to neurological decline which were felt to be related to medical reasons and not from the SDH. Repeat neuroimaging showed no change in the size of the SDH and no neurosurgical intervention was required.1

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

No Responses to “When Can You Discharge Traumatic Intracranial Hemorrhage from the Emergency Department?”