Explore This Issue

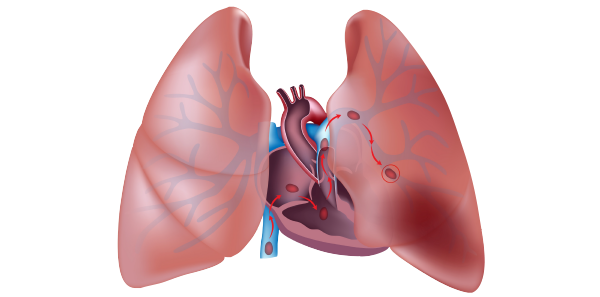

ACEP Now: Vol 38 – No 03 – March 2019Emergency department over-investigation is, perhaps, nowhere more pervasive than in the workup of suspected pulmonary embolism (PE). Data from the EMPEROR Registry in 2011 found that the mortality rate directly attributable to PE was only 1 percent, while the all-cause 30-day mortality rate was 5.4 percent, and mortality from hemorrhage was 0.2 percent.1 Interestingly, 85 percent of deaths occurred in untreated patients while waiting for diagnostic confirmation. It appears from this data that most patients with PE die of comorbidities, such as malignancy, which might have placed the patient at risk for PE, or die from delay in treatment while waiting for imaging confirmation. Much of this decreased mortality may be related to the increase in diagnosis of clinically insignificant subsegmental PEs in the past two decades. Comparison of pooled data from uncontrolled outcome studies shows no increase in PE recurrence or death rates for patients diagnosed with isolated subsegmental PEs who were not anticoagulated compared to those who were.2 In the last 10 years, the incidence of diagnosed PE has doubled, despite no change in mortality, partly due to advances in CT technology and partly due to radiologists overcalling subsegmental PEs due to medico-legal concerns.

The unnecessary testing for PE, and subsequent treatments following diagnosis, may cause harm to patients, result in more follow-up testing from false-positive results, contribute to more anxiety for patients and their families, skyrocket costs, and consume valuable resources. PE costs the United States about $1.5 billion annually, with estimates of more than $30,000 per PE diagnosed.3

To avoid unnecessary radiation and major bleeding complications as a result of anticoagulating patients with false-positive CT pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) results, it’s important to have a rational approach to imaging for PEs, as well as a good approach to shared decision making with our colleagues, radiologists, and patients.

A landmark article published more than 30 years ago in the Canadian Medical Association Journal outlines four principles of diagnostic decision analysis:4

- In the diagnostic context, patients do not have disease, only a probability of disease.

- Diagnostic tests are merely revisions of probabilities.

- Test interpretation should precede test ordering.

- If the revisions in probabilities caused by a diagnostic test do not entail a change in subsequent management, use of the test should be reconsidered.

We tend to overestimate the risk of PE, which leads to overtesting.5 The vast majority of patients who are considered for PE are low-risk according to Wells’ criteria. We order many needless CTs for fear of a PE in low- and no-risk patients. Remember that placing PE in the top three considerations in your differential diagnosis of a patient who presents with chest pain or shortness of breath does not necessarily mean they are at high risk for PE. The PROPER trial out of France, where the prevalence of PE is low, showed that gestalt performed similarly to pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria (PERC) in terms of three-month PE rate, but PERC resulted in an 8 percent decrease in unnecessary CT scanning and a 40-minute decrease in ED stay.6 Other studies have shown that even seasoned physicians have a tendency to overestimate pretest probability in low-risk patients.7 We should all take the time to calculate these validated scores.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Single Page

One Response to “A Rational Approach to Pulmonary Embolism Evaluation”

April 14, 2019

Mark Baker, FACEP, FAMIAThanks for addressing an important topic. I liked the information about the landmark Canadian article. This is what Bayes theorem does. The likelihood of a test being a true positive or a false positive is based on the prior probability of the disease before the test was done. For example,a positive HIV test on a group of IV drug users sharing needles is likely to be a true positive. A positive HIV test on a group of patients with no risk factors at all is much less likely to be a true positive and more may be a false positive. So don’t throw darts at diagnoses… use tests wisely knowing the prior probability of the disease and how the test will change your management.