Not too long ago, safety in airway management hinged on two pillars of safety: the first was the ability to mask ventilate, and the second was cricoid pressure (CP).

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 33 – No 11 – November 2014Mask Ventilation

The ability to mask ventilate was perceived to be a required first step in elective airway management before giving muscle relaxants. Multiple anesthesia studies have now shown that muscle relaxation correlates with improvement in mask ventilation, not collapse of the airway as many of us were taught. Warters et al. demonstrated that rocuronium improved mask ventilation in 67 percent of patients, resulted in unchanged ventilation in 33 percent, and made ventilation more difficult in no instance.1

In addition to making mask ventilation easier, muscle relaxation has a second safety benefit—it permits insertion of a supraglottic airway (laryngeal mask airway [LMA] type device, or King LT-D). In the past, difficulty of mask ventilation led to awakening the patient and avoiding rapid sequence intubation; now some anesthesiologists advocate that the response should be the opposite—give muscle relaxants—and improve mask ventilation, insert an LMA, or intubate. Within the anesthesia community, many are questioning whether demonstrating mask ventilation prior to intubation should be abandoned.2,3

In the past, difficulty of mask ventilation led to awakening the patient and avoiding rapid sequence intubation; now some anesthesiologists advocate that the response should be the opposite—give muscle relaxants—and improve mask ventilation, insert an LMA, or intubate.

According to Kheterpal et al., who studied more than 53,000 anesthesia cases, the frequency of impossible ventilation is approximately 1 in 2,800, and only one in four of those with impossible ventilation were difficult to intubate.4 The LMA works in 95 percent of instances of difficult or impossible mask ventilation.5

Combining optimal mask ventilation (with muscle relaxants) with an LMA and intubation (direct/video laryngoscopy with passive apneic oxygenation) makes use of muscle relaxants very low risk in the hands of skilled operators.

Cricoid Pressure

The second pillar of safety, CP, seems to be fading fast into medical lore. Many studies show CP impedes laryngoscopy, worsens ventilation, and does not prevent regurgitation. The latest advanced cardiovascular life support (ACLS) guidelines no longer recommend its use in cardiac arrest; in other scenarios, ACLS states CP should be released if it impedes intubation or ventilation. A final nail in the coffin, I would argue, is that CP and the LMA are noncompatible. CP prevents LMA placement in the upper esophagus, and if applied after LMA insertion, it will push the LMA out of position.

New Rules: LMA

The LMA has rewritten the rules of airway management. An estimated 2 billion people around the world have had airway management with the LMA. It is now used in about 50 percent of elective general anesthesia cases in the United States and more than 90 percent in the United Kingdom. It is universally recognized as an essential backup device in airway management in any setting.

The LMA requires a deep level of anesthesia (with propofol, usually), an absent gag reflex, or muscle relaxation with neuromuscular agents. In this world of new devices and rewritten rules, we now have the “rapid sequence airway.” The term was coined by Darren Braude, MD, who is an airway educator, enthusiast, and EMS director based in New Mexico. Instead of using muscle relaxants to place a tracheal tube, Dr. Braude and his flight crew have used muscle relaxants to insert a supraglottic airway (ie, a King LT-D). A similar technique has been adopted by David Duncan, MD, medical director at CALSTAR, which is a helicopter and fixed-wing service with nine bases in California. CALSTAR combines muscle relaxants on scene with insertion of a Cookgass air-Q (an LMA type device; he uses the new air-Q SP version, with a self-pressurizing cuff). Intubation can then be accomplished by the flight crew en route to the hospital if time permits. The Cookgas air-Q has significantly reduced the on-scene time for CALSTAR’s trauma patients.

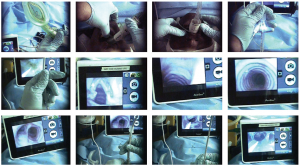

In the ED, Andy Sloas, DO, an emergency physician at the University of Kentucky in Lexington, has been using LMAs after administration of muscle relaxants for years. Once ventilation and oxygenation are stabilized, he uses the LMA as a mucus-free conduit to intubate—combining an endoscope with an Aintree catheter passed via the LMA channel. Though Dr. Sloas’s practice is uncommon in the ED setting, intubation through the LMA with endoscopy is widely done in anesthesia.

Airway management is evolving rapidly; we are beginning to rethink the rules laid down 30 years ago (pre-LMA, pre-video laryngoscopy, pre-nasal oxygen during efforts securing a tube [NO-DESAT] or apneic oxygenation via nasal cannula during intubation). There are now second- and third-generation supraglottic airways, which permit effective ventilation and gastric decompression. Some of these include the Ambu Aura-GAIN, the Cookgas air-Q SP, the Intersurgical i-gel, the LMA Supreme, and the King LT-D. Many of these devices also serve as great conduits for intubation with endoscopes.

Dr. Levitan is an adjunct professor of emergency medicine at Dartmouth College’s Geisel School of Medicine in Hanover, N.H., and a visiting professor of emergency medicine at the University of Maryland in Baltimore. He works clinically at a critical care access hospital in rural New Hampshire and teaches cadaveric and fiber-optic airway courses.

Dr. Levitan is an adjunct professor of emergency medicine at Dartmouth College’s Geisel School of Medicine in Hanover, N.H., and a visiting professor of emergency medicine at the University of Maryland in Baltimore. He works clinically at a critical care access hospital in rural New Hampshire and teaches cadaveric and fiber-optic airway courses.

References

- Warters RD, Szabo TA, Spinale FG, DeSantis SM, Reves JG. The effect of neuromuscular blockade on mask ventilation. Anaesthesa. 2011;66:163-167.

- Calder I, Yentis SM. Could ‘safe practice’ be compromising safe practice? Should anaesthetists have to demonstrate that face mask ventilation is possible before giving a neuromuscular blocker? Anaesthesia. 2008;63:113-5.

- Calder I, Yentis S, Patel A. Muscle relaxants and airway management. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:216-7.

- Kheterpal S, Martin L, Shanks AM, Tremper KK. Prediction and outcomes of impossible mask ventilation: a review of 50,000 anesthetics. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:891-7.

- Parmet JL, Colonna-Romano P, Horrow JC, Miller F, Gonzales J, Rosenberg H. The laryngeal mask airway reliably provides rescue ventilation in cases of unanticipated difficult tracheal intubation along with difficult mask ventilation. Anesth Analg. 1998;87:661-5.

No Responses to “10 Tips for Safety in Airway Management”