Intermountain Medical Center, flagship hospital of the health system by the same name, sits nestled along the Wasatch Mountains in Utah. It is a bright, modern urban medical center, a tertiary teaching hospital, a transplant center, and a Level One Trauma Center. The emergency department sees 90,000 visits per year in its 75 beds. In short, it has the characteristics of an emergency department that should struggle with efficiency and performance.

Intake room. (Image courtesy of Adam Balls, MD, and Brian Oliver, MD.)

However, in 2015, it was already performing very well compared to emergency departments in its cohort. Overall median lengths of stay (LOS) were 207 minutes, door to provider (Door to Doc) times were consistently under 30 minutes, and the left without being seen (LWBS) rate was 2.4 percent. By comparison, according to the Emergency Department Benchmarking Alliance, the median overall LOS for hospitals of this size is 227 minutes, Door to Doc is 32 minutes, and LWBS is 3.1 percent. Despite very strong operational metrics, the quality-minded doctors (Utah Emergency Physicians) led by the director and assistant director, Adam Balls, MD, and Brian Oliver, MD, were tasked with reengineering their ED flow. In preparation for the current changing health care imperatives, the hospital leadership wished to open up an observation unit within the emergency department. The only way this would be possible would be to put physicians in triage and move to a vertical flow model, no longer bedding every patient. This model has also been shown to deliver improvements in the efficiency of care delivered to lower-acuity patients.

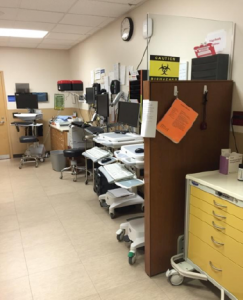

Results waiting area. (Image courtesy of Adam Balls, MD, and Brian Oliver, MD.)

Adapting a version of Jody Crane’s AcceleratED flow model (which is a version of the team triage model that keeps patients vertical and brings the staff and supplies to patients), the ED leaders reinvented their patient flow and workflow. The concept is that many patients can be completely evaluated and treated without occupying an ED bed. They arrive and remain ambulatory, and resources are brought to them. The model involves careful selection of which patients can be appropriately treated in this manner. This was a project that turned on a dime. With a one-week rapid-cycle testing phase, the project was off and running. Moving to a vertical patient flow model is one of the easiest improvements to introduce in the emergency department with regard to implementation.

Patient flow now looks like this: A highly trained and experienced “greeter nurse” does rapid, abbreviated triage, mostly for the purpose of deciding whether patients are appropriate for the AcceleratED model or traditional bed placement. If criteria are met, patients are streamed to the AcceleratED area and “swarmed” by a team. Patients tell their story once, and the assessment and workup are begun in parallel. Patients may need to be briefly bedded for diagnostics, but most of their ED time is spent in a chair in a large, bright, open waiting room. There are two physicians and a nurse practitioner or physician assistant, five nurses, and three techs working in the AcceleratED area during the busiest hours of the day. During low-volume times, the emergency department operates under a pull-to-full traditional ED model.

Strategically placed equipment and supplies. (Image courtesy of Adam Balls, MD, and Brian Oliver, MD.)

The emergency department has four triage rooms, which serve as the AcceleratED space. The team had to bring supplies for point-of-care testing, splints and suturing supplies, and computers to the area to be sure patients could have every step of their care completed out front. The team performed a rapid-cycle testing phase using “A team” physicians who were invested in the success of the initiative and known to be particularly efficient in crafting quick, decisive care plans for patients. They then went live in November. The original implementation plan had been to drop the new process during the holidays, as the emergency department typically sees a 10 percent increase in volume during the week between Christmas and New Year’s. The improvements were so compelling that the leadership at the hospital asked the ED leaders and physicians to continue with the reengineered model.

Dr. Balls is quick to give credit to the administrative leaders at Intermountain Medical Center, who took the leap of faith in providing some quick out-of-budget-cycle funding for small front-end redesigns and enhancements to make the project work. They started in a small, confined workspace, but the results have been remarkable. The project has been so successful that they are supporting space redesigns to allow a more ergonomically friendly space for the team to work in that yields even more gains in efficiency!

The success has been dramatic:

| BEFORE | AFTER | |

|---|---|---|

| Door to Doc | 27 minutes | 19 minutes |

| LOS | 207 minutes | 187 minutes |

| LWBS | 2.4% | 1.2% |

Dr. Oliver and Dr. Balls’ lessons learned from the new flow model:

- Not all physicians are suited for the physician-in-triage role.

- An indecisive physician unable to multitask can create a bottleneck at intake.

- Supplies must be strategically located.

- Patients appropriate for the AcceleratED model can be through the intake process within 35 minutes.

- Paperwork and processing must be streamlined.

- Scribes are a great idea for physicians processing so many patients.

- ED tech staffing is important in this flow model.

- Transport techs are important in this flow model.

- The physician group has to be prepared for many schedule adaptations as the model is improved.

- These are very busy shifts for physicians, and scheduling must be realistic.

Though this busy emergency department would be the envy of many other departments, the physicians and staff set the bar higher and came out of their comfort zone to engage in wholesale change. The payoff? Mountains of improvement!

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

One Response to “Intermountain Medical Center in Utah Improves Efficiency, Performance with Vertical Flow Model”

April 25, 2017

Anna FraserHi there,

Where did you get the Door to Doc, LOS and LWBS statistics from? Do you have a valid source you can pass on to me?

Regards,

Anna