Explore This Issue

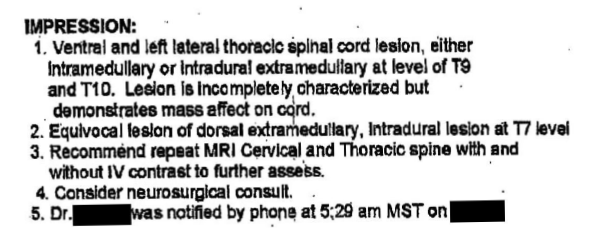

ACEP Now: Vol 38 – No 12 – December 2019Figure 2: The physician’s notes following the patient’s fourth ED visit.

A neurosurgeon was promptly consulted, and they took the patient to the operating room for surgical decompression. The patient did not recover use of his legs and is paraplegic.

Off to the Courts

The patient contacted a plaintiff’s attorney. A lawsuit was filed against each of the emergency physicians as well as the hospital. Extensive negotiations were held as the lawsuit progressed, and three days before the case was scheduled to go to a jury trial, a settlement was reached. The settlement is confidential but generally would be expected to be at least several million dollars (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: The newly paraplegic patient sued each of his emergency physicians as well as the hospital.

This case represents an unfortunately common malpractice theme in emergency medicine. A patient is seen multiple times with vague symptoms and eventually develops neurological symptoms. The patient is ultimately diagnosed with SEA and suffers permanent disability.

These cases are why plaintiff’s attorneys exist. A delay in care that leaves a patient with severe disability that will require a lifetime of care is a reasonable trigger for a legal remedy, even if those delays in care would have been extremely hard for a physician to predict on the initial visits. But based on the devastating outcomes, it is easy to see why juries are enormously sympathetic to such plaintiffs and why these cases often lead to large settlements or awards.

What went wrong here? A critical issue in the diagnosis of SEA is the availability of MRI. There is wide variation in how easily an emergency medicine physician can order an MRI, ranging from clicking a few buttons to arguing with an on-call specialist to transferring a patient to another facility. Obtaining an MRI can be a lengthy endeavor in hospitals that do not have clear and easy protocols to allow for rapid imaging, further delaying their definitive care.

Unfortunately, individual physicians may be left to bear the liability in these situations, despite the reality that such systems-level problems are not of their own making.

Right Diagnosis, Wrong Location

In this case, the diagnosis was considered early in the patient’s fourth ED visit, once neurological symptoms had developed. However, even then imaging at the wrong level of the spine was ordered, further delaying his care. This is a mistake that has occurred in multiple SEA malpractice cases I have read. In these cases, the most common mistake is ordering imaging of the lumbar spine, missing the true location of the lesion in the thoracic or cervical spine.

There are two key tips emergency physicians can use to avoid similar situations, both centered around the physical exam. Although a screening neurological exam is appropriate for many ED patients, a cursory exam is not acceptable if the physician is concerned enough about SEA to order an MRI.

The easiest way to address this and not miss key findings is to perform a thorough sensory exam. Although the exact anatomy of the myotome and associated nerves may prove challenging to remember, the dermatome level is easily testable and can be compared to a chart you can find rapidly with a Google search.

Localizing a suspected lesion based on the dermatome will lead the clinician to the appropriate anatomical segment of the spine to image. Many physicians feel an MRI to rule out SEA should always include the entire spine, though this is not evidence-based and there are downsides to this approach (see below). It is not always possible to predict the anatomical region of the lesion based on exam alone.

When the physical exam does not clearly localize the lesion, that may suggest a lesion close to the border between two anatomical segments (or the patient may be providing conflicting information). In these cases, it is certainly best to image the entire spine. This is also important given that patients may have multiple abscesses. Multilevel disease is most common in patients who have a hematogenous spread of infection as the cause of their abscess.

That said, obtaining an MRI with contrast of the patient’s entire cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine will take hours and likely be met by pushback from MRI staff. Calling staff before placing the order and giving a brief explanation will save time and help stave off antagonism.

Spinal epidural abscesses can be very difficult for clinicians to diagnose and can lead to devastating patient outcomes. In the early stages of the disease, nonspecific symptoms predominate. During the later course of the disease, when physicians likely have a high suspicion for SEA, careful attention should be given to obtaining a thorough exam to guide imaging decisions. Use of the sensory exam dermatome level or imaging the entire spine will help avoid the heartbreaking situation of making the right diagnosis at the wrong location.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

No Responses to “When Delayed Diagnosis Leads to a Malpractice Lawsuit”