The best questions often stem from the inquisitive learner. As educators, we love—and are always humbled—by those moments when we get to say “I don’t know.” For some of these questions, you may already know the answers. For others, you may never have thought to ask the question. For all, questions, comments, concerns, and critiques are encouraged. Welcome to the Kids Korner.

Explore This Issue

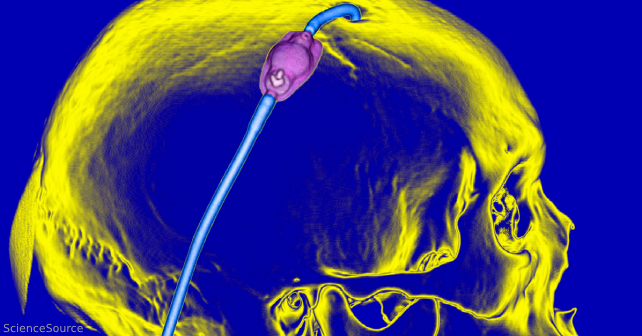

ACEP Now: Vol 43 – No 11 – November 2024In children with ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunts, when is the most common time for the shunt to fail?

Children with and without VP shunts get sick. When a child with a VP shunt develops a fever or feels unwell, the voice in the back of our heads asks, “Is it the shunt?” Sometimes it is; most often it’s not. While we often evaluate the shunt for malfunction, is there a particular time window where shunt malfunction is more common?

To begin, a 2012 prospective pediatric study found a failure rate of 16.9 percent.1 It was a five-year prospective study at a single institution and followed 236 children under 12 years of age who received VP shunts—40 children (16.9 percent) required shunt revision. In these 40 children, there were 48 shunt revisions, meaning some children had more than a single shunt revision. The most common complications leading to shunt revision were peritoneal end malfunction (n=18), shunt/shunt tract infection (n=7), extrusion of peritoneal catheter through the anus (n=5), ventricular end malfunction (n=4), and cerebrospinal (CSF) leak from the abdominal wound (n=4). In these children requiring shunt revision, 38 (79 percent) occurred within six months of previous surgery and 28 (58 percent) occurred within three months of the previous surgery. There were four (8 percent) who required revision within six–12 months and six children (12.5 percent) required revision after one year of prior surgery. While a shunt complication can occur at any time period, the majority of VP shunt malfunctions requiring revision occurred within the first six months following placement. A 10-year retrospective observational study by the same author again evaluated children younger than 12 years of age who had received VP shunts.2 This was a different group of children evaluated at a later time period at the same institution. The author found the VP shunt revision rate to be 11.9 percent (40 of 336 children). Similarly, 70 percent of VP revisions occurred within the first six months after surgery.

A 2016 multicenter prospective study evaluated 1,036 pediatric patients for shunt failure who received CSF shunts over a four-year period.3 This study was conducted at six institutions in the Hydrocephalus Clinical Research Network. Inclusion criteria included children younger than 19 years of age undergoing their first insertion of a CSF shunt for the treatment of hydrocephalus. Nearly all shunts were VP shunts. The majority of patients were younger than six months of age at time of initial shunt placement (55.7 percent) for hydrocephalus. During that study period, 344 (33 percent) shunts failed. Risk factors associated with shunt failure were: patient age younger than six months (adjusted HR 1.4; 95 percent CI 1.1–2.1); cardiac comorbidity (adjusted HR 1.4; 95 percent CI 1.0–2.1); and interoperative use of the endoscope (adjusted HR 1.9; 95 percent CI 1.2–2.9). Specifically, regarding shunt failure, the mean time of failure was 344 days (range 1–932 days). While the authors do not specifically state the highest risk time for failure, the mean and range suggest that the majority of these cases failed within the first year after being placed.

Pages: 1 2 | Single Page

No Responses to “When Do Pediatric Ventriculoperitoneal Shunts Fail?”