Patients presenting to the emergency department with multiple vague and nonspecific symptoms pose a particular diagnostic challenge. Generally, these presentations do not result in discovery of any severe issues, but periodically, they herald the onset of a sinister and hidden emergency disease. Multiple return visits give the emergency physician an opportunity to rethink the situation with the benefit of further information.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 38 – No 12 – December 2019The below medical malpractice lawsuit highlights a patient presenting with vague complaints over multiple visits, leading to a bad outcome from a diagnosis that is a well-known medicolegal risk.

The Case

A 36-year-old man presented to an urgent care with a dry cough, body aches, and general malaise. He was seen by a physician, who did not order any testing and discharged him with generic instructions to take Tylenol and ibuprofen.

Two days later, the patient’s symptoms persisted, and he presented to a local emergency department. The documentation from this visit notes he was also complaining of back pain and neck stiffness. An aggressive workup was ordered, including a complete blood count, a comprehensive metabolic panel, mononucleosis testing, urinalysis, an ECG, and a chest X-ray.

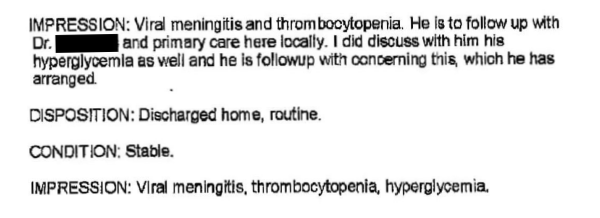

The results showed thrombocytopenia of 61,000 and a glucose of 245. Given the patient’s neck stiffness, a lumbar puncture was recommended. The cerebrospinal fluid results did not show any abnormal findings. The patient was ultimately discharged with a diagnosis of viral meningitis, thrombocytopenia, and hyperglycemia (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The physician’s notes following the patient’s first ED visit.

Over the next few days, the patient continued to feel worse. His malaise progressed, and his back pain also worsened. He presented back to the emergency department. His platelet count had improved to 120,000. A lactate was in the normal range. He was prescribed Percocet and Soma, then discharged again.

Following his third discharge, he began to experience weakness and numbness in his legs. He returned to the emergency department for a fourth time. The emergency physician reviewed his case and appropriately recognized the patient was showing signs of a spinal cord syndrome. Therefore, an MRI of his lumbar spine was ordered.

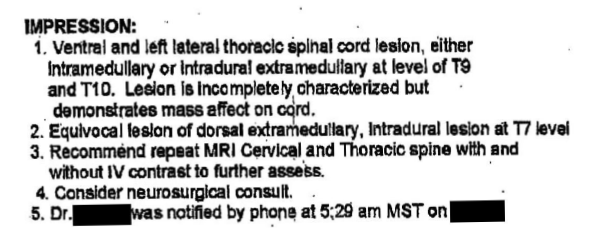

The results of the lumbar spine MRI did not show any acute abnormalities. Given the patient’s objective neurological deficits, he was admitted to the hospital. Eventually, a thoracic MRI was ordered as well. The results showed a spinal epidural abscess (SEA) at T9/T10 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: The physician’s notes following the patient’s fourth ED visit.

A neurosurgeon was promptly consulted, and they took the patient to the operating room for surgical decompression. The patient did not recover use of his legs and is paraplegic.

Off to the Courts

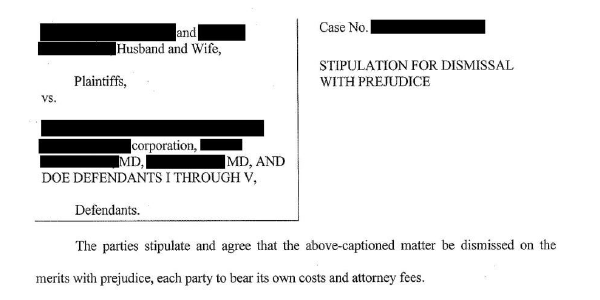

The patient contacted a plaintiff’s attorney. A lawsuit was filed against each of the emergency physicians as well as the hospital. Extensive negotiations were held as the lawsuit progressed, and three days before the case was scheduled to go to a jury trial, a settlement was reached. The settlement is confidential but generally would be expected to be at least several million dollars (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: The newly paraplegic patient sued each of his emergency physicians as well as the hospital.

This case represents an unfortunately common malpractice theme in emergency medicine. A patient is seen multiple times with vague symptoms and eventually develops neurological symptoms. The patient is ultimately diagnosed with SEA and suffers permanent disability.

These cases are why plaintiff’s attorneys exist. A delay in care that leaves a patient with severe disability that will require a lifetime of care is a reasonable trigger for a legal remedy, even if those delays in care would have been extremely hard for a physician to predict on the initial visits. But based on the devastating outcomes, it is easy to see why juries are enormously sympathetic to such plaintiffs and why these cases often lead to large settlements or awards.

What went wrong here? A critical issue in the diagnosis of SEA is the availability of MRI. There is wide variation in how easily an emergency medicine physician can order an MRI, ranging from clicking a few buttons to arguing with an on-call specialist to transferring a patient to another facility. Obtaining an MRI can be a lengthy endeavor in hospitals that do not have clear and easy protocols to allow for rapid imaging, further delaying their definitive care.

Unfortunately, individual physicians may be left to bear the liability in these situations, despite the reality that such systems-level problems are not of their own making.

Right Diagnosis, Wrong Location

In this case, the diagnosis was considered early in the patient’s fourth ED visit, once neurological symptoms had developed. However, even then imaging at the wrong level of the spine was ordered, further delaying his care. This is a mistake that has occurred in multiple SEA malpractice cases I have read. In these cases, the most common mistake is ordering imaging of the lumbar spine, missing the true location of the lesion in the thoracic or cervical spine.

There are two key tips emergency physicians can use to avoid similar situations, both centered around the physical exam. Although a screening neurological exam is appropriate for many ED patients, a cursory exam is not acceptable if the physician is concerned enough about SEA to order an MRI.

The easiest way to address this and not miss key findings is to perform a thorough sensory exam. Although the exact anatomy of the myotome and associated nerves may prove challenging to remember, the dermatome level is easily testable and can be compared to a chart you can find rapidly with a Google search.

Localizing a suspected lesion based on the dermatome will lead the clinician to the appropriate anatomical segment of the spine to image. Many physicians feel an MRI to rule out SEA should always include the entire spine, though this is not evidence-based and there are downsides to this approach (see below). It is not always possible to predict the anatomical region of the lesion based on exam alone.

When the physical exam does not clearly localize the lesion, that may suggest a lesion close to the border between two anatomical segments (or the patient may be providing conflicting information). In these cases, it is certainly best to image the entire spine. This is also important given that patients may have multiple abscesses. Multilevel disease is most common in patients who have a hematogenous spread of infection as the cause of their abscess.

That said, obtaining an MRI with contrast of the patient’s entire cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine will take hours and likely be met by pushback from MRI staff. Calling staff before placing the order and giving a brief explanation will save time and help stave off antagonism.

Spinal epidural abscesses can be very difficult for clinicians to diagnose and can lead to devastating patient outcomes. In the early stages of the disease, nonspecific symptoms predominate. During the later course of the disease, when physicians likely have a high suspicion for SEA, careful attention should be given to obtaining a thorough exam to guide imaging decisions. Use of the sensory exam dermatome level or imaging the entire spine will help avoid the heartbreaking situation of making the right diagnosis at the wrong location.

See the Records from This Case

Read the entire medical record from this case and see additional legal documents.

Dr. Funk is a practicing emergency medicine physician in Springfield, Missouri, and owner of Med Mal Reviewer, LLC. He writes about medical malpractice.

Dr. Funk is a practicing emergency medicine physician in Springfield, Missouri, and owner of Med Mal Reviewer, LLC. He writes about medical malpractice.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “When Delayed Diagnosis Leads to a Malpractice Lawsuit”