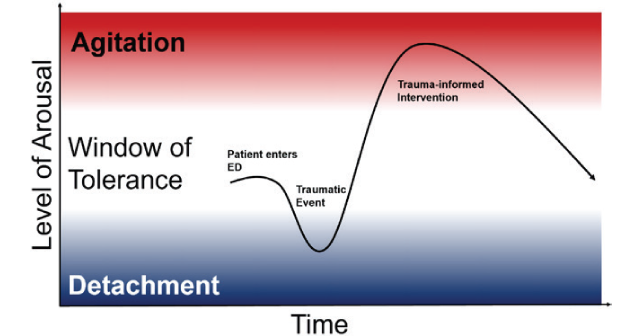

Physicians, nurses, and staff in emergency departments (EDs) across the country have encountered workplace violence for years. According to federal labor statistics, the prevalence of workplace violence in health care is increasing (see Figure 1). While staff exposure to this violence varies, literature shows nurses are most frequently exposed, with up to 90 percent having experienced workplace violence in their ED careers.1,2 In a 2018 study by ACEP, nearly half of emergency physicians polled reported a physical assault while at work.3 Solutions focused on security or law enforcement responses have not improved these statistics because they fail to address the root causes of workplace violence. For the safety of staff as well as patients, interventions that interrupt escalations before they blossom into violence deserve further study.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 42 – No 11 – November 2023

FIGURE 1: Number of nonfatal workplace violence injuries and illnesses with days away from work, 2011-18. (Click to enlarge.)

The Story in Data

Violence experienced in the ED is often due to agitated, confused, or delirious patients. A study done at the University of Kansas found that approximately 10 percent of the ED volume at a local county hospital was attributed to some type of behavioral emergency and that approximately one in eight ED visits in the U.S are caused by a behavioral crisis.4 As with other daily challenges in the practice of emergency medicine, EDs deserve a range of nuanced, effective tools that can be tailored to particular patients and scenarios. Unfortunately, the science has thus far lagged behind the ballooning behavioral need.

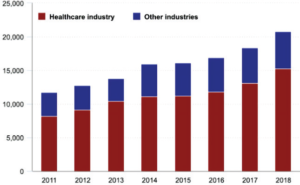

Managing and caring for aggressive patients may involve calling for security or physical and chemical restraints, but these interventions are temporary and have potential to further harm patients physically and mentally.5 Hospitals commonly activate a “code” in response to agitated patients, alerting security personnel to the location of that patient. The difficulty with this approach is that these officers often lack the skills and context needed to de-escalate complex behavioral crises. A study from Australia sought to understand security personnel’s experiences responding to agitated patients in the ED: they frequently felt that they lacked information, coordination, and communication when responding with urgent assistance.6 While the presence of officers can be comforting to staff, it can also be triggering to patients. Security and law enforcement officers can further amplify a patient’s stress response. As additional stress reactions are activated, the window of tolerance for a patient experiencing a traumatic response narrows, increasing the likelihood of escalation.7

This decontextualized response is also challenging for responders. In one ED in the San Francisco area, a law enforcement officer staffed there said they would appreciate additional support for de-escalating patients. From the law enforcement perspective, hospital policies regarding behavioral codes were “vague” and the same patients are often seen multiple times with similar behavioral crises, he noted in an interview. Both security and health care teams assisting during these crises may benefit from a re-framing of the response to mentally vulnerable patients during times of aggression.

When a patient first enters the ED, they may be within their window of tolerance of stimuli and interventions, (see Figure 2) but a triggering event may cause an initial detached state (numb, quiet, dissociated) to a hyper-aroused agitated state (yelling, getting out of bed, throwing objects). Trauma-informed interventions deployed by BERTs use de-escalation techniques to move the patient from the hyper-aroused state back into the window of tolerance so that they can effectively engage in their care.

A Call for Change: BERTs

Just as rapid response teams have been created to attend urgently to medically decompensating patients in the hospital, Behavioral Emergency Response Teams (BERTs) have been created to rapidly identify and tend to a patient whose behavior is escalating. Evidence from inpatient wards, outpatient facilities, and addiction treatment centers has demonstrated that BERTs are an effective de-escalation solution in a variety of care contexts.

A 2019 literature review summarized seven studies describing the creation and implementation of BERT teams. Led by psychiatric-trained nurses, teams responding to behavioral codes used a variety of de-escalation methods including non-confrontational communication, moving the patient to a less stimulating environment, and adjusting medications as necessary. Across clinical contexts, BERT teams reduced the activity of security personnel, restraint and seclusion use, and staff injuries.5 A University of Kansas study found that their BERT structure fosters “a collaborative team within the ED and provides a model of humane care.”4

Conclusion

More implementation studies of this emerging behavioral solution in resource-limited emergency settings are needed. Our group from Highland Hospital has set out to understand the impact on workplace violence and patient safety of initiating a BERT in a busy, county hospital ED. “The workplace violence data in emergency departments are staggering, and it can feel defeating, especially when we and our colleagues experience it firsthand,” explains Dr. Nikita Joshi, faculty lead for efforts to reduce workplace violence in the county health system. “But BERT is an important initiative to proactively address it–in a way that is patient centric, trauma informed, and most of all, empathic toward the patient and the clinician.” The well-being of our patients, staff, and ourselves depends on finding tailored and effective solutions and dissemination of these best practices.

Dr. Santamaria is a current second year medical student at A.T Still University School of Osteopathic Medicine, in Mesa, Ariz.

Dr. Santamaria is a current second year medical student at A.T Still University School of Osteopathic Medicine, in Mesa, Ariz.

Dr. Ashworth is a current emergency medicine resident at Highland Hospital, in Oakland, Calif.

Dr. Ashworth is a current emergency medicine resident at Highland Hospital, in Oakland, Calif.

Dr. Dellinger is a current emergency medicine resident at Highland Hospital, in Oakland, Calif.

Dr. Dellinger is a current emergency medicine resident at Highland Hospital, in Oakland, Calif.

Dr. Heeney is a current emergency medicine resident at Highland Hospital, in Oakland, Calif.

Dr. Heeney is a current emergency medicine resident at Highland Hospital, in Oakland, Calif.

Dr. Lee is a second-year resident in emergency medicine at Highland Hospital in Oakland, Calif.

Dr. Lee is a second-year resident in emergency medicine at Highland Hospital in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Workplace Violence in Healthcare, 2018. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics website. Published 2018. Accessed October 10, 2023.

- Lee H, Yun H, Choi M, Kim H. Predicting workplace violence in the emergency department based on electronic health record data. J Emerg Nurs. 2023;(3):415-424.

- Roppolo LP, Morris DW, Khan F, et al. Improving the management of acutely agitated patients in the emergency department through implementation of Project BETA (Best Practices in the Evaluation and Treatment of Agitation). J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2020;(5):898-907.

- Schulz JA, Ramaswamy M, Collie-Akers V, et al. Understanding the impact of an integrated crisis team: A qualitative study of emergency department staff. Community Ment Health J. 2021;(7):1278-1287.

- Choi KR, Omery AK, Watkins AM. An integrative literature review of psychiatric rapid response teams and their implementation for de-escalating behavioral crises in nonpsychiatric hospital settings. J Nurs Admin. 2019;(6):297-302.

- Davids J, Murphy M, Moore N, et al. Exploring staff experiences: A case for redesigning the response to aggression and violence in the emergency department. J Emerg Nurs. 2021:57:101017.

- Gill LG. Understanding and working with the window of tolerance. Attachment And Trauma Treatment Centre For Healing website. Published November 25, 2017. Accessed October 10, 2023.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “A Safety Solution for Emergency Department Staff and Patients”