This medical malpractice case covers a theme commonly seen in lawsuits against emergency physicians. It highlights the importance of carefully reviewing test results and communicating clearly with patients and other doctors.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 40 – No 03 – March 2021The Case

A 63-year-old man presented with a cough. His vital signs showed a heart rate of 123 bpm, blood pressure of 129/94, respiratory rate of 15/min., and oxygen saturation of 96 percent on ambient air. His past medical history was remarkable for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and a history of smoking. He was seen by a triage nurse, who noted chest congestion for one week as well as fever and chills.

The physician saw the patient and documented similar complaints. He also noted that the patient had body aches and “burning pain” with coughing. The review of systems noted the absence of fever and chills, conflicting with the triage documentation. The physical examination was relevant for diminished breath sounds, unlabored breathing, and the ability to carry on normal conversation.

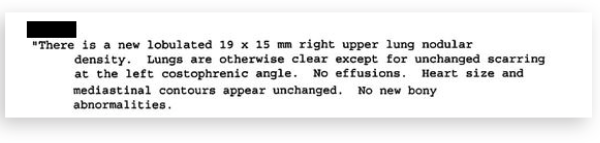

A chest radiograph was ordered, and the patient was treated with DuoNeb (albuterol sulfate and ipratropium bromide). The chest radiograph interpretation is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Chest Radiograph Interpretation

The physician documented an assessment of the cough, upper respiratory infection, and COPD. On reassessment, the patient was described as feeling “OK after visit.” The physician documented that the “chest X-ray shows some residual of COPD with no acute changes.”

The patient was advised to push fluids, use an inhaler, stop dairy, and follow up with his primary care physician (PCP) about the possibility of obtaining a nebulizer for home use.

The patient did not have any documented health care visits for the next three years.

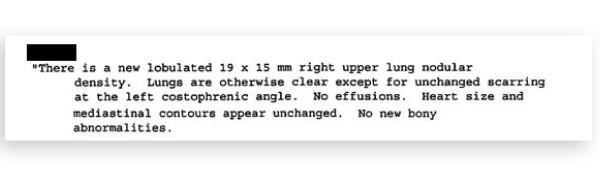

Three years later, he presented to a new PCP to establish care due to the fact that he had been feeling short of breath and fatigued. Labs and a chest radiograph were ordered. The chest radiograph showed a significantly larger lung mass, and he was promptly referred for a CT scan and consultation with a pulmonologist. The CT scan results are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: CT Scan Result

The patient was seen by pulmonology and ultimately had his case presented at the hospital’s tumor review board. He was deemed not to be a surgical candidate but underwent extensive chemotherapy and radiation treatment.

The medical record available in the court case ends with consultations from palliative care specialists. His medical outcome is uncertain, although a search of newspaper records did not turn up an obituary under the patient’s name.

The Lawsuit

Two years after being diagnosed with lung cancer (and five years since the initial emergency department visit), the patient contacted a medical malpractice law firm. A lawsuit was filed against the hospital where the patient was originally seen. The complaint alleged that improper follow-up on the lung mass occurred, allowing it to progress to an inoperable tumor.

In an unusual twist, the physician who originally saw the patient had died prior to the discovery of the lung cancer.

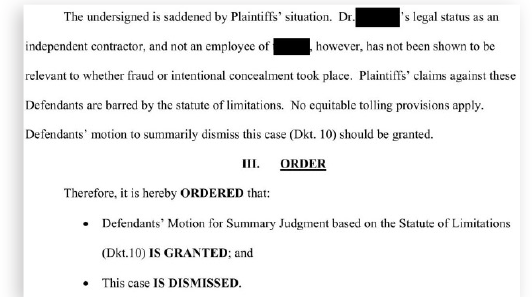

After the lawsuit was filed, the defense filed a motion for summary judgment based on the statute of limitations. The state in which this happened has a three-year limit from the time a negligent act occurs. If the negligence is not discovered within three years, the plaintiff has an additional year to file the lawsuit.

In this instance, the lawsuit was filed two years after the negligence was discovered, therefore falling outside the statute of limitations. The plaintiffs attempted to argue that they should be given additional time because the physician was an independent contractor and not directly employed by the hospital. The judge dismissed the case. The end of his opinion is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Excerpt from the Judge’s Opinion

This case highlights the medicolegal risk associated with incidental findings. This is a common reason for malpractice lawsuits against emergency and urgent care physicians. We are often focused solely on emergency or acute disease processes and can overlook other issues.

In this case, it seems that the error was simply a failure to identify an incidental finding that needed follow-up. In other malpractice cases, incidental findings are often appropriately identified but there is a failure of adequate communication to the patient or their primary care doctor.

The Lesson

As with all errors in medicine, there are opportunities to improve our individual performances as physicians and opportunities to improve the system in which we work. Direct communication with patients at the bedside is important for incidental findings, including a discussion of the possible consequences if the identified issue is not addressed in the appropriate time frame. Discharge papers that include comments about the finding and the recommended follow-up are also helpful. When possible, sending a message to the patient’s PCP can help facilitate the necessary next steps.

There are also measures that health care systems can take in building more robust systems that empower both physicians and patients. Having standard prewritten discharge instructions about incidental findings can be helpful. Institutions that have an ED follow-up nurse or other clinician can help ensure patients do not lose contact with the health system, especially after ED visits that occur in the middle of the night, weekends, or holidays, when communication is often fragmented. Finally, technology-based solutions such as automated image processing and text recognition can identify findings that may have eluded initial screening.

Dr. Funk is a practicing emergency medicine physician in Springfield, Missouri, and owner of Med Mal Reviewer, LLC. He writes about medical malpractice at www.medmalreviewer.com.

Dr. Funk is a practicing emergency medicine physician in Springfield, Missouri, and owner of Med Mal Reviewer, LLC. He writes about medical malpractice at www.medmalreviewer.com.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “A Lack of Communication Let a Cancer Grow, Which Led to a Lawsuit”