Explore This Issue

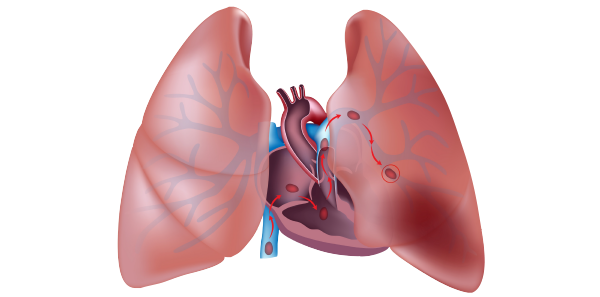

ACEP Now: Vol 38 – No 03 – March 2019Emergency department over-investigation is, perhaps, nowhere more pervasive than in the workup of suspected pulmonary embolism (PE). Data from the EMPEROR Registry in 2011 found that the mortality rate directly attributable to PE was only 1 percent, while the all-cause 30-day mortality rate was 5.4 percent, and mortality from hemorrhage was 0.2 percent.1 Interestingly, 85 percent of deaths occurred in untreated patients while waiting for diagnostic confirmation. It appears from this data that most patients with PE die of comorbidities, such as malignancy, which might have placed the patient at risk for PE, or die from delay in treatment while waiting for imaging confirmation. Much of this decreased mortality may be related to the increase in diagnosis of clinically insignificant subsegmental PEs in the past two decades. Comparison of pooled data from uncontrolled outcome studies shows no increase in PE recurrence or death rates for patients diagnosed with isolated subsegmental PEs who were not anticoagulated compared to those who were.2 In the last 10 years, the incidence of diagnosed PE has doubled, despite no change in mortality, partly due to advances in CT technology and partly due to radiologists overcalling subsegmental PEs due to medico-legal concerns.

The unnecessary testing for PE, and subsequent treatments following diagnosis, may cause harm to patients, result in more follow-up testing from false-positive results, contribute to more anxiety for patients and their families, skyrocket costs, and consume valuable resources. PE costs the United States about $1.5 billion annually, with estimates of more than $30,000 per PE diagnosed.3

To avoid unnecessary radiation and major bleeding complications as a result of anticoagulating patients with false-positive CT pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) results, it’s important to have a rational approach to imaging for PEs, as well as a good approach to shared decision making with our colleagues, radiologists, and patients.

A landmark article published more than 30 years ago in the Canadian Medical Association Journal outlines four principles of diagnostic decision analysis:4

- In the diagnostic context, patients do not have disease, only a probability of disease.

- Diagnostic tests are merely revisions of probabilities.

- Test interpretation should precede test ordering.

- If the revisions in probabilities caused by a diagnostic test do not entail a change in subsequent management, use of the test should be reconsidered.

We tend to overestimate the risk of PE, which leads to overtesting.5 The vast majority of patients who are considered for PE are low-risk according to Wells’ criteria. We order many needless CTs for fear of a PE in low- and no-risk patients. Remember that placing PE in the top three considerations in your differential diagnosis of a patient who presents with chest pain or shortness of breath does not necessarily mean they are at high risk for PE. The PROPER trial out of France, where the prevalence of PE is low, showed that gestalt performed similarly to pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria (PERC) in terms of three-month PE rate, but PERC resulted in an 8 percent decrease in unnecessary CT scanning and a 40-minute decrease in ED stay.6 Other studies have shown that even seasoned physicians have a tendency to overestimate pretest probability in low-risk patients.7 We should all take the time to calculate these validated scores.

Imaging Options

Although CTPA is generally considered the gold standard for diagnosing PE, it is far from perfect, and ventilation/perfusion single-photon emission CT (V/Q SPECT) may have better test characteristics. CTPA is prone to over-diagnosing clinically irrelevant emboli in low-risk patients.8 Furthermore, although its sensitivity approaches 100 percent for clinically relevant PEs, those patients at high risk for PE, based on a Wells’ score >6, who have a negative CTPA should be counseled that up to 5 percent of high-risk patients may develop a PE within a few months of a negative CTPA.9,10

Clot burden and clot location on CTPA have not been shown to accurately predict outcome or even symptoms. The clinical context is much more important, and markers such as hypotension and hypoxia are far better outcome predictors.11

V/Q SPECT has been shown to have superior accuracy compared to traditional V/Q and has similar sensitivity compared to CTPA for pulmonary embolism.12,13 V/Q SPECT eliminates intermediate probability scans and is reported dichotomously as positive or negative for PE. This avoids the ambiguity of results seen with traditional V/Q scan interpretation. Robust data are pending regarding its diagnostic utility compared to CTPA. However, the current evidence suggests that it may be superior with a lower dose of radiation to breast tissue.13 Consider V/Q SPECT not only in otherwise healthy young patients with a normal chest X-ray and those with CT contrast allergy but also in patients with existing lung disease.

Treatment Decisions

Is there any evidence for clinical benefit in treating subsegmental PE found on CTPA? An observational study by Goy et al in 2015 reviewed 2,213 patients with a diagnosis of subsegmental PE and showed that whether or not anticoagulation was given, there were no recurrent PEs. However, 5 percent of anticoagulated patients developed life-threatening bleeding.14 Other studies have yielded similar results.15

Shared decision making plays an important role for patients suspected of PE. Consider the patient’s bleeding risk (HAS-BLED score) and discuss potential treatment options. The 2018 ACEP Clinical Policy on Acute Venous Thromboembolic Disease gives withholding anticoagulation in patients with subsegmental PE a Level C recommendation and states: “Given the lack of evidence, anticoagulation treatment decisions for patients with subsegmental PE without associated [deep vein thrombosis] should be guided by individual patient risk profiles and preferences [Consensus recommendation].”16

Nonetheless, I recommend starting anticoagulants for subsegmental PE in the emergency department with a clear explanation that anticoagulants may (and probably should) be stopped in follow-up. While the risk of major bleeding with a full course of anticoagulation is significant, the risk of bleeding from a few doses of anticoagulant is very low. Thus, starting treatment for subsegmental PE in the emergency department and referring the patient for timely (within a few days) follow-up in a thrombosis or internal medicine clinic is a reasonable option. Consultants may risk-stratify low-risk patients with serial lower-extremity Doppler ultrasound to direct ongoing therapy.

Big-Picture Solutions to Over-Investigating

Some potential solutions to over-investigating include malpractice reform, more time spent talking to patients, and a change in the system of financial rewards for ordering tests. For PE workup in particular, departmental decision support systems have been shown to reduce imaging rates and increase diagnostic yield.17

So next time you’re about to pull the trigger on ordering a CTPA for suspected PE based on gestalt, instead take the time to use your evidence-based departmental decision support system that utilizes diagnostic decision tools such as Geneva score, Wells’ score, D-dimer and PERC rule. If your patient is young or has a contrast allergy, consider a V/Q SPECT as a potentially more accurate test for PE that may result in fewer false positives with less radiation than CTPA.

Special thanks to Dr. Eddy Lang and Dr. Kerstin de Wit for their expert contributions to the EM Cases podcast on which this article was based.

References

- Pollack CV, Schreiber D, Goldhaber SZ, et al. Clinical characteristics, management, and outcomes of patients diagnosed with acute pulmonary embolism in the emergency department: initial report of EMPEROR (Multicenter Emergency Medicine Pulmonary Embolism in the Real World Registry). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(6):700-706.

- Bariteau A, Stewart LK, Emmett TW, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes of patients with subsegmental pulmonary embolism with and without anticoagulation treatment. Acad Emerg Med. 2018;25(7):828-835.

- MacDougall DA, Feliu AL, Boccuzzi SJ, et al. Economic burden of deep-vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and post-thrombotic syndrome. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63(20 suppl 6):S5-S15.

- Schechter MT, Sheps SB. Diagnostic testing revisited: pathways through uncertainty. Can Med Assoc J. 1985;132(7):755-760.

- Penaloza A, Verschuren F, Meyer G, et al. Comparison of the unstructured clinician gestalt, the wells score, and the revised Geneva score to estimate pretest probability for suspected pulmonary embolism. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(2):117-124.e2.

- Freund Y, Cachanado M, Aubry A, et al. Effect of the pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria on subsequent thromboembolic events among low-risk emergency department patients: the PROPER randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319(6):559-566.

- Kline JA, Stubblefield WB. Clinician gestalt estimate of pretest probability for acute coronary syndrome and pulmonary embolism in patients with chest pain and dyspnea. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;63(3):275-280.

- van Belle A, Büller HR, Huisman MV, et al. Effectiveness of managing suspected pulmonary embolism using an algorithm combining clinical probability, D-dimer testing, and computed tomography. JAMA. 2006;295(2):172-179.

- van der Hulle T, van Es N, den Exter PL, et al. Is a normal computed tomography pulmonary angiography safe to rule out acute pulmonary embolism in patients with a likely clinical probability? A patient-level meta-analysis. Thromb Haemost. 2017;117(8):1622-1629.

- Belzile D, Jacquet S, Bertoletti L, et al. Outcomes following a negative computed tomography pulmonary angiography according to pulmonary embolism prevalence: a meta-analysis of the management outcome studies. J Thromb Haemost. 2018;16(6):1107-1120.

- den Exter PL, van Es J, Klok FA, et al. Risk profile and clinical outcome of symptomatic subsegmental acute pulmonary embolism. Blood. 2013;122(7):1144-1149.

- Gutte H, Mortensen J, Jensen CV, et al. Comparison of V/Q SPECT and planar V/Q lung scintigraphy in diagnosing acute pulmonary embolism. Nucl Med Commun. 2010;31(1):82-86.

- Bhatia KD, Ambati C, Dhaliwal R, et al. SPECT-CT/VQ versus CTPA for diagnosing pulmonary embolus and other lung pathology: pre-existing lung disease should not be a contraindication. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2016;60(4):492-497.

- Goy J, Lee J, Levine O, et al. Sub-segmental pulmonary embolism in three academic teaching hospitals: a review of management and outcomes. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13(2):214-218.

- Yoo HH, Queluz TH, El Dib R. Anticoagulant treatment for subsegmental pulmonary embolism. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(4):CD010222.

- ACEP Clinical Policies Subcommittee (Writing Committee) on Thromboembolic Disease. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients presenting to the emergency department with suspected acute venous thromboembolic disease. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;71(5):e59-109.

- Deblois S, Chartrand-Lefebvre C, Toporowicz K, et al. Interventions to reduce the overuse of imaging for pulmonary embolism: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(1):52-61.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

One Response to “A Rational Approach to Pulmonary Embolism Evaluation”

April 14, 2019

Mark Baker, FACEP, FAMIAThanks for addressing an important topic. I liked the information about the landmark Canadian article. This is what Bayes theorem does. The likelihood of a test being a true positive or a false positive is based on the prior probability of the disease before the test was done. For example,a positive HIV test on a group of IV drug users sharing needles is likely to be a true positive. A positive HIV test on a group of patients with no risk factors at all is much less likely to be a true positive and more may be a false positive. So don’t throw darts at diagnoses… use tests wisely knowing the prior probability of the disease and how the test will change your management.