A difficult airway is every emergency physician’s worst nightmare. The decision to intubate a patient needs to be coupled with adequate preparation, good communication with nurses and other team members, and a backup plan for possible complications. These situations require rapid decision making under stress. The case below depicts a real-life situation that resulted in a medical malpractice lawsuit. The descriptions and figures shown are the actual evidence used in the lawsuit.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 39 – No 09 – September 2020The Case

A 52-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath. She was brought to the emergency department in a wheelchair by her husband. The triage nurse immediately recognized that she was in severe respiratory distress. Her respirations were noted to be rapid and labored, and she had an audible gurgle. She was assigned a triage Level 1.

There were no available rooms, so she was put in a hallway bed. The physician was immediately at the bedside. He noted that she was cool, clammy, and grossly cyanotic. The patient was able to state that she did not have asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease but did note a history of congestive heart failure. After a very limited history, the patient’s respiratory status declined into complete apnea. The physician made an initial attempt at blind nasal intubation while the nurses started an IV, but he was unsuccessful. A second attempt was made, also with no success. By that time, the nurses had cleared a room and she was brought into the resuscitation bay. The patient’s heart rate declined to 40 bpm on the monitor, a pulse could not be palpated, and chest compressions were started. One milligram of epinephrine was given.

By then, the nurses had established an IV, and 5 mg midazolam (Versed) was given. An oral intubation was attempted without any success. The doctor then elected to place a King Airway device. The patient was ventilated through the King Airway, return of spontaneous circulation was obtained, and her oxygen saturation increased to 97 percent.

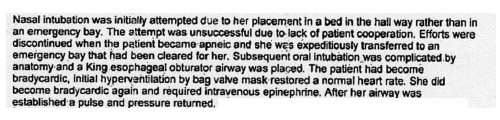

A portion of the doctor’s note describing the events is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Over the next 10 minutes, the patient’s oxygen saturation declined to the mid-80s. She was given lorazepam (Ativan) for sedation and furosemide (Lasix), as the physician suspected fluid overload. The physician also prescribed dexamethasone (Decadron) and diphenhydramine (Benadryl) to reduce airway swelling as well as metoprolol due to the fact that she was hypertensive. Outside medical records were obtained showing that she had a coronary artery bypass graft approximately 18 months earlier.

Obtaining a Transfer

With her oxygen saturation holding in the 80s, the physician began the process to transfer her to a hospital with ICU capabilities. This process was unfortunately fraught with unnecessary delays. An emergency physician (Dr. H) at a regional medical center recommended that she be transferred to an academic center. The academic center was called, took down the patient’s information, and said they would call back, but 30 minutes later there was still no response. The doctor then tried a third hospital, and the cardiologist on-call declined the admission until the emergency physician consulted the patient’s outpatient cardiologist. The outpatient cardiologist worked at the first hospital that had been called, and he ultimately accepted the patient.

The patient departed the emergency department via helicopter with an oxygen saturation of approximately 80 percent. On arrival to the receiving hospital, her oxygen saturation was noted to be 40 percent. The anesthesia team was waiting for the patient at the bedside in the ICU, removed the King airway, and intubated the patient.

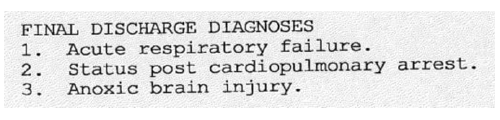

The patient’s status continued to decline. She sadly passed away five days after going into the emergency department, with the final diagnoses shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

The Lawsuit

Figure 3

The patient’s family was understandably upset and contacted an attorney. The subsequent lawsuit is unusual and demonstrates an interesting legal twist emergency physicians should be aware of and understand. The lawsuit alleged an EMTALA violation by Dr. H, the emergency physician at the receiving hospital. He had originally recommended that the patient be transferred to a nearby academic medical center instead, but she ultimately was transferred to his facility after numerous phone calls. In addition to an alleged EMTALA violation, the lawsuit also alleged that he was negligent in his responsibility to the patient.

Dr. H was deposed (see Figure 3). He stated that he did not explicitly decline the transfer but that he was helping the sending physician brainstorm the best arrangement for the transfer.

Ultimately, Dr. H’s attorneys filed for summary judgment. The lawsuit was dismissed because EMTALA allows for legal action against hospitals but not against individual physicians. Further, the defense asserted that Dr. H could not be personally liable for negligence because he did not establish a relationship with the patient solely on the basis of taking a phone call about her possible transfer.

Learning Points

The initial approach to intubation was challenging due to a precipitous arrival to the emergency department and the fact that there were no appropriate rooms available. Without the correct setting and tools, no physician can be successful. Administrators and directors are responsible for putting physicians in a position to succeed. The decision to rapidly proceed with nasal intubation and without rapid sequence intubation (RSI) medications is suspect. Instead, giving bag-valve mask-assisted ventilations while IV access was established and RSI medications were prepared may have temporized the situation and permitted the possibility of a better outcome. That said, moving to a King Airway or supraglottic device shows the physician had a backup plan, which should always be in the forefront of the mind when performing an intubation.

The patient’s transfer proved challenging for the emergency physician. He made numerous calls to several institutions before eventually sending the patient to the first hospital he had called. This prolonged delay did the patient no favors. Physicians working in large medical centers sometimes have difficulty understanding the situation in rural emergency departments. They should keep in mind the challenges of working in a small hospital with limited resources. There have been numerous lawsuits that involved determining precisely when a consulting or receiving physician establishes a patient-doctor relationship. The issue is murky and can vary in different states and by the facts of the case.

Finally, this case involved an alleged EMTALA violation as opposed to standard medical negligence. As demonstrated in this instance, an EMTALA lawsuit brought by a patient against an individual physician is unlikely to succeed. However, this does not mean that doctors are free from punishment for EMTALA violations. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the Office of the Inspector General have enforcement powers that include fines up to $50,000 for physicians.

This case also illustrates the false security of the idea that “you can’t be sued for that.” You can be sued for anything, and even if you are correct, the process is unpleasant. Despite Dr. H’s ultimate vindication, he undoubtedly had numerous meetings with attorneys, spent hours in depositions, and felt a lot of stress over the multiyear course of the lawsuit—and his attorneys certainly did not work for free.

Dr. Funk is a practicing emergency medicine physician in Springfield, Missouri, and owner of Med Mal Reviewer, LLC. He writes about medical malpractice at www.medmalreviewer.com.

Dr. Funk is a practicing emergency medicine physician in Springfield, Missouri, and owner of Med Mal Reviewer, LLC. He writes about medical malpractice at www.medmalreviewer.com.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “A Patient Transfer Leads to a Lawsuit”